Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Law &

Order: Pirate Edition

by Cindy Vallar

Insidious

and pernicious. These two words can be applied to

pirates throughout history. One of the earliest

attempts to eradicate sea raiders happens in 694 BC

when Sennacherib, the king of

Assyria, tries to do so. The best-known offensive

against them occurs in 67 BC, when the Roman Senate

sanctions Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey

the Great) to gather 270 vessels and sweep across

the Mediterranean to wipe out pirates and their

bases. The milestone in these attacks takes place on

Anatolia’s coast, when Pompeius and his men slay

10,000 pirates and seize 400 ships, but they also

help the survivors transform themselves into

farmers. In between these two events, Alexander the Great implements

his own suppression endeavors in 330 BC. He just

doesn’t expect to find a sea raider with enough

gumption to stand up to him.

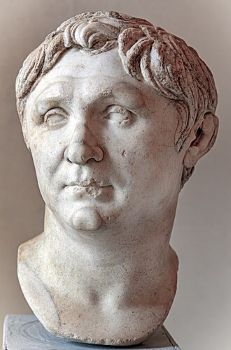

Sennacherib (Cast

of a rock relief from the foot of Cudi Dağı,

near Cizre and now exhibited in Landshut,

Germany)

[Source: Timo Roller, 2015 at Wikimedia Commons]

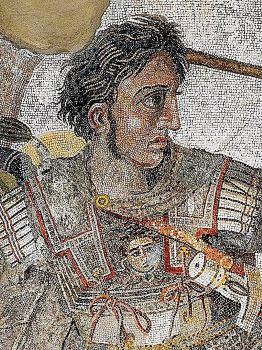

Bust of Pompeius the Great

(Museo archeologico nazionale in Venice) by

unknown artist of AD first century

[Source: Didier Descouens, 2023 at Wikimedia Commons]

Section of mosaic depicting

Alexander the Great at the House of the Faun

on Pompeii

[Source: Unknown artist, circa 100 BC, Wikimedia Commons]

In De civitate Dei contra paganos (The

City of God), Saint Augustine recounts an

interview between Alexander the Great and a captured

pirate named Diomedes. The Macedonian king asks why

Diomedes dares to rob people at sea. Since execution

awaits the pirate, he has nothing to lose and poses

a cheeky question instead: What gives Alexander the

right to invade and conquer other lands? Diomedes

sees no difference between what they both do.

Alexander, who has wealth and power, does what he

wants and gets away with “pirating” other countries.

Whereas he, lowly Diomedes, is deemed a sea robber

because he chooses to do the same thing on a much

smaller scale. Seeing the truth, or wisdom, in what

Diomedes says, Alexander offers the pirate a pardon

so he can begin life anew.

Excusing

a crime without exacting a penalty might seem like

an unusual way to suppress piracy, but sovereigns

around the world offered such pardons multiple times

throughout history. King George I of England, for

example, signed a proclamation offering pirates an Act of Grace during the most

prolific period of marauding in the early eighteenth

century. His predecessor, James I extended pardons to

pirates in Ireland in 1609; two years later, he

agreed to pardon other pirates, such as Peter Easton, but corruption

within the Emerald Isle eventually led James’s Privy

Council to add a stipulation. Any pirate hopeful of

a pardon must “repair to some port in England” to

obtain one. (Appleby, Affairs, 81) Excusing

a crime without exacting a penalty might seem like

an unusual way to suppress piracy, but sovereigns

around the world offered such pardons multiple times

throughout history. King George I of England, for

example, signed a proclamation offering pirates an Act of Grace during the most

prolific period of marauding in the early eighteenth

century. His predecessor, James I extended pardons to

pirates in Ireland in 1609; two years later, he

agreed to pardon other pirates, such as Peter Easton, but corruption

within the Emerald Isle eventually led James’s Privy

Council to add a stipulation. Any pirate hopeful of

a pardon must “repair to some port in England” to

obtain one. (Appleby, Affairs, 81)

Pardons were often merely one tool in the

authorities’ arsenal. If a pirate chose to ignore

the pardon and resume plundering, he would be hunted

down, prosecuted, and punished. This was what

happened to Charles Vane, who sneered at King

George’s pardon, and Calico Jack Rackham, who signed

the pardon but returned to his old ways.

When Woodes Rogers assumed the

governorship of the Bahamas in 1718, part of his

mission was to eradicate piracy. The islands were

both a haven and a staging ground for the

scoundrels, but not everyone was amenable to

returning to society and obeying the rules and

regulations that identified what a person could or

could not. Vane warned Rogers that he would only

surrender on his terms:

That you

will suffer us to dispose of all our Goods now

in our Possession. Likewise, to act as we think

fit with every Thing belonging to us, as his

Majesty’s Act of Grace specifies. (Defoe,

142)

Woodes

had no intention of giving the pirate the upper

hand, and after creating some mischief, Vane and his

men fled the Bahamas. Various pirate hunters, such

as Colonel William Rhett of South

Carolina who captured Stede Bonnet, attempted to

track down Vane and bring him in, but none

succeeded. His initial comeuppance came at the hands

of his fellow pirates, who ousted him as captain and

sent him off in a boat with some loyal followers.

Mother Nature delivered her own justice when a

hurricane destroyed this vessel. Only two men, Vane

being one of them, survived the ordeal. Rescue

seemed close at hand when a ship happened upon the

uninhabited island, but her captain recognized Vane

and, knowing his untrustworthy nature, sailed away.

Sometime later, this same captain came aboard

another ship and recognized one of the seamen. Vane

was clapped in irons and taken to Port Royal,

Jamaica, where he was hanged in 1721.1

His corpse was gibbeted on Gun Cay as a warning to

others. Woodes

had no intention of giving the pirate the upper

hand, and after creating some mischief, Vane and his

men fled the Bahamas. Various pirate hunters, such

as Colonel William Rhett of South

Carolina who captured Stede Bonnet, attempted to

track down Vane and bring him in, but none

succeeded. His initial comeuppance came at the hands

of his fellow pirates, who ousted him as captain and

sent him off in a boat with some loyal followers.

Mother Nature delivered her own justice when a

hurricane destroyed this vessel. Only two men, Vane

being one of them, survived the ordeal. Rescue

seemed close at hand when a ship happened upon the

uninhabited island, but her captain recognized Vane

and, knowing his untrustworthy nature, sailed away.

Sometime later, this same captain came aboard

another ship and recognized one of the seamen. Vane

was clapped in irons and taken to Port Royal,

Jamaica, where he was hanged in 1721.1

His corpse was gibbeted on Gun Cay as a warning to

others.

Once

Vane’s quartermaster, Rackham opted to take

advantage of the king’s amnesty in 1719. Whether

pillaging proved too tempting or difficulties

concerning Anne Bonny’s marital status forced Jack

to rethink his decision, he returned to marauding.

This resumption made him fair game for pirate

hunters, and he was captured in November 1720 by

Captain Jonathan Barnett. Found guilty at his trial

in Port Royal, he, too, danced the hempen jig before

being placed on display at Deadman’s Cay (now

Rackham’s Cay). Once

Vane’s quartermaster, Rackham opted to take

advantage of the king’s amnesty in 1719. Whether

pillaging proved too tempting or difficulties

concerning Anne Bonny’s marital status forced Jack

to rethink his decision, he returned to marauding.

This resumption made him fair game for pirate

hunters, and he was captured in November 1720 by

Captain Jonathan Barnett. Found guilty at his trial

in Port Royal, he, too, danced the hempen jig before

being placed on display at Deadman’s Cay (now

Rackham’s Cay).

Unlike the codes by which pirates operated, which

applied equally to each and every pirate within a

crew, implementation of land-based laws was

sometimes dependent on one’s station in life. The Killigrews of Cornwall had

deep ties to the ruling Tudors, and their misdeeds

were often overlooked or treated more like slaps on

the wrist. Until some Spaniards decided the

Killigrews had gone too far and took their case to Elizabeth I. An international

incident was not what the queen wanted, so Lady Mary

Killigrew and two of her servants were arrested.

Whereas Lady Mary was pardoned, her servants were

hanged.

When Westerners came to Asian waters, they brought

with them their concept of what constituted piracy.

This notion was alien to Asians because the word

“pirate” was unknown, and their deeds were not seen

in the same way that they were in Europe. Chinese,

for example, had a number of words that pertained to

those who raided at sea – haizei, haidao,

haikou, and yangfei, for example –

but none of these were specifically “pirates” as

Westerners thought of these plunderers. Although sea

people did rob and blackmail victims, it was common

for a sea merchant and a pirate to be one and the

same, depending on circumstances at home. One reason

for this was that at times sea bans (haijan)

were decreed, which essentially shut down maritime

trade, especially between China and other countries.

Imperial thinking was that without such commerce,

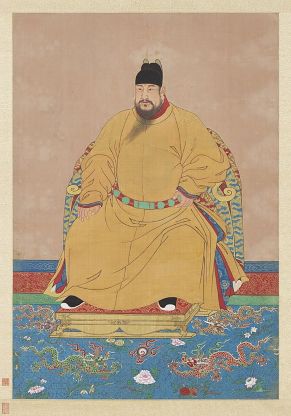

piracy would end, except Emperor Zhu Gaochi (also known

as the Hongxi Emperor) found out differently after

imposing one such ban in the early 1400s. No trade

actually prompted more smuggling and piracy. This

gave rise to men like Zheng Zhilong, a powerful and

successful merchant, pirate, smuggler, and sea lord

of the seventeenth century. He was later executed

but not for his piracy. He was beheaded because his

son refused to surrender to the Qing officials who

ruled China.

Emperor Zhu Gaochi, also known

as the Hongxi Emperor, by unknown artist of

the Ming Dynasty

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Zheng Zhilong in Taiwain Waiji,

1699 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

During the Qing Dynasty, pirates (zheng dao)

broke the law by raiding ships and coastal villages.

After such violent attacks, these gang members

shared whatever illicit booty they had acquired. The

punishment for those convicted of piracy was zhan

lijue xiaoshi (beheading of the pirate and

displaying of his head, much like Westerners

displayed the corpses of executed pirate captains).

So many pirates plagued China’s waters in 1796, that

the emperor gave authorities permission to

immediately execute convicted pirates rather than

wait for his permission. Some severed heads were

sent to locales where the crimes had been committed

and displayed on pikes or in cages for all to see.

In instances where the crimes were particularly

brutal, lingchi (death

by 1,000 cuts) was deemed more appropriate.

The

criminal is fastened to a rough cross, and the

executioner, armed with a sharp knife, begins by

grasping handfuls from the fleshy parts of the

body, such as the thighs and the breasts, and

slicing them off. After this he removes the

joints and the excrescences of the body one by

one – the nose and ears, fingers and toes. Then

the limbs are cut off piecemeal at the wrists

and the ankles, the elbows and knees, the

shoulders and hips. Finally, the victim is

stabbed to the heart and his head cut off.

(Norman, 225)

According to Qing law, a

pirate plundered vessels at sea or on a river or

employed a boat to go ashore to pillage villages or

other places where people lived. Rather than judge

prisoners for the single crime of piracy, the

authorities viewed each act as a separate offense.

This meant the charges against captured pirates on a

single raid might include abduction, extortion,

homicide, theft, and violence (such as rape or

wounding).

Governor-General Bai Ling believed that “without

rice and gunpowder there would be no pirates.”

(Antony, Like, 129) In 1809, he instituted a

variety of policies to clamp down on piracy. One

required vessels carrying rice to be armed and

protected by soldiers; they also had to sail in

convoys of eight to ten boats. Some rice was

transported overland instead of by water. Detailed

records of gunpowder needed to be kept, and those

who worked with the explosive were kept under close

watch. The pirates’ reactions were not what Bai Ling

expected. Instead, they turned violent and for over

two months, navigated inland water routes, pillaging

and kidnapping. When General Xu Tinggui put in at

Weijiamen in July, the pirates staged an ambush.

More than 1,000 soldiers were slain, including

General Xu. Seeing the writing on the wall, Bai Ling

rethought his policies and decided it was better to

pacify the pirates than rile them. His offers of

pardon resulted in more than 1,500 ceasing to live a

life of pillaging and violence. Among them were Zheng Yi Sao and Zhang Bao;

with their surrenders, the great pirate

confederation ceased to exist.

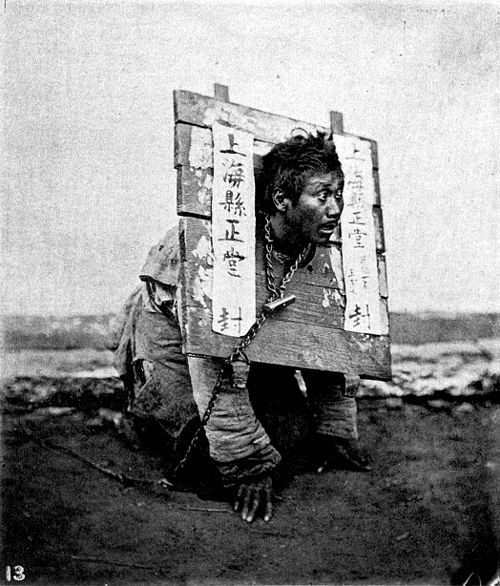

Regardless

of time or place, authorities ultimately understood

that suppressing piracy wasn’t as simple as just

getting rid of pirates. These violators of the law

did not work in a void; they had help. To fully

succeed in eradicating piracy, those who assisted

the pirates had to be dealt with as well. During the

Qing dynasty, Chinese authorities in coastal

communities referred to collaborators who supplied

goods and services to the pirates as jianmin (wicked

people) and lanzai (worthless fellows).

Thousands of these abettors were arrested and tried

between 1780 and 1810. Those found guilty either had

to wear a cangue for a time or

suffer death, depending on just how much this person

helped the pirates.2 Regardless

of time or place, authorities ultimately understood

that suppressing piracy wasn’t as simple as just

getting rid of pirates. These violators of the law

did not work in a void; they had help. To fully

succeed in eradicating piracy, those who assisted

the pirates had to be dealt with as well. During the

Qing dynasty, Chinese authorities in coastal

communities referred to collaborators who supplied

goods and services to the pirates as jianmin (wicked

people) and lanzai (worthless fellows).

Thousands of these abettors were arrested and tried

between 1780 and 1810. Those found guilty either had

to wear a cangue for a time or

suffer death, depending on just how much this person

helped the pirates.2

During the uptick in piracy after 1780, officials

imposed stricter penalties. Yang Yawo was arrested

as an abettor in 1789, but Governor-General Jiqing

didn’t think wearing the cangue was a harsh enough

penalty to make him cease and desist once the device

was removed. Instead, Yang spent three years in

prison, forced to do hard labor. He also received

100 lashes from a bamboo stick. Once he endured

these punishments, the authorities inflicted one

more to guarantee that he never again reverted to

his old ways: relocation further inland. Twenty

years later, Xiao Shique received a similar fate

after being nabbed for selling watermelon to

pirates; his ultimate destination was remote

northeast China near the borders of what is today

known as Inner Mongolia and Russia. At least, these

men survived. Fisherman Yang Pinfu wasn’t so lucky.

Nabbed for selling rice to pirates three separate

times, he literally lost his head.

Mitigating circumstances, such as being forced to

assist pirates, were irrelevant. As far as the

government was concerned, only those who spent their

entire captivity locked away below decks were

released without punishment if rescued. The

remaining captives (beilu zhe) suffered

various forms of punishment.

In the provinces of Fujian and Guangdong, 9,600

people were arrested for piracy, but only 2,803 of

these were actual pirates. Of the remaining 6,797

detainees, all of whom were kidnappees, just 26%

were eventually released without penalty.

Twenty-eight percent had been forced to take part in

raids, which made them accomplices. Pirates

compelled the remaining 46% to do menial tasks. One

such victim was Chen Kaifa, who had been taken by

Zheng Qi. Initially, Chen was assigned menial tasks,

but Zheng decided Chen should act as a lookout (bafeng)

and then he had to help stow the plunder aboard

Zheng’s junk. One time only. Once was enough; in the

eyes of the authorities, the victim was now an

accessory, and he was sentenced to die.

While not considered as guilty as victims like Chen,

even those who brewed tea, hauled on ropes, or

helped to weigh anchor had to be punished. They

received sentences of three years forced labor and

100 whacks with a bamboo rod.

Think such punishments too harsh? Remember the

opening scene of Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End. A line

of shackled men, women, and children shuffle towards

the gallows at Port Royal. Each is to be hanged for

abetting piracy. Yes, it is dramatic license, but

Hollywood merely depicts on a grand scale what

eighteenth-century English law decrees. Even an

accomplice is deemed a pirate and is subject to the

same punishment – dancing the hempen jig.

Notes:

1. Although Great Britain

abolished the death penalty in 1965 for those

convicted of murder, people found guilty of piracy

were still eligible for death until 1998.

2. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary

defines the cangue as “a large, flat, square or

rectangular device that was formerly used in some

Asian countries like a portable pillory for

confining the neck and sometimes also the hands as

punishment.” The word “cangue” is French and derives

from the Portuguese word meaning “yoke.” Cangue is

pronounced “kan-gay.”

Resources (The list is so

extensive that I have placed it on a separate page.)

Copyright ©2025 Cindy

Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |