Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Suppressing a

Proliferation

Law & Order: Pirate Edition (part 5)

by Cindy Vallar

[I]n the

Afternoon my lieutenant returned aboard and

informed me that he was receiv’d by a great

number of pyrates with much civility to whom he

read the publick the proclamation . . . .

(Hahn, 94)

Captain Vincent Pearse,

commander of HMS Phoenix, recorded this

entry in his log on 24 February 1718. His ship was

anchored in a harbor surrounded by pirate ships.

Ashore, his lieutenant had ventured into the

pirates’ lair to extend a peace offering. Two

hundred nine pirates, including Benjamin Hornigold, would take

advantage of the king’s offer, the first step in

Britain’s attempt to suppress piracy following the War

of the Spanish Succession.

Enlargement of 1715 map of New

Providence.

To the left at Dewitt's Point is the fort. To

the right along the shore of the town harbor

is the redoubt.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Between 1716 and 1726, roughly 4,000 pirates roved

the seas. They posed a significant threat to British

colonists, commerce, and law and order. To bring all

of them to justice would have taken an inordinate

amount of manpower and expense. For this reason,

King George I opted to employ a carrot-and-stick

policy in 1717.

[W]e do

hereby promise and declare, that in case any of

the said Pirates shall, on or before the fifth

Day of September, in the Year of our Lord One

thousand seven hundred and eighteen, surrender

him or themselves to one of our Principal

Secretaries of State in Great Britain or

Ireland, or to any Governour or Deputy Governour

of any of our Plantations or Dominions . . .

every such Pirate and Pirates so surrendering .

. . shall have our gracious Pardon of and for

such his or their Piracy or Piracies, by him or

them committed before the fifth Day of January

next ensuing. (By the King)

If pirates chose not to

take advantage of the amnesty,

[W]e do

hereby strictly Charge and Command all our

Admirals, Captains, and other Officers at Sea,

and all our Governours and Commanders of any

Forts, Castles, or other Places in our

Plantations, and all other our Officers Civil

and Military, to seize and take such of the

Pirates who shall refuse or neglect to surrender

themselves accordingly. (By the King)

In addition, bounties

would be awarded to anyone who brought a pirate to

justice:

for every

Commander of any Pirate Ship or Vessel the Sum

of One hundred Pounds; for every Lieutenant,

Master, Boatswain, Carpenter, and Gunner, the

Sum of Forty Pounds; for every inferior Officer

the Sum of thirty Pounds; and for every Private

Man the sum of twenty Pounds. (By the King)

Should a pirate decide to

turn on his crew mates after 6 September 1718, and

the pirate captain was convicted of his crimes, the

turncoat would earn a reward of £200.

To show that he meant business, the king sent “a

proper Force to be employed for Suppressing the said

Piracies” that consisted of “three fifth-rate

vessels of forty guns each, one sixth rate of twenty

guns and a sloop” to the West Indies; a fifth rate,

a sixth rate, a sloop, and “the forty-gun Pearl”

to Virginia; and “three twenty-gun sixth-rates” to

New England. (Brooks, 374) The primary purpose of

these Royal Navy ships was not to hunt pirates;

rather, they were to protect shipping and intercept

pirates who dared to attack merchant vessels and

inhibit trade.

How effective would these twelve warships be? That

depended on a variety of factors:

a. the

geography and vastness of the region each was to

patrol;

b. their sizes as

compared to those of the pirates;

c. unclean hulls that

slowed down ships and weakened the planks,

allowing for leaks;

d. diseases that

plagued sailors unused to serving in the

Caribbean; and

e. the element of

autonomy that allowed naval captains to refuse

what governors wanted them to do.

Still, King George’s

dispersal was a start, and the Royal Navy would be

more effective in suppressing piracy as the years

passed.

Another decision of the King’s was to put an end to

the private charter given to the proprietors of

Carolina, and to send Woodes Rogers to the Bahamas as its royal governor.

His task was to oust the pirates from New Providence

and restore law and order.

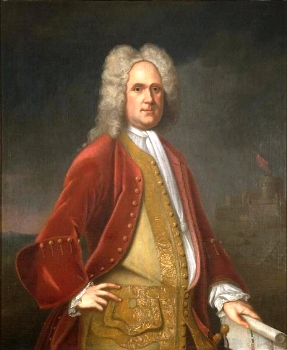

Left: Governor Woodes Rogers

from family portrait by William Hogarth in

1729

Right: Governor Robert Hunter portrait

attributed to Godfrey Kneller in 1720

(Sources: Wikimedia Commons and Wikimedia Commons)

King George’s proclamation wasn’t the first one

issued during this period rife with piracy. Governor

Robert Hunter of New York had issued one in July

1717. It demonstrated that the colony’s interests

were finally on the same page as the Crown’s.

Instead of colluding with pirates, as was common in

earlier years, this proclamation made it clear that

the colonists and sea rovers were now enemies.

Nor was New York the only colony that began cracking

down on pirates. In October 1717, Massachusetts

brought charges against eight pirates for the first

time since John Quelch’s trial. This time

around, the defendants were members of Sam Bellamy’s crew: Simon Van

Vorst, John Brown, Thomas Baker, Hendrick Quintor,

Peter Cornelius Hoof, John Shuan, Thomas South, and

Thomas Davis. The charges against them involved

“piracy, robbery & felony committed on the high

sea.” (Trials, unnumbered) Prior to pleading,

they requested assistance from an attorney, and

Robert Auchmuty was chosen. One of his objections

involved the laws under which they were being tried:

That the

Commission of the late Queen Anne was of no

force after Her Majesty’s Demise: And so the

Court had no Power to act by vertue of the said

Commission, It having dyed with the Queen: And

several Authorities in the Law were Cited and

Insisted upon . . . . (Trials, 4)

The court said the

opposite was true.

[T]he

Proclamation of His present Majesty King GEORGE,

for Continuing Officers, and the subsequent

Commission, and the Instructions from the Crown

lately Transmitted to the Governour, referring

to the Pirates was a sufficient justification of

the above-mentioned Act, which was still in full

force; and that the cases which had been Cited,

were not to the purpose. (Trials, 4)

The defendants pleaded

not guilty. The trial began the next day with the

Advocate General orating on the egregiousness of

piracy.

Now as

Piracy is in its self a complication of Treason,

Oppression, Murder, Assassination, Robbery and

Theft, so it denotes the Crime to be perpetrated

on the High Sea . . . whereby it becomes more

Atrocious.

First, Because it is done in

remote and Solitary Places, where the weak and

Defenceless can expect no Assistance nor Relief;

and where these ravenous Beasts of Prey may

ravage undisturb’d, hardned in their Wickedness

with hopes of Impunity, and of being Concealed

for ever from the Eyes and Hands of avenging

Justice. One of the most aggravating

Circumstances, that attend a Crime, is the

facility of it’s being committed, that is, where

the Malefactor cannot easily be prevented nor

discovered. Thus by the Law of GOD Theft in the

Field was more grievously Punished, than Theft

in a House. . . .

Another Aggravation of this Crime

is, That the unhappy Persons on whom it is

acted, are the most innocent in themselves, and

the most Useful and Beneficial to the Publick; .

. . Ships are under the Publick Care . . .

Masters of Ships are Publick Officers, and

therefore every Act of Violence and Spoliation

committed on them or their Ships, may justly be

accounted Treason, and so it was before the

Statute of the 25th of Edward III.

The Third Circumstance,

which blackens exceedingly and augments a

Pirates Guilt, is the Danger, wherewith every

State or Government is threatned from the

Combinations, Conspiracies and Confederacies of

Profligate and Desperate Wretches, united by no

other tie . . . than a mutual Consent to

extinguish first Humanity in themselves, and to

Prey promiscuously on all others. (Trials,

6-7)

After this explanation

regarding “the Nature and Effects of Piracy in

General,” he then addressed “Principles of the Civil

Law” that the court was obligated to follow and

which dictated appropriate punishments for the crime

if the defendants were convicted. Only after this

were witnesses called. The defendants also offered

their testimonies. Van Vorst, Brown, Baker, Quintor,

Hoof, and Shuan were found guilty, but South was

acquitted. As per the law, the six felons

shall go hence to the Place from

whence you came, and from thence you shall be

carryed to the Place of Execution, and there you

and each of you, shall be hanged up by the Neck

until you & each of you are Dead; And the

Lord have Mercy on your Souls. shall go hence to the Place from

whence you came, and from thence you shall be

carryed to the Place of Execution, and there you

and each of you, shall be hanged up by the Neck

until you & each of you are Dead; And the

Lord have Mercy on your Souls.

And the

Court do also ordain, That all your Lands,

Tenements, Goods and Chattles be forfeited to

the King, and brought into His Majesty’s use.

(Trials, 14)

The convicted pirates

were hanged on 15 November “at Charlestown Ferry

within flux and reflux of the Sea.” (Trials, 14)

As for Thomas Davis, the vice-admiralty court heard

his case on 28 October. Since Thomas South had been

acquitted, he could now appear as a witness. He

explained that Davis had been forced to join the

pirates, who refused to allow him his freedom

because of his carpentry skills. “[T]hey would shoot

him before they would let him go from them.” (Trials,

19) Several others testified on his behalf as well.

When it was Davis’s turn to speak, he explained how

he came to be aboard the pirate ship and how he

survived her sinking.

John Valentine, an attorney whom the court had

chosen to speak for Davis, then said,

if he

believed the Prisoner to be guilty of the

crimes, for which he was Indicted, he should not

appear on his behalf: That he hoped this

Honourable Court upon consideration that there

was little or nothing said, much less proved

against the Prisoner, they would acquit him as

being Innocent, for that in all Capital crimes

there must be down-right Proofs and plentiful

Evidence to take away a Mans Life . . . . (Trials,

20)

Although the prosecutor

did not concur and had quite a lot to say on Davis’s

guilt, the Court “were of Opinion that there was

good proof of the Prisoners being forced on board

the Pirate Ship . . . which excused his being with

the Pirates; and that there was no Evidence to prove

that he was Accessory with them, but on the contrary

that he was forced to stay with them against his

Will.” (Trials, 22) The verdict? Not Guilty.

Notwithstanding the warships sent to suppress

piracy, or the fact that King George extended his

Act of Grace to incorporate piracies committed

through 5 January 1719, and that pirates then had

until 1 July 1719, to turn themselves in, piracy

remained a problem. Governors repeatedly sought

additional help from London. Such requests either

fell on deaf ears or weren’t reacted to in a timely

manner.

In

July 1718, Lieutenant-Governor Alexander Spotswood,

never a friend of pirates, grew concerned at the

presence of such scoundrels in his colony. He shared

with Virginia’s Council that In

July 1718, Lieutenant-Governor Alexander Spotswood,

never a friend of pirates, grew concerned at the

presence of such scoundrels in his colony. He shared

with Virginia’s Council that

Severall .

. . Pirates have Since come into this Colony

with Certificates from the Governor of No

Carolina of their Surrendering to him, but in

regard their Travelling about the Country with

their Arms and keeping together in Considerable

Numbrs give Great Suspicion, that they design to

betake themselves again to Piracy. (Executive,

481)

As a result, Spotswood

issued a proclamation that insisted that

all Persons who have been concerned in any

Piracys, and who shall come into this Colony

immediately upon their Arrival, to deliver up

their Arms to the first Justice of the Peace or

Milletary Officer, and prohibiting them to

Associate in any Greater Numbers than three in one

Company And that in Case any be found going armed,

or in Greater Numbers than is above Expressed,

That the Justices of the Peace Cause them to be

taken up and put in Prison till they give Security

for their good behavior. (Executive,

481-482)

To his way of thinking, this proclamation was not

enough. Fed up with North Carolina’s failings when

it came to dealing with pirates, and desiring to

prevent the pirates from adversely affecting

Virginia’s trade, Spotswood took matters into his

own hands.

[H]aving

at the same time received complaints from . . .

the trading people [of North Carolina] of the

insolence of [Thache and] that gang of pyrates,

and the weakness of that Governmt. to restrain

them, I judged it high time to destroy that crew

of villains, and not to suffer them to gather

strength[.] (America, 800)

He gathered the necessary

intelligence about Blackbeard and his men, and

solicited help from pilots familiar with North

Carolina waters. He met with the warship captains

stationed at Virginia and they formulated a plan. At

his expense,

I hyred

two sloops and put pilotes on board, and the

Captains of H.M. ships having put 55 men on

board under the command of the first Lieutenant

of the Pearle and an officer from the Lyme,

they came up with Tach at Ouacock Inlett on the

22nd of last month. (America, 800)

In the ensuing fight against Robert Maynard and his

men, “Tach with nine of his crew were killed, and

three white men and six negros were taken alive but

all much wounded.” (America, 800) The Royal Navy

lost eleven men and another twenty-three sustained

wounds. As to why Spotswood chose not to get prior

approval, he explained, “I did not communicate to

the Assembly nor Council, the project then forming

agt. Tach’s crew for fear of his having

intelligence, there being in this country and more

especially among the present faction, an

unaccountable inclination to favour pyrates . . . .”

(America, 800)

Governing a colony far from home often meant the

governors, like Spotswood, were left to their own

devices when it came to dealing with pirates.

Guidance in the specifics of what to do was either

sparse or not forthcoming. In 1661, during his

tenure as governor of Jamaica, Colonel Edward

D’Oyley (or Doyley) arrested the men who sailed

aboard Betty and Pearl because

they had attacked a Dutch vessel. Since these were

the early days of the English colony, there was no

gaol in which to imprison them. Instead, their

sentences involved manual labor on the plantations

of the island’s various officers. If anyone thought

to succor these men, the colonel proclaimed not to

comfort or

abet the said Theeves and piratts nor any waies

promote advise or consort upon pain of being

prosecuted as accessories to the said Robbery

and piracy in according to the law. (Hanna,

103)

To make certain the

residents specifically knew who these men were, he

had them wear arrows on their necks. This punishment

lasted for as long as he thought them unrepentant.

One was a young man named “henry Morgan, souldier.”

(Hanna, 103)

With navies stretched thin and governments focused

more on European events than West Indian ones,

colonial governors sometimes improvised to protect

their domains. In 1665, manipulation of the law was

the sleight of hand that Jamaican governor Sir

Thomas Modyford employed. Authorities in London

expected him to implement the law and heed their

instructions, but they weren’t on the scene and

didn’t necessarily understand the full picture. He

randomly selected fourteen pirates and put them on

trial. Since they were found guilty, according to

the 1536 Offences at Sea Act, they were to be

hanged. Except, the whole trial had been rigged to

show England that he was maintaining law and order

on the island. Now that he had achieved that aim, he

pardoned the condemned and commissioned them to go

privateering against the Dutch since England was at

war with them.

Even pirates tried to manipulate the law to their

advantage. George Cusack was caught in a

compromising position and arrested in England in

1674. After the indictment was read against him and

five others, he was asked to plead, but

first took

some exceptions to the Jury; not for any

prejudice against any particular men of them;

but because they were Citizens; who did not (he

said) understand Maritime-Affairs. . . .

Sea-Captains, and Masters of Ships should have

been Impannell'd. . . . [H]e cryed out, We will

be Tryed (my Lord) by men of our own Trade!

Which being understood in another sence, made

not only the Audience, but his fellow Prisoners

to laugh heartily. (Grand, 30)

The Court overruled his

objection, perhaps because the current jury was more

likely to find him guilty, whereas if men of the sea

sat in judgment, they were more likely to acquit him

since they tended to protect their own.

This Mr.

Cusack appeared to be a Person of a Clear

Courage, and good understanding: he pleaded very

well for his life; but the matter was too foul

to be washt off with good words. (Grand,

31)

He and the other

defendants were found guilty and hanged in 1675.

To be continued . . .

Resources (The list is so

extensive that I have placed it on a separate page.)

Copyright ©2025 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |