Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

The Evolution &

Suppression Continue

Law & Order: Pirate Edition (part 3)

by Cindy Vallar

When Elizabeth I came to power in

1558, she began instituting changes that subtly

altered how England defined piracy. Her policies saw

pirates as “unlicensed sea-raiders” rather than

traitors. (Craze, 659) In March of 1751, she issued

five directives regarding English coasts. When Elizabeth I came to power in

1558, she began instituting changes that subtly

altered how England defined piracy. Her policies saw

pirates as “unlicensed sea-raiders” rather than

traitors. (Craze, 659) In March of 1751, she issued

five directives regarding English coasts.

1st. That

no pirate of whatever nation shall enter any of

her ports or the Downs, under penalty of losing

the ship which he brings, and imprisonment for

himself.

2nd. That no

subject of the Queen, or other inhabitant of her

realm, shall send or supply any victuals or

stores of any sort to the said pirates, and

shall not receive goods from them, or deal with

them directly or indirectly.

3rd. That it is

the Queen’s will that these clauses shall be

obeyed, and that any infraction of them shall be

punished by the arrest of the offenders by the

Governors of the ports, to be held until further

orders from the Queen and Council.

4th. That any

person found culpable, after the publication of

this, shall be punished as a disturber of the

Queen’s peace.

5th. That any

subject of the Queen who may have offended in

this way, and will make confession of the same,

and declare those whom he knows to be guilty,

shall be himself pardoned. (Simancas, 4

March. 239)

These declarations proved

ineffectual, possibly because no one paid attention

to them. On 23 August, the Spanish ambassador to

England wrote to King Felipe II that

the guns

from the castle and ramparts of Dover had

prevented Flemish ships from taking the

twenty-four pirate vessels which were there.

Twentytwo of them are now on the beach, our

ships having captured the other two. The pirates

have left a few of their sailors in charge of

them and the captains and rest of their people

have come to London. The assertions made at

Court that the pirates would be arrested is not

true . . . . (Simancas, 23 Aug., 273)

Rather than condone

piracy, which was what Elizabeth seemed to be doing,

Felipe II of Spain had a different way of halting

piracy. Sir Richard Hawkins, one of

Elizabeth’s Sea Dogs, wrote,

[I]f this

Spanish shippe should fall athwart his King’s

armado or gallies, I make no doubt but they

would hang the captaine and his companie for

pirates . . . by a speciall law, it is enacted,

that no man in the kingdomes of Spaine, may arme

any shippe, and goe in warre-fare, without the

King’s speciall licence and commission, upon

paine to be reputed a pirate, and to be

chastised with the punishment due to corsarios.

(Hawkins, 232)

When James I ascended the English

throne in March 1603, he wanted peace, and to

achieve that he was determined to bring about an end

to piracy no matter what. He issued numerous

proclamations to ensure this happened. In October,

Secretary Giovanni Carlo Scaramelli sent a missive

to his superior, the Venetian Doge, and the Senate.

English pirates had attacked the Venetian

ambassador’s ship and stolen from him.

The Judge

of the Admiralty (Aldemari) has been for two

days in Southampton, drawing up the indictment

against the pirates . . . Five . . . have been

arrested, and on their information more stolen

goods are being discovered. The prisoners insist

that the ship they sacked was not Venetian,

though the money and the nature of the goods

prove it to have been so; but the judge says . .

. that without a confession from one of them, or

further proof, would it be possible to condemn

them to death. (Venice, Oct. 22., 145.)

Scaramelli’s words

emphasized the fact that without the pirates fessing

up or witnesses testifying to the defendants’

criminal acts, English law basically assured that

they would get away with their crimes. James was fed

up with such marauding, each act like a slap to the

face, so he issued a proclamation, which Scaramelli

included with his report. This time, James also went

after those who abetted the pirates.

A

Proclamation to repress all Piracies and

Depredation upon the Sea.

The King is

informed, through the manifold and daily

complaints made by his own subjects and by

others, of continual piracies and depredations,

“committed on the seas by certaine lewd and

ill-disposed persons.” The ordinary proceedings

have proved ineffectual to stop the mischief.

He now makes the

following order: –

Pain of death,

not only for Captain and mariners, but for

owners and victuallers of any “man-of-warre,”

which shall commit piracy, depredation, or

“murther at the sea upon any of his Majesties

friends.”

Pain of death

for anyone who seizes any goods belonging to

subjects of allies.

All fresh

“Admirall causes” to be summarily tried by

Admiralty Judge.

No appeal from

his sentence.

“No prohibition

in such cases of spoile and their accessories or

dependances be granted hereafter.”

A record of the

restitutions to strangers to be kept.

All

Vice-Admirals to certify the Court of Admiralty

every quarter of all “men-of-warre” put to sea,

or returned home with goods taken at sea, or the

produce thereof, the fine of forty pounds for

each breach of this order.

The King’s

subjects shall forbear from aiding or receiving

any “Pirat or sea rover,” and likewise from all

traffic with them.

The

Vice-Admirals, “Customers,” and other officers

shall not allow any ship to go to sea without

first searching her, to see whether she is

furnished for the wars and not for fishing or

trade. In any case of suspicion, good surety

shall be exacted before they let the ship sail.

The officers shall answer for such piracies as

may be committed by those who have sailed with

their licence.

“Divers great

and enormous spoyles and piracies have been of

late tyme committed within the Straits of

Gyblaltar by Captain Thomas Tomkins, gentleman,

Edmond Bonham, Walter Janverin, mariners, and

goods and moneys brought by them to England have

been scattered, sold, and disposed of “most

lewdly and prodigally, to the exceeding

prejudice of his Majesties good friends, the

Venetians.” All officers are to arrest these

malefactors.

“Given at his

Majesties City of Winchester.” 30th September,

1603. (Venice, Oct. 22., 146.)

This and seven subsequent

proclamations attempted “to turn back the clock,

past the privateering commissions of Elizabeth and

even the laissez-faire policies of Henry VIII and

his predecessors, all the way to Edward III.”

(Burgess, Pirates, 30) To make certain that

juries did not sympathize with accused pirates and

acquit them, they would be tried “by the Judge of

the High Court of the Admiralty without admitting

unnecessary delay, and no appeal from him shall be

allowed to the defendant.” (Burgess, Pirates,

30)

These measures looked good on paper, but laws were

only part of the battle. Order, or follow-through,

in obtaining convictions and carrying out

punishments, was also important to the effectiveness

of these laws. In actuality, few pirates were

brought to justice. Eventually, James tried offering

pardons; pirates took advantage of these but often

returned to new plunderings.

Charles II (1660-1685) tried a

different tack to curb piracy when Parliament passed

the 1670 Piracy Act (Chapter 11 22 and 23 Car Cha

2).6

This put the onus on the captains and their crews to

stop piracy. Rather than just give up without a

fight, which authorities saw as detrimental to

English trade and the nation’s reputation, merchant

ships were expected to be armed and to engage any

would-be sea rovers. If the master of any Charles II (1660-1685) tried a

different tack to curb piracy when Parliament passed

the 1670 Piracy Act (Chapter 11 22 and 23 Car Cha

2).6

This put the onus on the captains and their crews to

stop piracy. Rather than just give up without a

fight, which authorities saw as detrimental to

English trade and the nation’s reputation, merchant

ships were expected to be armed and to engage any

would-be sea rovers. If the master of any

English

Shipp . . . of the Burthen of two hundred Tunns

or upwards and mounted with sixteene Gunns or

more . . . shall yeild up the said Goods to any

Turkish Shipps or Vessells, or to any Pirates or

Sea rovers whatsoever without fighting . . . the

Master shall upon proofe thereof made in the

High Court of Admiraltie be from thenceforth

incapeable of takeing charge of any English

Shipp or Vessell as Master or Commander thereof

. . . .

If the master ignored

this ruling and was discovered, six months

imprisonment for each offense was warranted. For

those who commanded vessels of lesser tonnage and

armament who failed to defend themselves, they were

liable to suffer each and every “Penaltyes”

mentioned in the piracy act. One of these included

the seizure, by the Admiralty, of the ship in

question.

The authorities also had the right to go after any

members of the crew who failed to do what was

expected of them in defense of the ship, cargo, and

themselves.

. . . if

the Marriners or inferiour Officers of any

English Shipp laden with goods and merchandices

as aforesaid shall decline or refuse to fight

and defend the Shipp when they shall be

thereunto commanded by the Master or Commander

thereof, or shall utter any words to discourage

the other Marriners from defending the Shipp,

That every Marriner who shall be found guilty of

declineing or refuseing . . . shall loose all

his Wages due to him together with such goods as

he hath in his Shipp, and suffer Imprisonment

not exceeding . . . six monthes and shall

dureing such time be kepte to hard labour . . .

.

If the captain wished to

fight against the pirates, but the men used force to

prevent him from doing so, the guilty seamen “shall

suffer death as a Felon.”

To provide the master and crew with an incentive to

fight against their attackers, the ship’s owners

were expected to pay each of them up to three pence

per each pound of the cargo’s value. If any seaman

was killed or sustained incapacitating wounds, this

money was expected to go to his widow and/or

children.

As the legalities of privateering and the

obligations required of merchant ships changed,

another shift began albeit at a slower pace. This

stemmed from the fact that merchants and plantation

owners became more important to the economy of

England and her colonies. The growth of that

importance manifested itself in their increasing

power to influence Parliament and legislatures.

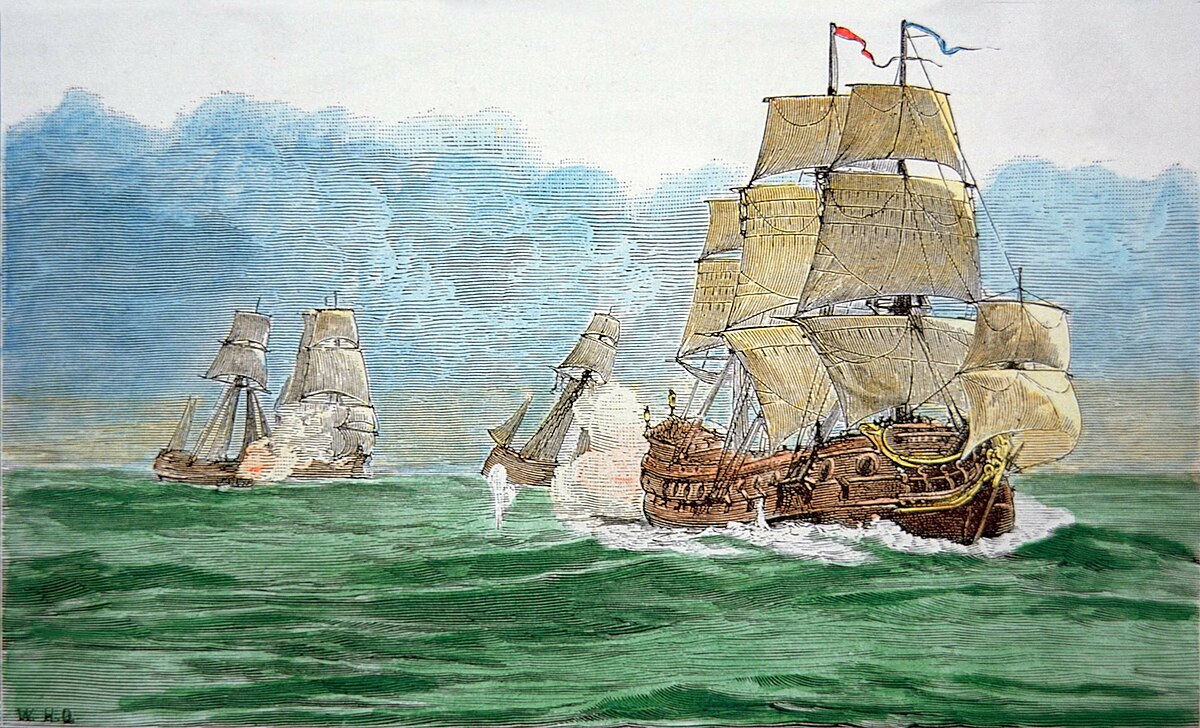

Another incident that influenced how piracy was

perceived and, in time, resulted in new laws being

passed involved a pirate attack in the Indian

Ocean. In 1695, Muslim pilgrims were returning from

Mecca when Henry Every, Thomas Tew, and other pirates

attacked Fateh Muhammed and Ganj-i-Sawai,

Emperor Aurangzeb’s flagship. Enraged, the emperor

and his people lashed out at the English closest to

hand, those associated with the East India Company (EIC). At

the factory in Surat, sixty-three Englishmen were

shackled and imprisoned three to a cell. Contact

with anyone outside the factory walls was strictly

forbidden. Some were badly beaten; one was stoned

and died. They remained prisoners until almost the

end of June 1696.

In response to Emperor Aurangzeb’s outrage

and demand for justice, England’s Privy Council

issued the following proclamation in William III’s name.

William By

the Grace of GOD, King of Great-Britain, France

and Ireland . . . are Informed that Henry Every,

alias Bridgeman, together with several other

Persons . . . to the Number of about One Hundred

and Thirty, did . . . Commit several Acts of

Pyrracy . . . And that the said Henry Every, and

severals of his Accomplices, since . . . are

Returned to, and have Dispersed themselves

within this Our antient Kingdom, thinking, and

intending thereby to Save & Shelter

themselves from the Punishment & Execution

of Law . . . We being Resolved, that outmost

Diligence shall be Used for Seizing, and

Apprehending the Persons of such Open and

Villanous Transgressors; Do therefore . . .

Command, the Sheriffs . . . and Our Good

Subjects . . . to do their outmost Indeavour and

Diligence to . . . Apprehend the Persons of the

said Henry Every . . . together with . . . his

Accomplices, . . . and . . . Deliver him

or them Prisoners to the next Magistrat of any

of Our Burghs, to be by them keeped in safe

Custody until farther Order be taken for

bringing him or them to such . . . Punishment as

their Crime does Deserve, . . . and for

Incouraging the Magistrats . . . and any other

of Our Good Subjects to Search for, and

Apprehend such Nottrorious Rogues: We . . . do

make Offer, and Assure the Payment of the Sum of

Five Hundred Pounds Sterling for the said Henry

Every . . . and Fiftieth Pounds Sterling . . .

for every one of the other Persons . . . to any

Person or Persons who shail Seize and Apprehend

them or any of them, and Deliver him or them

Prisoners to any of the Magistrats of Our Burghs

. . . . (Proclamation)

Every eluded the

authorities, but six of his men were apprehended and

tried. When the jury returned its verdict, they

acquitted the men. One EIC official opined, “Some of

the old hardened Pirats said, they lookt on it as

little or no sin to take what they could from

Heathens as the Moors and other Indians were.”

(Hanna, 203) Perhaps the jury shared that sentiment.

Of course, not everyone thought well of the EIC, and

a verdict of innocence allowed the jury to give the

Company a bit of comeuppance.

The acquittal was a slap in the face to the Crown

which wanted to show how tough England could be on

pirates. Determined to see the pirates brought to

justice, the Crown tried a different tact. It tried

the six men a second time – just not for their

offenses against India. The new charges stemmed from

crimes (mutiny being one) committed against England,

and this jury declared the pirates guilty and the

six were executed. In all, only twenty-four members

of Every’s crew were ever brought to justice.

One result of Every’s attack and the subsequent

debacle in court was that the Board of Trade and

Plantation became an independent body, instead of

being answerable to the Privy Council. It was now

the board’s responsibility to examine all laws and

regulations passed in the colonies. These would no

longer be permitted to clash with England’s trade

policies.

Another

outcome concerned the law against piracy. In 1696,

pirates had to be tried in England, even if they

committed their crimes anywhere else in the world.

This was part of Henry VIII’s 1536 Offences at Sea

Act. Many felt this requirement was archaic, in

addition to being expensive for individual colonies

to afford. If an arrested pirate was to be

transported to England, was he notorious enough or

was his case of political worth to warrant the

expense of sending him to England? One of the few

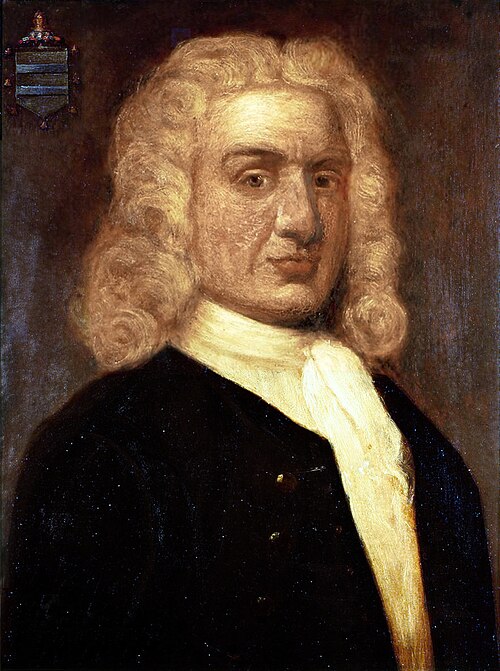

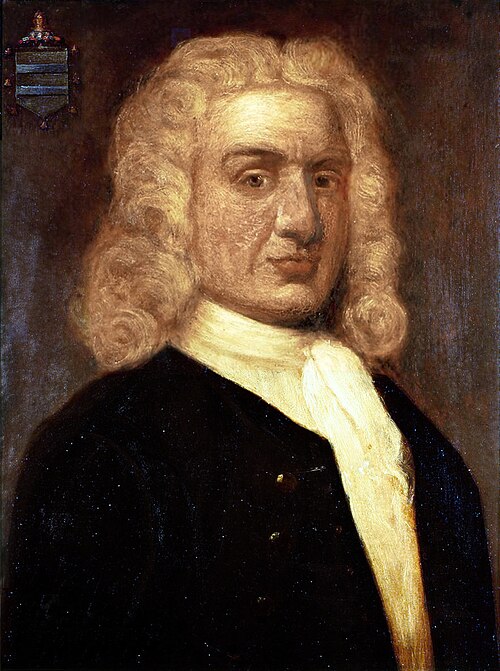

who were deemed to fall into either category was William Kidd, but what about

every other pirate who was arrested? A new law was

needed to remedy this, but since pirates were akin

to being traitors under Henry’s law, it was

necessary to revisit the definition of piracy. To

that end, Sir Charles Hedges, an Admiralty Court

judge, was approached. His legal perspective was

that Another

outcome concerned the law against piracy. In 1696,

pirates had to be tried in England, even if they

committed their crimes anywhere else in the world.

This was part of Henry VIII’s 1536 Offences at Sea

Act. Many felt this requirement was archaic, in

addition to being expensive for individual colonies

to afford. If an arrested pirate was to be

transported to England, was he notorious enough or

was his case of political worth to warrant the

expense of sending him to England? One of the few

who were deemed to fall into either category was William Kidd, but what about

every other pirate who was arrested? A new law was

needed to remedy this, but since pirates were akin

to being traitors under Henry’s law, it was

necessary to revisit the definition of piracy. To

that end, Sir Charles Hedges, an Admiralty Court

judge, was approached. His legal perspective was

that

piracy is

only a sea term for robbery, piracy being a

robbery committed within the jurisdiction of the

Admiralty.

If any man be assaulted within that

jurisdiction and his ship or goods violently

taken away without legal authority, this is

robbery and piracy. (Brooks, 61)

Two years later, William

III’s An Act for the more effectuall

Suppressions of Piracy reinforced this

definition of piracy.7 It also

explained why there was a need for altering where

trials would be held.

Persons

committing Piracies Robberies and Felonies on

the Seas in or neare the East and West Indies

and in Places very remote cannot be brought to

condign Punishment without great Trouble and

Charges in sending them into England to be tryed

within the Realme

and this reticence to

bring justice to the pirates persuaded honest seamen

that they had little to fear from turning pirate and

“that sort of wicked Life.” (William III) As a

result of the lack of prosecutions,

the

Numbers of them are of late very much increased

and their Insolencies soe great that unlesse

some speedy Remedy be provided to suppresse them

by a strict and more easie way for putting the

ancient Laws[,]

the situation would just

get worse. Consequently, captured pirates could now

be tried in vice-admiralty courts in any dominion

over which the English monarch ruled, instead of

returning the accused to England to stand trial.

Seven men were to sit in judgment, one of whom must

be “President or Chiefe of some English Factory or

the Governour Lieutenant Governour or Member of His

Majesties Councills in any of the Plantations or

Colonies aforesaid or Commander of one of His

Majesties Shipps.” (William III) The remainder could

consist of merchants, factors, planters, naval

officers, and masters of English merchant ships.

The oaths and procedures for a vice-admiralty court

trial were spelled out and those who sat in judgment

were to be impartial. Each accused must state

whether he was guilty or not guilty; if he refused

to plead, “he shall suffer such Pains of Death Losse

of Lands Goods and Chattells and in like manner as

if he or they had beene attainted or convicted upon

the Oath of Witnesses or his owne Confession.”

(William III) In other words, no plea was equivalent

to a guilty plea. If a pirate declared that he was

not guilty,

Witnesses

shall be produced . . . and duely sworne and

examined . . . in the Prisoners presence And

after a Witnesse hath answered all the Questions

proposed by the President of the Court and given

his Evidence it shall and may be lawfull for the

Prisoner to have the Witnesse crosse-examined by

first declaring to the Court what Questions he

would have asked and thereupon the President of

the Court shall interrogate the Witnesse

accordingly and every Prisoner shall have

liberty to bring Witnesses for his Defence . . .

and afterwards the Prisoner shall be fairly

heard what he can say for himselfe[.] (William

III)

When all was said and

done, the prisoners were taken away to allow the

judges to debate and vote on the guilt or innocence

of the accused. Once that was decided, the prisoners

returned to court to hear their fates. If “attainted

[they] shall be executed and put to Death at such

time in such manner and in such place upon the Sea

or within the ebbing or Flowing thereof as the

President or the major part of the Court . . .

directed”. (William III)

This act also conferred the status of pirate upon

any master or seaman who went on the account. This

included anyone who acted as a go-between or tried

to corrupt crews. Those who mutinied were also

deemed pirates. Chapter nine of the statute

concerned those who aided and abetted pirates.

And

whereas severall evill disposed Persons in the

Plantations and elsewhere have contributed very

much towards the Encrease and Encouragement of

Pirates by setting them forth and by aiding

abetting receiving and concealeing them and

their Goods and there being some Defects in the

Laws for bringing such evill disposed Persons to

condigne Punishment Be it enacted by the

Authority aforesaid That all and every Person

and Persons whatsoever who after the Twenty

ninth Day of September in the Yeare of our Lord

One thousand seaven hundred shall either on the

Land or upon the Seas wittingly or knowingly

sett forth . . . are hereby declared and shall

be deemed and adjudged to be accessary to such

Piracy and Robbery done and committed[.] (William

III)

This included anyone who

helped the pirates after the fact, as well as

before, and if found guilty, each suffered the same

punishment as if he or she had been a pirate.

This law also addressed compensation for killed or

wounded seamen and rewards for informers. Any

governor who refused to adhere to this act forfeited

“all and every Charters granted for the Government

or Propriety of such Plantation.” (William III)

To be continued . . .

Notes:

6. Although enacted, there are no

extant documents to show whether anyone was ever

prosecuted under this act, according to Sarah Craze.

7. An interesting side note to

William’s anti-piracy legislation is that in 1700,

the Board of Trade issued “An act to punish

governors of plantations in this kingdom for crimes

committed in the plantations.” (Burgess, Politics,

193) The reasoning behind this was that colonial

governors who were chummy with pirates were

violating their charters, and therefore, the Board

decided to criminally prosecute such governors.

Resources (The list is so

extensive that I have placed it on a separate page.)

Copyright ©2025 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |

When

When

Another

outcome concerned the law against piracy. In 1696,

pirates had to be tried in England, even if they

committed their crimes anywhere else in the world.

This was part of Henry VIII’s 1536 Offences at Sea

Act. Many felt this requirement was archaic, in

addition to being expensive for individual colonies

to afford. If an arrested pirate was to be

transported to England, was he notorious enough or

was his case of political worth to warrant the

expense of sending him to England? One of the few

who were deemed to fall into either category was

Another

outcome concerned the law against piracy. In 1696,

pirates had to be tried in England, even if they

committed their crimes anywhere else in the world.

This was part of Henry VIII’s 1536 Offences at Sea

Act. Many felt this requirement was archaic, in

addition to being expensive for individual colonies

to afford. If an arrested pirate was to be

transported to England, was he notorious enough or

was his case of political worth to warrant the

expense of sending him to England? One of the few

who were deemed to fall into either category was