Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

A Test Case

Law & Order: Pirate Edition (part 4)

by Cindy Vallar

The first

trial held under William III’s An Act for the

more effectuall Suppressions of Piracy in

Colonial America concerned John Quelch.8

He had been hired as first mate aboard the privateer

Charles. The captain fell ill, and Quelch

assumed command. Instead of going after enemy ships,

Quelch and his men attacked Portuguese vessels off

the coast of Brazil in November 1703. At the time,

England and Portugal were allies, which made their

attacks acts of piracy. In May 1704, Quelch and his

men put into port at Marblehead, Massachusetts, and

it wasn’t long before their purchases raised the

residents’ suspicions. More than just Charles’s

owners believed that Quelch and his men were

actually pirates. The influx of gold and silver also

concerned Governor Joseph Dudley,

because actual currency could devalue the colony’s

bills of credit. (At the time its commerce was based

primarily on bartering.) The authorities issued

orders for their arrest and the confiscation of the

ill-gotten currency. Dudley took care of helpers and

hinderers of these orders as well.

Whosoever shall discover &

Seize any of the Pirates or Treasure concealed,

and deliver them to Justice, shall be Rewarded

for their Pains. Whosoever shall discover &

Seize any of the Pirates or Treasure concealed,

and deliver them to Justice, shall be Rewarded

for their Pains.

And any who

conceal or have in their custody any of the said

Treasure, & shall not disclose and make

known the Quantity & Species, & render

the same unto the Commissioners appointed for

that purpose, within the space of Twenty Days

next after the Publication hereof at Boston,

shall be alike proceeded against. (Beal,

139)

Before long, twenty-five

out of forty-three pirates were captured and seventy

ounces of gold and seventy of silver were turned in.

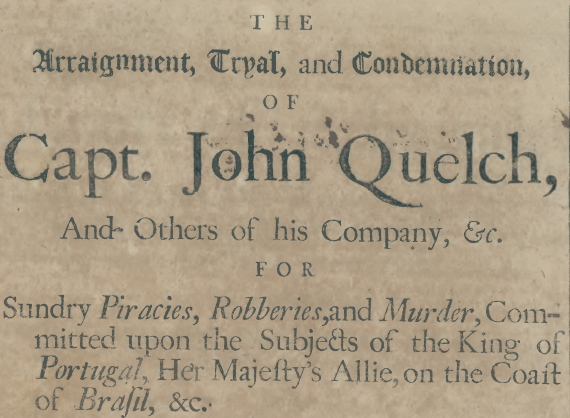

Quelch and others were arraigned and tried on

charges of “Piracies, Robberies, and Murder” in June

according to “the Statute made in the Eleventh and

Twelfth Year of the late King WILLIAM . . . An

Act for the more effectual Suppression of Piracy.”

(Arraignment, 1)

The record of the proceedings included specific

dates and places of their attacks, as well as what

plunder they took and its value. John Clifford,

Mutatis Mutandis, Matthew Pimer, and James Parrot

pled guilty, before Clifford, Pimer, and Parrot were

“received into the Queen’s Mercy, and . . . declared

Witnesses in behalf of the Queen, against John

Quelch and Company . . . .” (Arraignment,

4)

Quelch pled not guilty and asked for time to prepare

for the trial with the assistance of an attorney.

The court granted this request, assigning James

Meinzies to “assist you, and offer any Matter of Law

in your behalf upon your Tryal”, and gave them until

“Friday Morning next, at Nine of the Clock” (16

June) to do so. (Arraignment, 4) Meinzies

would also aid twenty other accused pirates: James

Austin, Dennis Carter, John Carter, John Dorothy,

Charles James, William Jones, Charles King, Francis

King, John King, John Lambert, Richard Lawrence,

John Miller, Benjamin Perkins, Erasmus Peterson,

John Pitman, Nicholas Richardson, Peter Roach,

Christopher Scudamore, John Templeton, and William

Wilde.

One the sixteenth, Queen’s Advocate Paul Dudley

outlined why the court was assembled.

A

Pyrate was . . . justly called by the Romans, Hostis

Humani Generis: And the Civil Law saith of

them, that neither Faith nor Oath is to be kept

with them; and therefore if a Man that is a

Prisoner to Pirates, for the sake of his

Liberty, promise a Ransom, he is under no

Obligation to make good his Promise; for Pirates

are not Entituled to Law, not so much as the Law

of Arms; for which Reason ’tis said, if Piracy

be commited upon the Ocean, and the Pirates in

the Attempt happen to be overcome, the Captors

are not obliged to bring them to any Port, but

may exposs them immediately to Punishment, by

Hanging them at the Main-Yard: A sign of its

being of a very different and worse Nature than

any Crime committed upon the Land; for Robbers

and Murderers, and even Traytors themselves,

mayn’t be put to Death without passing a formal

Tryal: And if the fate of the Prisoner at the

Bar, with his Company, had allowed them to have

been overcome in their Piracies, &c. and

immediately hung up before the Sun, it had been

very just upon them. But being then suffered to

live, and now brought unto a Court of Justice,

they are to be used, treated, and tryed as the

Laws of England, and our own Country do

direct. (Arraignment, 5) A

Pyrate was . . . justly called by the Romans, Hostis

Humani Generis: And the Civil Law saith of

them, that neither Faith nor Oath is to be kept

with them; and therefore if a Man that is a

Prisoner to Pirates, for the sake of his

Liberty, promise a Ransom, he is under no

Obligation to make good his Promise; for Pirates

are not Entituled to Law, not so much as the Law

of Arms; for which Reason ’tis said, if Piracy

be commited upon the Ocean, and the Pirates in

the Attempt happen to be overcome, the Captors

are not obliged to bring them to any Port, but

may exposs them immediately to Punishment, by

Hanging them at the Main-Yard: A sign of its

being of a very different and worse Nature than

any Crime committed upon the Land; for Robbers

and Murderers, and even Traytors themselves,

mayn’t be put to Death without passing a formal

Tryal: And if the fate of the Prisoner at the

Bar, with his Company, had allowed them to have

been overcome in their Piracies, &c. and

immediately hung up before the Sun, it had been

very just upon them. But being then suffered to

live, and now brought unto a Court of Justice,

they are to be used, treated, and tryed as the

Laws of England, and our own Country do

direct. (Arraignment, 5)

At this juncture, Dudley

cited Henry VIII’s 1536 Offences at Sea Act, after

which he mentioned that William Kidd had been the

last pirate tried under this statute, having been

transported to London to be tried in a court of law

in England. Then Dudley explained the reasoning

behind King William’s act before returning to the

current trial of Quelch.

It is by

Virtue of this Act of Parliament, and a

Commission pursuant thereto, that your

Excellency and this Honourable Court are now

Sitting in Judgment upon the Prisoner at the

Bar, and his vile Accomplices; and though it may

be thought by some a pretty severe thing, to put

an English-man to Death without a Jury, yet it

must be remembred, that the Wisdom and Justice

of our Nation, for very sufficient and excellent

Reasons, have so ordered it in the Case of

Piracy; a Crime, which . . . scarce deserved any

Law at all[.] (Arraignment, 6)

Then came the

all-important definition of piracy.

The

English Word Pirate, is derived from a Word that

signifies Roving, for Pirates, like Beasts of

Prey, are Seeking and Hunting upon the Ocean for

the Estates, and sometimes the Lives of the

Innocent Merchant and Mariner: His Character and

Description is thus: A Pirate is one who to

enrich himself, either by Surprize or open

Force, sets upon Merchants and others trading by

Sea, to spoil them of their Goods or Treasure,

and oftentimes sinking their Vessels, and

bereaving them of their Lives: And ’tis no

wonder if Piracy be reckon’d a much greater and

more pirnicious Crime, than Robbery upon the

Land, because the Consideration of the General

Navigation and Commerce of Nations, is far

beyond any Man’s particular Property: Besides,

whereas Robbery upon the Land is most commonly

from particular Persons; Piracy is from many,

and oftner attended with the Death of others[.]

(Arraignment, 6)

During the trial, the

attorney providing legal assistance to the pirates

raised some legal objections. One involved testimony

that gold dust

could not be identified as coming from a specific

place and an expert witness backed up this claim.

While the presiding judge agreed this was true, the

“Coin’d Gold shewn in Court . . . appear plainly to

be Portuguise,” and were permitted to be

admitted into evidence. (Arraignment, 13) During the trial, the

attorney providing legal assistance to the pirates

raised some legal objections. One involved testimony

that gold dust

could not be identified as coming from a specific

place and an expert witness backed up this claim.

While the presiding judge agreed this was true, the

“Coin’d Gold shewn in Court . . . appear plainly to

be Portuguise,” and were permitted to be

admitted into evidence. (Arraignment, 13)

When Meinzies pointed out that witnesses didn’t

always agree on places where prey was captured and

how many were on those ships at the time of

boarding, the judge called these differences “very

immaterial.” (Arraignment, 13)

Another objection concerned the charge against

Quelch for murdering a Portuguese master, even

though another man was identified as having done

that deed. To back up this point, Meinzies cited “Molloy

in his Chapter of Piracy.” In rebuttal, one of

the prosecutors pointed out that

the same

book says, That if the Common Law have

Jurisdiction of the cause, all that are present,

and assisting at such a Murder are principals.

Now the Statute 28. Henry VIII. makes

all Piracies, Robberies and Murders upon the

high Sea, Tryable according to the Rules of the

Common Law, as if they had been committed upon

the Land. (Arraignment, 13)

Therefore, even if Quelch

was not the killer, he was just as guilty because he

had been present when the crime was committed.

A more complicated, yet stronger, objection,

involved the fact “That the proceedings of this

Court, in Examining, Trying and Condemning

Pirates, shall be according to the Civil Law, and

the Methods and Rules of the Admiralty.” (Arraignment,

13)

Civil Law prohibited an accomplice from testifying

as “a Witness, being equally guilty with those he

accuses.” (Arraignment, 13) Meinzies cited

Sir Robert Wiseman’s The Law of Laws and Sir

Edward Coke’s Institutes of the Lawes of England

to support this.

At this point in time, the pirates who had turned

Queen’s Evidence had yet to be pardoned. (Therefore,

they were not impartial witnesses.) The Queen’s

Advocate pointed out that medieval law permitted

accomplice testimony under specific conditions,

calling such witnesses “approvers.” (What he did not

disclose was that doing so was considered mostly

obsolete in 1704, and that the guidelines under

which these particular accomplices would be

permitted to testify had not been met.) He also

pointed out that

in many

Cases, there happens to be no other way to bring

Criminals to their just Punishment, but by

singling out some of their Company, that may be

the least guilty, and make use of them to

convict the rest. (Arraignment, 14)

As for their not having

been officially pardoned yet, he added,

It has

never been thought convenient to give Approvers

their Pardon, until they have actually convicted

their accomplices, lest after their having their

Pardon they may refuse it; altho’ after they

have convicted those they approve, their Pardon

is ex Debito Justitić. This is the Opinion of my

Lord Coke, in his Pleas of the Crown,

and so has the practice been since. (Arraignment,

14).

It was clear that the

Court was going to prosecute the pirates and more

than likely find against them, but Meinzies was

determined to do what he could for his clients. He

tried one additional objection that spoke to an

ambiguity in English law. It involved the

contradiction between the statutes of Henry VIII and

William III. English trials were conducted under the

former, which allowed pirates “the benefit of a

Jury,” whereas William’s statute, which allowed for

pirate trials to be conducted in a vice-admiralty

court instead of England, also stipulated that no

jury would hear these cases.

Council to the Queen Thomas Newton kept mum on this

point, but Queen’s Advocate Dudley chose to evade

the issue.

As to the

Method of the Court of Admiralty, ’Tis now about

an Hundred and Three score Years since the

Statute of Henry VIII. was made; a term

long enough to make a Method of any Court, for

ever since that time with the Court of Admiralty

proceeded in cases of Piracy, according to the

Rules of the Common Law; and then as to that

other part of the New Statute, relating to

Piracy, That says, this Court is to proceed

according to the Civil Law. With submission, We

understand it to be the summary way of

proceeding by the Commissioners, and depriving

the Prisoner of a Jury; for ’tis most certain

that the late Statute against Piracy, doth

strengthen and establish the Statute of Henry

the VIII. And it would be very odd to suppose

that the first Act of Parliament in these cases

had rejected and condem’d, the method of the

civil Law in the trial of Pirates, &c. The

second Act of Parliament should be reconcil’d to

that Method, to restore and set it up in the

Plantations, especially when the Title of the

New Act, is an Act, for the more effectual

Suppression of Piracy, &c. (Arraignment,

14)

As Clifford Beal explains

in Quelch’s Gold, Newton

must have

known . . . that Meinzies was correct in his

summation. More disappointingly, Meinzies did

not press his objections further. He had done

only the bare minimum to raise the points on

behalf of his client; it would have been

detrimental in the extreme to his future career

to explode the case against Quelch and embarrass

the entire provincial government. (Beal,

159)

Six days after the trial

began, verdicts were announced. John Templeton was

found not guilty because of his age. William Whiting

was also cleared of the charges against him. The

remaining twenty-three pirates were deemed guilty of

the charges against them. On 30 June 1704, Quelch,

Lambert, Scudamore, Miller, Peterson, and Roach were

hanged. The other pirates spent the next year in

gaol before being pardoned.

Judge pronouncing sentence by

Pushkin and The Pirate's End by George Albert

Williams

(Sources: Shutterstock.com and

Dover's Pirates)

King William’s Act for the more effectual

Suppressions of Piracy was valid for seven

years.9

While in effect, this statute defined piracy as a

robbery committed upon the sea. What was unfortunate

was that it also included an expiration date. Once

1706 came and went, pirates had to be tried

according to Henry VIII’s 1536 statute, which

equated piracy with treason.

Not until 1717 would Parliament enact another law

that firmly identified piracy with robbery, making

it a crime of property. This statute, known as 4

George 1 c.11 or The Transportation Act, said this

about pirates:

all and

every person and persons who have committed or

shall commit any offence or offences, for which

they ought to be adjudged, deemed and taken to

be pirates, felons or robbers, by an act made in

the parliament holden in the eleventh and

twelfth years of the reign of his late majesty

King William the Third, intituled, An act for

the more effectual suppression of piracy, may be

tried and judged for every such offence in such

manner and form

as outlined in Henry

VIII’s 1536 statute. (Pickering, 475) Although that

reference included the taint of treason, its

inclusion here affirmed that the pirates would

suffer death rather than transport. This law also

dealt with those who could be considered accomplices

of pirates.

IV. And

whereas there are several persons who have secret

acquaintance with felons, and who make it their

business to help persons to their stolen goods,

and by that means gain money from them, which is

divided between them and the felons, whereby they

greatly encourage such offenders: be it

enacted . . . That where-ever any person taketh

money or reward, directly or indirectly, under

pretence or upon account of helping any person

or persons to any stolen goods or chattels,

every such person . . . shall be guilty of

felony, and suffer the pains and penalties of

felony, according to the nature of the felony

committed . . . as if such offender had himself

stolen such goods and chattels . . . . (Pickering,

473-474)

This guaranteed that

those who colluded with pirates and shared in the

profits would be just as guilty as the pirates and

therefore, be subject to the same penalties as those

accused of piracy. This statute also expanded the

definition of pirate: a pirate wasn’t just a thief

who conducted his business at sea; now he was also

anyone who assisted pirates. Additional laws against

piracy were enacted in 1721, 1739, and 1744, further

cementing the definition as a property crime instead

of a crime against the king.

Noted

jurist William Blackstone also

clarified the definition of piracy, as well as the

laws and punishments pertaining to this crime, in

his Commentaries on the Laws of England, which was

published between 1765 and 1769. Noted

jurist William Blackstone also

clarified the definition of piracy, as well as the

laws and punishments pertaining to this crime, in

his Commentaries on the Laws of England, which was

published between 1765 and 1769.

[T]he

crime of piracy, or robbery and depredation upon

the high seas, is an offense against the

universal law of society; a pirate being,

according to Sir Edward Coke, hostis humani

generis [enemy to mankind]. As therefore he has

renounced all the benefits of society and

government, and has reduced himself afresh to

the savage state of nature, by declaring war

against all mankind, all mankind must declare

war against him: so that every community has a

right, by the rule of self-defense, to inflict

that punishment upon him . . . .

[A]ny commander,

or other seafaring person, betraying his trust,

and running away with any ship, boat, ordnance,

ammunition, or goods; or yielding them up

voluntarily to a pirate; or conspiring to do

these acts; or any person confusing the

commander of a vessel, to hinder him from

fighting in defense of his ship, or to cause a

revolt on board; shall, for each of these

offenses, be adjudged a pirate, felon, and

robber, and shall suffer death, whether he be

principal or accessory. By the statute 8 Geo. I.

c. 24. the trading with known pirates, or

furnishing them with stores or ammunition, or

fitting out any vessel for that purpose, or in

any wise consulting, combining, confederating,

or corresponding with them; or the forcibly

boarding any merchant vessel, though without

seizing or carrying her off, and destroying or

throwing any of the goods overboard; shall be

deemed piracy: and all accessories to piracy,

are declared to be principal pirates, and felons

without benefit of clergy. (Blackstone)

To be continued . . .

Notes:

8. Although Quelch’s trial was

the first held in Colonial America per William’s

statute (permitting vice-admiralty courts to try

pirates), his was not the first pirate trial in the

colonies. Hanna mentions one that occurred in

Maryland in 1659; the sixteen accused were tried by

a grand jury. Found guilty of piracy, they were

evicted from the colony and told never to return.

9. Aside from identifying a

pirate as a thief, what set William’s law apart from

earlier statutes was that it also highlighted the

difference between a pirate and privateer. The

latter had a valid letter of marque, which meant it

was still viable and in effect at the time of the

plundering. If England was no longer at war or the

commission had expired, the privateers were now

considered pirates.

Resources (The list is so

extensive that I have placed it on a separate page.)

Copyright ©2025 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |