Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

What Is a

Pirate?

Law & Order: Pirate Edition

by Cindy Vallar

Around 1300, a “new” word entered written English:

pirate. It referred to “a sea-robber, sea-plunderer,

one who without authority and by violence seizes or

interferes with the ship or property of another on

the sea,” according to Etymonline. Earlier words did

exist, depending on the language. Speakers of Old

English (fifth to eleventh centuries) used sæsceaða,

which meant “sea-scather,” while users of Medieval

Latin referred to these marauders as pirata (a

term that applied to a sailor, corsair, or a sea

robber).

Ancient Greeks and Romans used words similar to

“pirate.” Although we can recognize the similarity

between their words and our word, the definition

wasn’t quite the same. Why? Because of context.

“[T]he words peirato and pirata both

connot[ed] political legitimacy or belligerency” in

Ancient Greece and Rome. For example, “the former

being those included under the Roman

hegemony, and the latter being those who lived a way

of life outside Roman hegemony, and

therefore illegitimate.” (Young, 7) In other words,

if you lived by the rules of the Romans, you were a

legal pirate. If you did not, your pirating was

illegal.

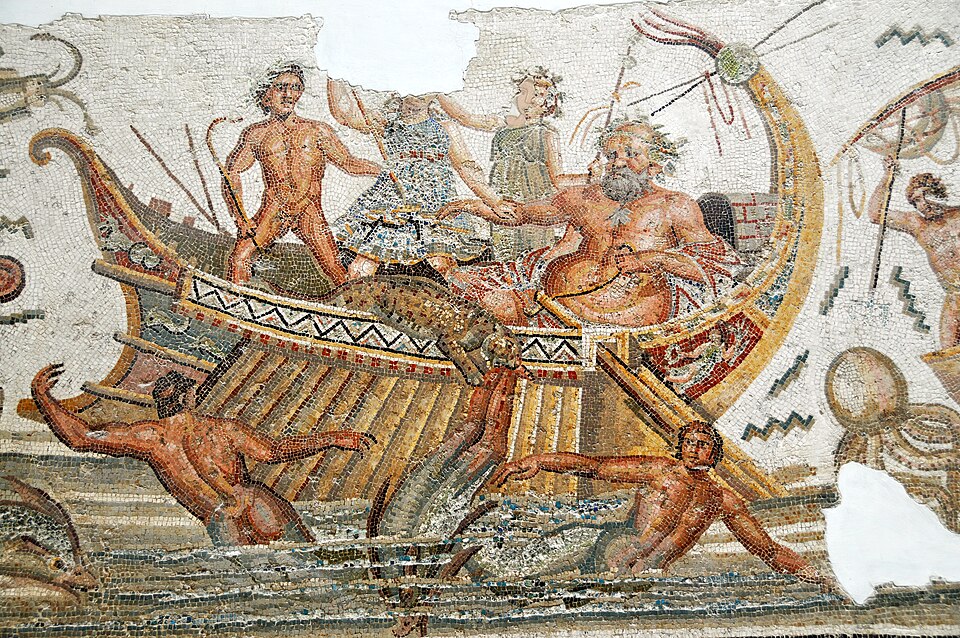

Dionysus (panther)

scattering the pirates, who are transformed into

dolphins

Dionysus (panther)

scattering the pirates, who are transformed into

dolphins

North African Roman mosaic, Bardo National

Museum, Tunisia, photographed by Dennis G.

Jarvis, 2012

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

There was

never a time when piracy was not practiced, nor

may it cease so long as the nature of mankind

remains the same. (Dolin, xxvi)

Although written sometime

between circa AD 150 and 235, his words proved

prophetic. Piracy, no matter the time period, was a

problem that required the intervention of law and

order. By the time the renowned jurist Sir Edward Coke lived in the

late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries,

pirates had gone from simple thieves who plied their

craft at sea to hostis humani generis (enemy

of mankind), a term first associated with pirates by

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 –

43 BC).

.jpg)

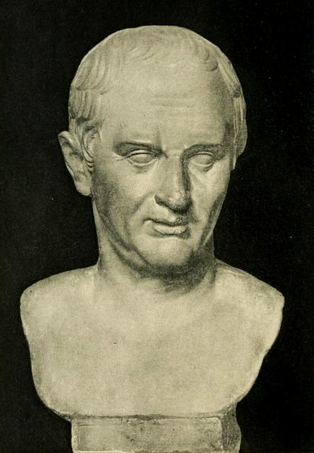

Marble bust of Marcus Tullius

Cicero at age 60 by unknown sculptor

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Frederick II and his falcon from his book De

arte venandi cum avibus (The

Art of Hunting with Birds),

1240s, artist unknown (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Edward III wearing Order of the Garter

miniature from illuminated manuscript Bruges

Garter Book by William Bruges,

circa 1430s (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

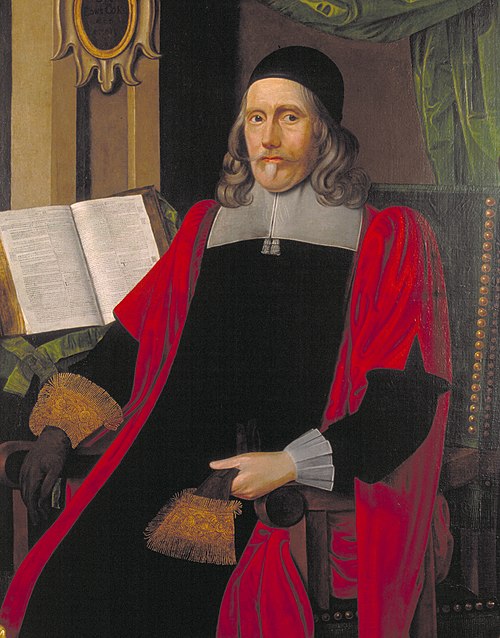

Sir Edward Coke, Chief Justice of the King's

Bench, portrait by Gilbert Jackson, 1615, in

Guildhall Art Gallery (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

One of the earliest laws against piracy was passed

by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in 1220. It

likened pirates to “enemies of Christendom.” (Barbary,

21) Pirates had become such a problem for the

Genoese that they established the Office of Pirates

in 1301, to pay recompense to foreign merchants who

fell victim to pirates from the city. Before the

middle of the fourteenth century, England labeled

piracy as a crime of common law and such criminals

were prosecuted in the assizes. Instead of rendering

verdicts according to the facts in the case, the

juries saw the accused as kindred spirits because

they were peers. Thus, many trials ended in

acquittals for the defendants. During Edward III’s reign, this

happened so often that he proclaimed piracy a form

of treason, and as such, would henceforth be tried

in a court of Admiralty. A schism erupted between

the crown and the assizes, and jurisdiction remained

an issue until Henry VIII’s reign (1509-1547).

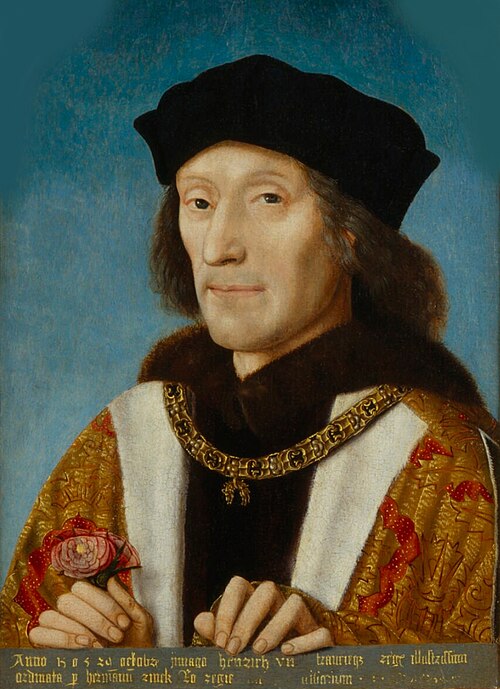

During

the reign of his father (Henry VII, 1584-1509),

plundering at sea had gotten way out of hand.

“[D]ivers and manifold spoliations and robberies be

daily had, committed, and done upon the sea”; the

victims, often his allies, complained persistently.

(Tudor, 25) The offenders even had the gall

to sell the ill-gotten wares in English ports

“contrary to the laws and statutes of this land, in

violation and in breach of the foresaid leagues,

confederations, and amities, and in grievous

contempt of our said sovereign lord.” (Tudor,

25) Therefore, King Henry issued a proclamation

“Ordering Punishment of Piracy against England’s

Allies” on 17 November 1490. During

the reign of his father (Henry VII, 1584-1509),

plundering at sea had gotten way out of hand.

“[D]ivers and manifold spoliations and robberies be

daily had, committed, and done upon the sea”; the

victims, often his allies, complained persistently.

(Tudor, 25) The offenders even had the gall

to sell the ill-gotten wares in English ports

“contrary to the laws and statutes of this land, in

violation and in breach of the foresaid leagues,

confederations, and amities, and in grievous

contempt of our said sovereign lord.” (Tudor,

25) Therefore, King Henry issued a proclamation

“Ordering Punishment of Piracy against England’s

Allies” on 17 November 1490.

Our said

sovereign lord the King . . . straightly

chargeth and commandeth that no manner of

person, of what estate, degree, or condition he

be of, from henceforth comfort, take, nor

receive in any of the said ports or other places

of this his realm any of the said misdoers; nor

any merchandises or goods by them spoiled or

taken from any of the said subjects in any

manner of wise, buy or otherwise receive; upon

pain of forfeiture of the same merchandises or

goods, in or to the value thereof, for

restitution thereof to be made to the parties

grieved, and upon pain of imprisonment of their

bodies and otherwise to be punished at the

King’s will. (Tudor, 25-26)

In other words, pirates

who dared to attack friendly ships and dared to sell

their booty would lose their property and be

imprisoned. If further punishment was in order, the

king could inflict whatever he deemed fitting.

His son, Henry VIII, ordered his navy

to pursue pirates and other wayward sea rovers. Four

years after his appointment as Deputy Lord of

Ireland, Sir William Skeffington

encountered a pirate named Broode in 1534. Broode’s

ship wrecked on the shore near Drogheda, and the

mayor and his men rounded up the pirates. In

February 1535, they were hanged, drawn, and quartered

following their trial. But not for piracy. From the

Crown’s perspective, Broode and his men had

committed acts of treason against the king.

Just as Queen Elizabeth excused Lady Killigrew’s egregious

acts, so could juries. This stemmed from the jurors’

perception of who was a pirate and what constituted

piracy, regardless of what the prosecutor and judge

told them. Sometimes, this was because those who

committed such acts did so to survive, especially

during Tudor times. On other occasions, those who

sat in judgement knew the accused; or had dipped

into their purses to acquire pillaged goods for what

they deemed a fairer price than if the items had

first gone through customs; or had provided

necessities that England refused to supply. Every

now and then, jurors didn’t believe defendants were

guilty of piracy if they attacked ships belonging to

non-Christians.

In 1565, Thomas Cobham and Thomas Stukeley were

particularly notorious for their “adventuring.” They

were arrested in May and put on trial, but the jury

acquitted Cobham. Since the High Court of Admiralty

judge suspected this might happen – he thought some

or all of the twelve jurors “were biased or perhaps

bribed” – he took the precaution of only allowing

the Crown to charge the accused with a few crimes.

This allowed him to have Cobham rearrested on new

charges after the jury “had absolved the prisoner.”

(Appleby, 95) Then the Admiralty judge confronted

the jury. Having rendered a false verdict, they had

two options: pay a fine of £20 or serve six months

in gaol. All were also “put in the pillory with

papers stuck on them like a cuirass.” (Appleby, 95)

Cobham was tried again and, this time, he was

to be

taken to the Tower, stripped entirely naked, his

head shaved, and the soles of his feet beaten,

and then, with his arms and legs stretched, his

back resting on a sharp stone, a piece of

artillery is to be placed on his stomach too

heavy for him to bear but not heavy enough to

kill him outright. In this torment he is to be

fed three grains weight of barley and the

filthiest water in the prison until he die.

(Appleby, 95)

His relatives weren’t

keen on this punishment, so they sought a pardon.

Before their request was granted or denied, Cobham

claimed benefit of clergy, which allowed him to show

that he could read Latin just like priests could.

Therefore, being literate, “he could not be done to

death, by the laws of the realm.” (Appleby, 95 &

97) Thomas Stukeley, on the other hand, escaped even

being tried because the evidence against him was too

weak.

World and national events can also impact the

context of what constitutes piracy, which in turn,

affects how laws are interpreted. This

interpretation can then change the laws themselves.

For example, piracy is an act of treason against

whoever rules the country under English law. Then a

period of unrest comes during the late seventeenth

century over who shall rule the country – a Catholic

monarch or a Protestant one. This results in the

Stuart king, James II, fleeing England

after his son-in-law, William of Orange invades. As

far as Parliament sees it, James has abdicated.

James disagrees; he’s merely ruling from afar and

prepares to regain his throne by launching an attack

from Ireland in 1689. One step in accomplishing this

goal is to grant letters of marque to eight

privateers, but when these men are captured and

stand trial five years later, they are charged with

treason. As far as the court sees this, “King James

had lost his sovereignty, in that he has parted with

his crown, and consequently with the power of

granting such commissions.” (Craze, 662) Per this

thinking, James’s letters of marque are invalid and

therefore, the men are committing piracy.

Enter William Oldish (Oldys), an Admiralty lawyer

for the defense who doesn’t rubber stamp this

conclusion. To his way of thinking, everyone and

every institution is equal before the law and the

law must be applied the same without regard to

politics and religion. Since James II is forced to

flee England, his abdication is involuntary and

isn’t recognized by international law. Therefore,

he

still had

a right to wage war and to deploy the tools of

war at his disposal, such as the power to grant

letters of marque, because ‘a king may be

deposed of his crown, but cannot lose his

right.’ (Craze, 663)

Of course, this conflicts

with the government’s perspective, so Oldish is

ousted as the defense advocate. Someone more

compliant is assigned to the case and the trial

proceeds.

While

the combination of Irish identity and probable

Catholicism, plus allegiance to James, weighted

the trial heavily against the men, the Court

convicted only six of the men, with the two

executions being for treason, not piracy. Two

years later, the court pardoned the remaining

four on condition of transportation to America

for seven years. (Craze, 665)

Even though this case

involved privateers, it impacted the question at

hand: What was a pirate? The legal definition

changed, which resulted in a change in the law.

Until this time “piracy” was considered a crime of

treason under the 1536 Offences at Sea Act, and this

law served as the basis for the privateers’ trial in

the first place.3 Based on

Oldish’s thinking, loyalty to sovereign was a matter

of personal choice rather than an obligation. This

contradicted the definition of treason, and

therefore, what the privateers did was actually

steal property rather than defy the king. As a

result, Parliament passed the 1698 Piracy Act. There

was just one caveat: this law had an expiration date

of 1705. Three years later, the Cruizers and Convoy

Act or 1708 Prize Act was enacted, essentially

resurrecting that old favorite, the 1536 Offences at

Sea Act, which defined piracy as an act of treason.

Another nine years passed before Parliament changed

piracy back to a crime of property, rather than

treason, with the 1717 Piracy Act.

What was the 1536

Offences at Sea Act? This piece of legislation came

into being during Henry VIII’s reign. It was

also a time when a primary purpose of the English navy was to ferry

troops from home to wherever they were needed

abroad, usually mainland Europe but sometimes

elsewhere in the British Isles, as opposed to

defending the seas. That task fell to armed merchant ships that

attacked the enemy’s commerce (basically the same

thing that pirates did). Not all of these armed

merchant ships did so legally, and King Henry needed

a way to prosecute those who plundered without the

required legal writ, usually a letter of marque and

reprisal. He also strove to rectify the

fourteenth-century schism between the courts of

assizes and the courts of admiralty. Thus,

Parliament enacted 28 Henry VIII c. 15 (also known

as the 1536 Offences at Sea Act).4 What was the 1536

Offences at Sea Act? This piece of legislation came

into being during Henry VIII’s reign. It was

also a time when a primary purpose of the English navy was to ferry

troops from home to wherever they were needed

abroad, usually mainland Europe but sometimes

elsewhere in the British Isles, as opposed to

defending the seas. That task fell to armed merchant ships that

attacked the enemy’s commerce (basically the same

thing that pirates did). Not all of these armed

merchant ships did so legally, and King Henry needed

a way to prosecute those who plundered without the

required legal writ, usually a letter of marque and

reprisal. He also strove to rectify the

fourteenth-century schism between the courts of

assizes and the courts of admiralty. Thus,

Parliament enacted 28 Henry VIII c. 15 (also known

as the 1536 Offences at Sea Act).4

Where

Traytors, Pirates, Thieves, Robbers, Murtherers

and Confederates upon the Sea, many Times

escaped unpunished, because the Trial of their

Offences hath heretofore been ordered, judged

and determined before the Admiral, or his

Lieutenant or Commissary, after the course of

the Civil Laws,

(2) the Nature whereof is, that before any

Judgment of Death can be given against the

Offenders, either they must plainly confess

their Offences (which they will never do without

Torture or Pains) or else their Offences be so

plainly and directly proved by Witness

indifferent, such as saw their Offences

committed, which cannot be gotten but by Chance

at few Times, because such Offenders commit

their Offences upon the Sea, and at many Times

murther and kill such Persons being in the Ship

or Boat where they commit their Offences, which

should witness against them in that Behalf; and

also such as should bear witness be commonly

Mariners and Shipmen, which, because of their

often Voyages and Passages in the Seas, depart

without long tarrying and Protraction of Time,

to the great Costs and Charges as well of the

King’s Highness, as such as would pursue such

Offenders:

(3) For Reformation whereof, be it enacted by

the Authority of this present Parliament, That

all Treasons, Felonies, Robberies, Murthers and

Confederacies hereafter to be committed in or

upon the Sea, or in any other Haven, River,

Creek or Place where the Admiral or Admirals

have or pretend to have Power, Authority or

Jurisdiction, shall be inquired, tried, heard,

determined and judged . . . as if any such

Offence or Offences had been committed or done

in or upon the Land;

(4) and such Commissions shall be . . . directed

to the Admiral or Admirals . . . to hear and

determine such Offences after the common Course

of the Laws of this Realm, used for Treasons,

Felonies, Murthers, Robberies and Confederacies

of the same, done and committed upon the Land

within this Realm. (Rubin, 397-398)

In essence, whether you

were accused of piracy, theft, robbery, and/or

murder, or participated in one of these acts, you

would be tried under the same rules and regulations

as a traitor. And your trial would be conducted on

land. Before 1536, suspects were tried under civil

law and, if convicted, were sentenced to death. The

problem was in order to receive that judgment, the

accused pirate had to freely confess his crime(s) or

impartial witnesses to the crime must testify to

what they saw. The only way a pirate was likely to

fess up was if the authorities tortured him, which

left eyewitness testimony necessary. Except such

witnesses could only swear to those events that they

actually saw and they could not have been a

participant in the crime, or have an axe to grind,

or have an ulterior motive for bringing down the

pirate. It was also difficult to get such witnesses

to testify because of the transitory nature of being

seamen; most of their time was spent at sea rather

than on land, making it difficult for them to be

available for the trial. This supposed that the

officials could even find such a witness, since many

were killed by the pirates to prevent them from

testifying in the first place.

To alter such an outcome of piracy trials, the

judges were now required to hear these cases under

Admiralty rules, although actual verdicts of guilt

or innocence would be determined by “twelve lawful

Men.” (Rubin, 398) One additional modification was

that the accused could no longer claim “Benefit of

his or their Clergy,” to escape punishment.5

(Rubin, 398)

Notes:

3. At the time, the only other

law that had been passed since that year was the

1670 Piracy Act. It did not serve the Admiralty

court's purposes because it required the master and

seamen of a merchant ship to stop the pirates from

taking their ship. (This placed the onus on the

victims, rather than the government, when it came to

suppressing piracy.)

4. The 1536 Offences at Sea Act

was extended to Ireland in 1613, making Irish law

align with English law.

5. The 1536 Offences at Sea Act

would not be repealed until 2003.

Resources (The list is so

extensive that I have placed it on a separate page.)

Copyright ©2025 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |