Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Merchant,

Pirate, Smuggler, Sea Lord

As students of history, we like facts:

birth year, birthplace, specific events,

et cetera. The past is rarely so

accommodating, especially for those of

humble beginnings. Our searches of

historical annals reveal early lives are

steeped in mystery or conflict and raise

more questions than they answer. This is

particularly true the further back in time

a person lives and when those records are

destroyed, either accidentally or to

eradicate the past. In the case of Zheng

Zhilong and his descendants, it is the

latter reason for the paucity because of

destruction wrought by authorities of the

Qing dynasty. Still, some traces of his

youth exist.

The first dilemma we face concerns his

name. Zheng Zhilong is how we refer to him

today, Zheng being his surname and Zhilong

his given name. (The name has also been

spelled Cheng Chi-lung in the past.) He is

also referred to as Yi-Guan, which means

“First Son,” a word that the Portuguese

wrote as Iquan. Japanese records list him

as Tei Shiryû or Tei Shiryū. Those written

by Europeans refer to him as Nicholas

Iquan, Nicolas Icoan, Nicholas Gaspard or

Jaspar, and Chinchillón.

His formal name was Zheng Zhilong, but no

record provides the name he used as a

child or young adult. When he reached the

age of twenty, he participated in a rite

of passage to mark his entry into

adulthood. In Imperial China it was rude

to call an adult by his given name unless

the speaker was of higher rank or an

elder. Instead, he would be addressed by a

courtesy (or style) name, which was deemed

a sign of respect. According to Shao

Tingcai (Shao T’ing-ts’ai), a historian

and philosopher who lived during the

seventeenth century, Zheng Zhilong’s

courtesy name was Fei Huang (Flying

Yellow), which came “from the Chinese

proverb feihuang tengda, “to make

rapid advances in one’s career.” (Antony,

Pirates, 113). Or his courtesy name

might have been Feihong (Flying Rainbow),

a name still associated with Zheng Zhilong

in 1640.

Within the pages of Taiwan

Wai zhi (also spelled Taiwan

waiji and written in the late

1660s), Jiang Risheng included the exact

date and time of Zheng Zhilong’s birth. He

was born between the hours of seven and

nine on the morning of 16 April 1604.

While many events included in this book

have been verified in other Chinese and

European documents, the writing is often a

mix of fact and fiction, much like what

Captain Johnson did in his General

History of the Pyrates in 1724.

While 1604 might be Zheng Zhilong’s true

birth year, a more probable time span

would be 1590-1610, and this might be

narrowed down further to 1592-1595.

His father was Zheng Shaozu (or Ziangyu or

Shibiao). He worked as a clerk at a grain

storehouse in the Quanzhou prefecture

(district). Ji Liuqi, who was born in 1622

and wrote about the Ming dynasty, believed

that Zheng men had worked as yamen

(government) clerks for several

generations.

Zheng Zhilong’s mother was Theyma (also

known as Lady Huang). She had two

brothers, one of whom was Huang Cheng, a

Macau trader who would play a significant

role in Zheng Zhilong’s later teenage

years.

He had three younger brothers (Bao the

Panther, Feng the Phoenix, and Hu the

Tiger) and three younger half-brothers

(Peng the Roc, Hú the Swan, and Guan the

Stork). It’s also possible that he had

some sisters as well.

Although Zheng Zhilong learned to read and

write before his seventh birthday, he was

never keen on his studies. He was

“good-looking, a skillful poet, a musician

of taste, a dancer of merit, and withal of

pleasing manners.” (Day, 27) He also liked

to box and practice martial arts. He

possessed charisma, charm, courage, and

guile. Instead of attending lessons, he

often prowled the streets, getting into

mischief or fighting, much to his father’s

chagrin. The pair had a contentious

relationship and, according to one

account, the elder Zheng harried his son

through the streets with a stick. Zheng

Zhilong’s only option was to board a ship

and sail to Macau around 1610.

The voyage took a week, but Zheng Zhilong

was not alone. Two of his brothers, Bao

and Hu, accompanied him. At the time,

Macau was one of the few places where the

Portuguese were permitted to trade with

China.

Macau

was an exotic place, a piece of

Portugal on the Chinese coast, with

plazas and priests and tolling bells.

An immense cathedral dominated the

hill in the middle of town, and

Japanese artisans were engraving its

stone façade, carving out ships,

lions, figures in long robes, winged

people playing horns. In one panel a

woman floats above a many-headed

serpent next to a caption that reads,

in Chinese, “Holy Mother stomps the

dragon head.” (Andrade, Lost, 22)

Ruins of Saint Paul's

Cathedral, built by the Jesuits from

1602 to 1640

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons, by No1lovesu)

The port was also the home of his maternal

uncle, Huang Cheng. He owned a trading

company and put his nephews to work. He

deemed education important, but felt

success and wealth were of greater value

than academic achievements. Zheng Zhilong

apparently agreed because he found his

skills more useful here than they had been

back home and he excelled at whatever he

set his hand to.

During his

time in Macau, he also met a Jesuit

priest, who befriended Zheng Zhilong and

taught him Portuguese. At some point

between 1615 and 1620, Zheng Zhilong was

baptized in the Catholic faith and became

Nicholas Iquan or Nicholas Iquan Gaspard

(or Jaspar). Whether he remained a devoted

Christian was debatable. Later in his

life, some Portuguese wrote, “[he] was so

impious, or so ignorant, that he equally

burnt incense to Jesus Christ and to his

idols.” (Andrade, Lost, 22) It was

also possible that he still attended mass

until he died. Certainly, he remained in

contact with Jesuits in his later years.

He wrote poems that he sent to Father

Francesco Sambiasi, and while living in

Beijing, he paid to have a house and

chapel built for the priests living in the

city. He also provided funds to them,

arranged for servants to work for them,

and purchased needed goods for their use.

During his final years, when he needed

help, they gave him “decem circiter

aureos,” a gift that “touched the

old man greatly and moved him to tears.” 1

(Vermote, 282) During his

time in Macau, he also met a Jesuit

priest, who befriended Zheng Zhilong and

taught him Portuguese. At some point

between 1615 and 1620, Zheng Zhilong was

baptized in the Catholic faith and became

Nicholas Iquan or Nicholas Iquan Gaspard

(or Jaspar). Whether he remained a devoted

Christian was debatable. Later in his

life, some Portuguese wrote, “[he] was so

impious, or so ignorant, that he equally

burnt incense to Jesus Christ and to his

idols.” (Andrade, Lost, 22) It was

also possible that he still attended mass

until he died. Certainly, he remained in

contact with Jesuits in his later years.

He wrote poems that he sent to Father

Francesco Sambiasi, and while living in

Beijing, he paid to have a house and

chapel built for the priests living in the

city. He also provided funds to them,

arranged for servants to work for them,

and purchased needed goods for their use.

During his final years, when he needed

help, they gave him “decem circiter

aureos,” a gift that “touched the

old man greatly and moved him to tears.” 1

(Vermote, 282)

Zheng Zhilong did many tasks for his

uncle, and when his uncle felt it was time

to test his knowledge and skills, his

uncle put him in charge of an illicit

cargo of “white sugar, calambak wood and

musk.” (Clements, 18) Zheng Zhilong

succeeded in delivering the goods to the

Japanese islands of Ryukyu. Eventually

Huang Cheng trusted Zheng Zhilong with

another important cargo, this one bound to

the port of Hirado, Japan. Here, he would

come in contact not only with the Japanese

but also men and ships from China, the

Dutch Republic, England, Portugal, and

Spain. It was also where he met pirates.

The moves to Macau and Hirado opened a

wider world for Zheng Zhilong, one in

which his charisma, charm, courage, and

guile would prove especially beneficial.

When winds of change blew across China, he

looked to the future, instead of dwelling

in the past. The path was rarely smooth

and required life skills not taught by

academic tutors. His journey of a thousand

miles permitted him to lay the foundation

upon a legacy that his son and grandson

would build.

Before and during Zheng

Zhilong’s lifetime, the Ming emperor

closed China’s borders to foreign trade

and prohibited his people from exporting

Chinese goods to outside ports. In places

where trade was vital, such as Fujian,

these sea bans had devastating effects.

The only way for many merchants and their

families to survive was to resort to

clandestine trade with foreigners. Such

activities often began with smuggling

goods from one location to another.

Initially, they encountered few problems,

but when imperial officials and forces

enforced the sea bans, or Westerners

wished to establish their own footholds in

Asian trade, the smugglers confronted

armed ships. To protect themselves, the

smugglers fortified their vessels with

weapons of their own. When permitted, they

traded legally. When trade was banned,

they plundered other vessels to acquire

desired goods. The incongruity of these

two sides of the coin resulted in a unique

class of piracy, the “merchant-pirates,”

and Zheng Zhilong would become an adept

among them. But first, he needed to

acquire the right skills and knowledge, as

well as suitable connections, and learn

how to combine all these to become an

entrepreneur. The first rung in this

ladder was working with his uncle in

Macao. The second rung was learning

Portuguese. The third rung was venturing

to places like the Ryukyu

Islands, which connected China and

Japan via Formosa, and was a base for

legitimate traders as well as smugglers

and pirates (known as the wakō).2

The fourth rung was reached when Zheng

Zhilong worked for the Vereenigde

Oostindische Compagnie (VOC,

Dutch East India Company), which

established their colonial trading post on

Formosa

(Taiwan). The fifth rung involved visits

to Japan, especially the port of Hirado.

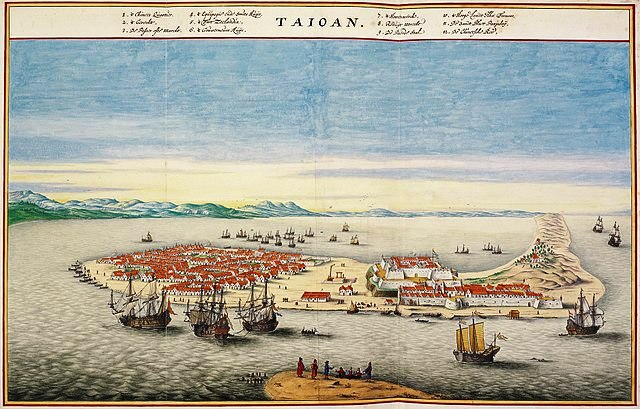

17th-century watercolor by Joan

Blaeu of Dutch colony of Fort Zeelandia on Formosa

17th-century watercolor by Joan

Blaeu of Dutch colony of Fort Zeelandia on Formosa

drawn no earlier than 1644. (Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

While in Japan, Zheng Zhilong met many

people who impacted his life in different

ways. Two men – Li

Dan and Yan Siqi – were traders from

China with significant wealth and

influence. Yan Siqi was a tailor who

realized that “life is as fleeting as the

morning dew,” according to the Taiwan

wai ji, and decided to become a

pirate instead. Little else is known about

him and some scholars are uncertain that

he ever existed.

Li Dan, on the other hand, was a Fujian

merchant, who once served as a slave

chained to the oars of a Spanish ship for

nine years. He was proficient at

identifying people who would be useful to

him, such as financial backers or

protectors (i.e., the Matsura

family who ruled Hirado), and those

he might easily deceive to gain what he

wanted.3

This allowed Li Dan to acquire ships and

create a trading network comprised of

merchants from a variety of cultures,

which permitted him to become the dominant

trader of Chinese goods in the early years

of the seventeenth century. After meeting

Zheng Zhilong, he invited the adventurous

and handsome lad to joined his enterprise,

and it didn’t take long for Zheng Zhilong

to become a favorite of Li Dan’s inner

circle.4

The knowledge he acquired from his mentor

and his associations with others, as well

as his natural talents and aptitude for

languages, gave him an edge. He

communicated effectively and reached

agreements with an eclectic group of

associates – Chinese, Dutch, Japanese,

Portuguese, and Spanish – that permitted

the Zheng clan to eventually dominate all

but ten percent of Chinese shipping for

sixty years.

His personal life also changed in Hirado

when he met the daughter of a low-ranking

samurai.

Tagawa Matsu was a young woman in her

early twenties. Whether he married her or

not is uncertain, but theirs was a true

love match.

In 1623, Li Dan offered Zheng Zhilong the

chance to become his agent in trade with

the Europeans. He also served as an

interpreter and entered into negotiations.

This required him to leave Hirado for the

Pescadores (Penghu Islands) in the Taiwan

Strait. Tagawa, who was pregnant, remained

in Japan.

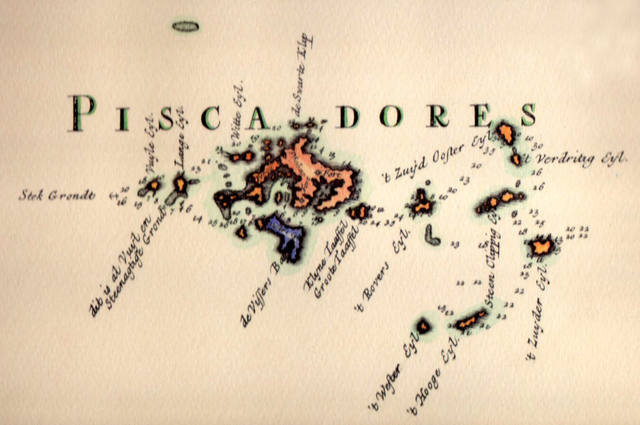

Pescadores Islands c. 1726 from map

drawn by J. van Braam and G. onder de Linden

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

The following year several key events took

place in Zheng Zhilong’s life. After his

return to Fujian, he married Lady Yan in

an extravagant ceremony.5

Back in Japan, Tagawa Matsu gave birth to

a son. Also noteworthy, his father, Zheng

Shaozu, died which made Zheng Zhilong the

head of the family. He moved his base of

operations to Amoy (Xiamen),

and soon seventeen of his “brothers”

worked on his fleet of junks. His network

of trade and piracy extended south to

Cambodia and northwest to Japan.

The Dutch were among those with whom Zheng

Zhilong traded. In October 1625, the

governor of Taiwan, Gerrit de Witt, wrote:

Here we are from day to day

expecting the man named Iquan, who

once served Commander Reijersen as

interpreter, to arrive leading twenty

to thirty junks, which are reported to

pillage the tribute ships or

transports the Chinese send up to the

north. (Clements, 56)

The following

year, he brought them porcelain and

agricultural products aboard nine ships.

The value of this cargo equaled 28,000 taels.6

One contract stipulated that he supply the

VOC with silk and sugar. These

commodities, which were measured in shi

or dan (pounds), totaled 9,000

shi. In exchange, he received an

unnamed amount of cash and 3,000 shi of

pepper.7

During the 1620s, at least ten others with

their own pirate junks vied for trade with

the foreigners. Zheng Zhilong got rid of

these rivals one by one. When the next

decade began, his power had grown

exponentially. According to one official,

Zheng was “a whale swallowing up the sea.”

(Antony, Like, 33). Shao Tingcai,

a seventeenth-century Qing scholar, wrote:

All merchant junks passing

through the South China Sea had to

have Zhilong’s safe-conduct pass.

Therefore, all of the outlaws and

rabble in the whole region pledged

allegiance to him and came under his

control. (Antony, Pirates,

113-114)

When dealing

with merchants, he instituted a baoshui,

where he basically forced them to give him

first right of refusal when it came to

purchasing their goods. (It’s also likely

that they allowed him to name his price

for those goods as well.) Despite such

extortion, the majority of people saw him

as a Robin Hood. Chaos reigned on land

from a series of revolts to severe drought

that caused famine, at times driving

people to commit acts of cannibalism.

Although he likely inflated the numbers,

Shao Tingcai wrote:

. . . there was a severe

famine in southern Fujian, Zhilong

seized several private merchant junks,

robbed them of their rice, and fed the

hungry famine victims. As a result,

his ranks swelled to several tens of

thousands. (Antony, Pirates,

113)8

Zheng Zhilong

also ferried many from China to Taiwan

where they could start life anew.

The Grand Coordinator of Fujian, Zhu

Yifeng, had another take on Zheng

Zhilong’s effective tactic. “The bandits

kill soldiers, but not the people; they

pillage the rich and give a small part [of

the booty] to the poor. [Thus,] their

power spreads.” (Calanca, 88)

What made Zheng Zhilong different from

other pirates and his predecessors were

his people skills and his ability to

isolate and exploit vulnerabilities in the

Ming military hierarchy. Two of these

involved the perfectly permissible raising

of biaobing, which was equivalent

to a personal armed force, and recruiting

warriors to protect the regions in which

they served. This is allowed him to create

his own paramilitary group, known as the

Zheng Bu (Zheng Ministry), in 1636. When

the Ming court selected him to govern

their fortress in Fujian four years later,

his generals in the Zheng Bu also received

official sanction and were posted to

command coastal forts.

As his dominance and influence grew, Zheng

Zhilong learned many lessons, one of which

was reinforced throughout his lifetime:

trust no one. Betrayals by family members

(including his own mother), and

high-ranking men within his maritime

organization (such as Li Kuiqi), and

agents representing the emperor (as would

occur when he aligned himself with the

Manchus after they established a new

dynasty in China), reinforced this lesson

time and again. It was one reason that he

surrounded himself with a special security

force that became known as the Black

Guard. Over time, he purchased and freed

around 500 Africans, originally enslaved

by the Portuguese. These men towered over

most Chinese and possessed exotic

appearances when compared to his

countrymen. They dressed in heavy armor

and flashy silk. When they joined in

battle, they screamed, “Santiago,” their

patron saint. Those horrific war cries

made enemies tremble.

Zheng Zhilong’s ties to the Dutch began

early in his career. Aside from

transacting trade with the VOC, he served

as a translator. Later, he became one of

their privateers, attacking Spanish

shipping bound to and from Manila in the

Philippines. One official felt Zheng

Zhilong was a better privateer than a

translator. In the 1640s, his business

ventures brought in yearly earnings akin

to or better than those of the VOC or even

England’s Honorable East India Company.

Needless to say, Zheng Zhilong’s interests

and those of the VOC did not always jibe.

They were more like rivals; both wanted

freer maritime trade than the Ming

government permitted, but they competed

for the same trade of imports and exports.

As a result, they were sometimes allies.

At other times, the Dutch formed

coalitions with other pirate fleets.

Zheng Zhilong’s fleet of warships were

larger and more powerful than those of the

Imperial navy. A governor-general of

provinces south of Fujian sent a note to

Beijing in which he wrote:

This pirate Zhilong is

extraordinarily cunning, practiced in

the art of sea warfare. His followers

are . . . more than thirty thousand in

total. His cannons are made by foreign

barbarians, and his warships are huge

and tall and meticulously made. When

they enter the water they never sink,

and when they encounter a reef they

never breach. His cannons are so

accurate and powerful that they can

strike at a distance of ten li and

immediately annihilate anything they

strike. (Andrade, Lost,

29)

This made his

junks the only ones that would be able to

effectively fight against a European

attack.

Despite all of

his wealth and power, Zheng Zhilong wanted

something he did not have. When a youth,

formal education and advancement in

Chinese society were not high on his to-do

list. He excelled in hands-on training and

real-world experiences more than rigorous

and tedious book learning and civil

examinations. Both of those were what

permitted men to be seen as honorable and

worthy. These were two traits that he

desired, and events in greater China were

about to provide him with that

possibility. Despite all of

his wealth and power, Zheng Zhilong wanted

something he did not have. When a youth,

formal education and advancement in

Chinese society were not high on his to-do

list. He excelled in hands-on training and

real-world experiences more than rigorous

and tedious book learning and civil

examinations. Both of those were what

permitted men to be seen as honorable and

worthy. These were two traits that he

desired, and events in greater China were

about to provide him with that

possibility.

Although the Ming dynasty ruled Manchuria,

their control over northeast China was

tenuous. As the Manchus

gained power there, the Ming emperor, his

councilors, and his officers neither

needed nor could afford to fight on two

fronts, so when members of the Quanzhou

aristocracy proposed that Zheng Zhilong be

offered a pardon, the emperor listened.

Now, it really wasn’t appropriate for him

to accept bandits into his government, but

if Zheng Zhilong’s pirates would disband,

the emperor was willing to forgive Zheng

Zhilong’s past indiscretions and give him

official standing within the Ming

government in Fujian. It would, of course,

be a provisional appointment, since he did

have to make amends. For the next three

years he was expected to go pirate hunting

and rid the seas of these marauders. When

the probationary period ended, he would

receive an official military rank.

Not all of the gentry agreed with this

plan; surely the emperor had heard the

rumors that quite a few government

officials in Fujian were on the pirate’s

payroll, and perhaps even within the royal

court. Perhaps so, but Zheng Zhilong

possessed what the emperor needed: men who

could fight; local connections; control of

the profitable trade between Fujian and

Taiwan; and fortified bases not only in

Amoy but also in other locations. With

pros outweighing cons, the emperor sent

Cai Shanzhi to see Zheng Zhilong in 1627.

Twenty-two years later, Juan de Palafox y

Mendoza wrote of this affair in his Historia

de la Conquista de la China por el

Tataro (The History of the

Conquest of China by the Tatars).

[B]eing informed of his

valour, the [Emperor] was desirous to

make use of his services in an affair

of high importance to the good and

welfare of his state, and therefore

offered Iquan a general pardon and

indemnity for all that was past . . .

And that he would not only receive him

into grace, but make him High Admiral

or Captain General of all the sea

coasts, give him the office of Great

Mandarin, and abundantly shower upon

him favours and rewards.

(Clements, 57)

Having long

sought honorable respect and prestige,

Zheng Zhilong agreed to the emperor’s

terms.

It just so happened that Zheng Zhilong’s

pirate fleet was one of two plaguing

China’s trade. The other belonged to

Xinsu, who received the same offer from

the emperor. The Ming hope was that the

two pirates would destroy each other, or

at the very least, get rid of one headache

and then the survivor, whose forces would

be weaker, would easily be taken care of

by the Imperial navy.

Although Zheng Zhilong accepted the Ming

offer, he did not immediately carry out

his assignment to get rid of Xinsu. He and

his brother, Hu the Tiger, disagreed about

whether they should work more closely with

the Chinese or the Dutch. Zheng Zhilong

favored the emperor, while Hu preferred

the latter, and they argued for months

over whose respect and recognition would

be of greater value to them. In the end,

Zheng Zhilong’s preference won out and

that is when his fleet sailed against

Xinsu. The Dutch were also on hand, but

came simply to watch the battle unfold.

Palafox wrote, “the courage and conduct of

Iquan quickly gained him the victory,

which he secured by leaping into his

enemy’s ship and with his own hand killing

[Xinsu], and cutting off his head.”

(Clements, 58)

Contrary to what was hoped, the battle did

not weaken Zheng Zhilong. Nor were Ming

officials keen on adhering to the original

agreement; they felt that his power and

sphere of influence had increased to such

an extent that no enemy would or could

oppose him. A major sticking point was the

size of his empire. They wanted him to

downsize. He, however, expected the

emperor to follow through on his offer. A

Fujian official, He Qiaoyuan, was tasked

with trying to get Zheng Zhilong to see

things from the emperor’s perspective.

All your feelings are well

known . . . You do repent of your

behaviour; you do not want to murder

and plunder the people of the

countryside. All people know this. But

of [your] more than ten thousand

followers, why don’t they understand

your feelings? Some of them just want

to fill their mouths and warm their

bodies, others are fortune seekers . .

. Now that you have so many followers

like this, all of them being poor or

bad people, runaway soldiers or

criminals, they behave obsequiously

towards you and become your followers,

and make you ‘The Great King of the

Sea.’ You also enjoy having this

reputation and like to live up to it.

(Clements, 58)

Weeks passed.

Words were exchanged. Finally, Zheng

Zhilong agreed “that his men would no

longer cause clamor, and would be

progressively dispersed.” (Clements, 59)

Going forward, he was to continue to hunt

pirates, specifically those who had once

followed Captain Li Dan but never

acknowledged Zheng Zhilong as his

successor, as a further show of good

faith. The following year, he was

appointed as an imperial admiral and

charged with patrolling the seas.

Not everyone in the Zheng clan or within

Zheng Zhilong’s network was pleased with

his decision to surrender. Chen Zhijing,

his godbrother, convinced a man named

Zhong Bin to double-cross Zheng Zhilong

and attack the Chongwu

fortress. He learned of this

proposed betrayal and seized his

godbrother.

Nor was he the only one to commit

treachery against Zheng Zhilong. An

influential advisor within his

organization did so and was slain. One of

his valued commanders, a man named Li

Kuiqi, absconded with the majority of the

Zheng fleet and men, and seized Xiamen.

Having lost one of his strongholds and

without sufficient vessels to pursue the

turncoat, Zheng Zhilong and one of his

brothers visited Anhai and nearby fishing

villages to cobble together a ramshackle

fleet of fifty vessels and persuaded

fishermen to serve as mercenaries.

Even though the enemy was three times

their size and those crews were skilled

fighters, Zheng Zhilong set sail. Despite

these overwhelming odds, he was counting

on one thing that Li Kuiqi apparently

forgot to initially consider. Among the

crews of the usurped war junks were many

of Zheng’s relatives and their loyalty was

to him first. When the light dawned on Li

Kuiqi that his ships carried enemies as

well as friends, he gathered up all of

those loyal to Zheng Zhilong and executed

them. Learning of this, Zheng retreated

but kept his substitute force at the ready

and trained the crews to fight. When the

opportunity presented itself and Li Kiqui

was away from Xiamen for a brief time,

Zheng Zhilong took the turncoat’s family

hostage.

Whilst this transpired, discord grew among

Li Kuiqi’s officers. One of these

captains, who hailed from Gangzhou, sent

word to Zheng Zhilong that when the moment

was right, he was willing to change sides.

This was good news, but Zheng Zhilong

would need more to vanquish the snake. He

sought help from his network of friends in

Japan, one of whom was now governor

general of Batavia. Jacques

Specx agreed to lend Zheng a few

Dutch ships to bring down Li Kuiqi. In

February 1630, Zheng’s new fleet and the

heavily-armed Dutch approached Li Kuiqi.

The Gangzhou captain and his men joined

Zheng, and together the three forces

demolished Li Kuiqi and his fleet off the

island of Nan’ao.

The survivors formed a new band of

pirates, led by Liu Xiang. In 1633, they

struck Zheng Zhilong’s home base of Anhai

and slew several members of his family. A

series of battles ensued that came to be

known as “the Fujian navy’s seven great

victories.” (Lu, 141) By the fifth battle,

Liu Xiang’s fleet was showing severe signs

of wear and tear and was not nearly as

powerful as Zheng Zhilong’s. Even so, Liu

Xiang won because he had forced Portuguese

and Dutch captives to man his guns. The

final confrontation took place off the

coast of Guangdong, where Liu Xiang was

slain during the battle. An unknown number

of survivors fled to the northern border

of Fujian, where Chen Peng (Zheng

Zhilong’s most indispensable warrior)

obliterated them. The rest of the pirates

surrendered to Zheng Zhilong.

One Dutchman who was at

odds with Zheng Zhilong was Hans

Putmans, the new governor of Taiwan.

He felt Zheng was not living up to

expectations regarding wider trade with

China. He did not have permission to grant

the Dutchman’s demands, but Putmans

apparently did not or would not see this.

Zheng Zhilong could merely pave the way by

speaking with the new governor of Fujian,

Zou Weilian.

Zou Weilian had passed all the civil

service examinations and had been elevated

from provincial positions to national

ones, a rarity among Chinese mandarins.

When he came to Fujian in 1632, he did so

with express orders from the emperor to

resolve the problems with the Dutch and

the pirates. From his perspective the only

way to get rid of one was to get rid of

the other. He once wrote that “I’ve

observed that since ancient times, when

Chinese and barbarians mix together, all

kinds of troubles result.” (Andrade, Lost,

32)

The more Putmans dealt with the Chinese,

the more he considered them to be

“deceitful, treacherous, untrustworthy,

craven.” (Andrade, Lost, 33)

In a single word, they were prevaricators.

Therefore, he decided to use them to his

advantage. Since Chinese sailors earned no

more than four tael per annum at most, it

might behoove him to pay them to fight

their own people. The cost would be

minimal from his perspective because the VOC

paid their crews nearly ten times as much

as what the Chinese received, and whatever

booty was captured would finance their

share. To that end, he sent out dispatches

to Chinese sailors to join him in a new

venture that would pit them against Zheng

Zhilong. Some accepted his proposal.

When ready, Putmans set sail for Xiamen.

His fleet consisted of nine Dutch

ships, which Ming scholars described

as being

three hundred feet long,

sixty feet wide, and more than two

feet thick. They have five masts, and

behind them they have a three-story

tower. On the sides are small ports

where they place brass cannons. And

underneath the masts they have huge

twenty-foot-long iron cannons, which,

when fired, can blast holes into and

destroy stone walls, their thunder

resounding for ten miles (several

dozen li). (Andrade, Lost,

36)

Zou Weilian’s

description of these combination merchant

and fighting vessels was similar.

[T]he red-haired barbarians

have ships that are five hundred feet

long and seventy feet wide. They’re

called decked-ships because within

them they have three layers, all of

which have huge cannons facing

outwards that can pierce and split

stone walls, their thunder sounding

for ten miles. . . . The Hollanders’

ability to ravage the sea is based on

this technology. Our own ships, when

confronting Dutch ships, are smashed

into powder. (Andrade, Lost 36)

Dutch ships circa early

17th century

(Oil painting by Andries van Eertvelt,

1610-1620, of the second expedition to

the East Indies returning to Amsterdam

in 1599)

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

At the time, Zheng Zhilong had shipwrights

building new ships for him, and thirty of

these were based on these Dutch designs.

Each had two gun decks capable of carrying

up to thirty-six large guns on

European-style gun carriages with the

requisite cabling to prevent the guns from

becoming loose cannons and wreaking havoc.

Putmans led his fleet of nine ships to the

far side of Gulangyu, where they anchored

away from prying eyes. At dawn, the fleet

separated into two forces and approached

the harbor from different directions. The

Chinese believed the Dutch were friendly,

so they put up no resistance. The

intruders opened fire. Those aboard the

junks abandoned ship and swam ashore.

Rather than waste gunpowder and shot,

Putmans had his men hack and burn the

Chinese vessels, which provided the Dutch

with no plunder other than fifty iron guns

and firewood. Only three of Zheng

Zhilong’s vessels survived the attack. One

Dutchman died in the assault because he

caught fire while torching one of the

Chinese ships.

Zheng Zhilong’s response, housed within

VOC archives, was a mix of shock and

anger.

You’ve behaved like a

pirate! Are you proud of yourself?

Attacking without warning . . .? If

you had told me in advance, I would

have come out like a soldier and

fought openly, and whoever won would

have deserved the victory, but I

thought you had come as a friend, to

trade and do business. I’ll bide my

time. Don’t believe that you and your

forces will be allowed to remain here

in the imperial waterways for long.

(Andrade, Lost, 42)

Putmans didn’t

take the threat seriously and continued

pillaging like a pirate. The Chinese were

unable to stop him because their vessels

“are tall and large, while ours are low

and small, so we can’t attack them from

below like that.” (Andrade, Lost,

43) He garnered a wide assortment of booty

from watermelons to lacquer tables, from

deerskins to cloves. One haul from a

vessel returning from the Philippines

netted him 27,994 pieces of eight (roughly

$8,128,437 in 2023). All told, the Dutch

reckoned they captured cargo valued at

64,017.25 pieces of eight ($17,611,614).

Plunder taken was a dividend rather than

Putmans’s endgame. He just wanted to put

the Chinese out of action and force them

to give into his demand of free trade for

the Dutch with China. To his way of

thinking Zheng Zhilong was afraid;

certainly, quite a few pirates felt that

might be true, because by the time October

came, 450 sailed with the Dutch.

What Putmans didn’t realize was that his

actions had forced two opposing forces

(Zheng Zhilong and Zou Weilian) to form

their own alliance. They set aside their

differences to stop the Dutch. Shipwrights

returned to shipyards to reconstruct Zheng

Zhilong’s new fleet. Zou Weilian mustered

military leaders to bring arms of all

sizes. Together, these disparate forces

vowed to fight to the death.

While Putmans was out plundering, Zheng

Zhilong was waging his own version of

subterfuge, teasing him with the

possibility of compromise. Then he sent

another missive, this one very different

in tone.

How can a dog be permitted

to lay its bitch head on the emperor’s

pillow? . . . If you want to fight,

bring it to us here in Xiamen, where

the high officials of China can watch

our victory over you. (Andrade, Lost,

45)

The signatures

of twenty-one commanders appeared at the

end of the letter. Putmans was offended

and considered it more swagger than a real

threat. Still his fleet sailed to Liaolua

Bay, and all the vessels flew blue flags

bearing the letters VOC.

Early the next morning an odd assortment

of 150 vessels approached. They belonged

to Zheng Zhilong, who wrote:

It was just daybreak when

we saw the barbarians’ decked ships .

. . nine of them, cocky and self

satisfied with the cliffs at their

back, accompanied by fifty pirate

ships sailing back and forth around

them. (Andrade, Lost, 47)

But this

approaching eclectic armada was not what

Putmans expected. He saw what Zhilong

wanted him to see.

[T]hey were extremely well

supplied with guns and men, and they

comported themselves bravely and

without fear, so we concluded that

these were all warjunks and therefore

expected that – with God’s help – we

would be victorious. . . .

The

Chinese came forth like insane,

forsaken, crazy, desperate men, who

had already given up their lives,

showing no fear of any violence of

cannons, muskets, fire, or flame. (Andrade,

Lost, 47-48)

And then it was

too late. Two opposing vessels slammed

into each other and “went up in an instant

in such terrifying tall flames, burning so

vehemently, that it seemed nearly

impossible.” (Andrade, Lost, 48)

When the flames reached the magazine where

the gunpowder was stored, the vessels

exploded, killing Dutch and Chinese alike.

Despite the conflagration, the Chinese

soldiers didn’t stop with just the one

ship. They boarded another and clashed in

hand-to-hand combat, driven by the promise

that if they seized this second vessel,

they would receive accolades of the

highest order. More vessels came together

and the flames spread.

Zheng Zhilong described the scene.

When the decked ships were

burning, the fire and smoke soared up

to the heavens, and our eyes were

filled with the sight of floating

corpses, while the bodies of those who

were captured and beheaded piled up in

heaps. (Andrade, Lost, 49)

The truth

finally dawned on Putmans.

[T]his entire fleet had

been prepared as fireships and they’d

had no intention of doing battle,

planning instead to come up against us

and set fire to our ships. This was

despite the fact that these were

well-armed and large vessels, the very

best warjunks. We had no chance of

victory since they enjoyed odds of

twenty against one and didn’t care

about their own lives. (Andrade, Lost,

49)

Putmans’s flag

ship fled. Zheng Zhilong pursued. But fate

intervened with “wild” “sea wind” and

“rough and treacherous” “waves.” (Andrade,

Lost, 49)

When a final tally was taken, Putmans lost

four of his nine ships. Ninety-three men

were gone, although how many of those died

or were taken prisoner is unknown. Among

the prizes Zheng Zhilong took were “six

large cannons, two little cannons, sixteen

muskets, eleven barbarian swords, one iron

helmet, six tubes of gunpowder, seven

barbarian books, one sea chart, three

suits of armor.” (Andrade, Lost,

50) His captives included Chinese pirates,

two of their wives, and an undefined

number of Japanese pirates. The emperor

and his court considered this win a

“miracle at sea.” From Zheng Zhilong’s

perspective,

[i]t seems that this

victory is enough to reestablish the

prestige and authority of China, and,

in contrast, to lower the spirits of

those crafty barbarians. (Andrade,

Lost, 50)

The strange

bedfellows that brought about this victory

proved particularly rewarding to Zheng

Zhilong. He could still use the Dutch, and

Ming officials felt he was the only person

capable of managing them. Therefore, why

did he need Zou Weilian around to get in

his way?

He took Zou Weilian’s place as governor,

and once free to continue as he deemed

best, Zheng Zhilong resumed trading with

the Dutch. Mostly he sent his ships to

Taiwan, rather than allowing their ships

to come to him. He decided how much silk

they could purchase and told them how much

it would cost.

During his time as admiral, Zheng Zhilong

taxed ship cargoes at forty percent and

insisted that ships pay for protection.

The latter was the only way to avoid being

plundered by pirates. In exchange for the

extorted sum of 3,000 in gold, merchant

captains received a flag emblazoned with

the Chinese character “Zheng” (Serious).

Few ship owners refused to pay. Ships also

had to pay tolls, and when combined with

the taxes (or extortion fees), these

proved quite profitable. The tolls his men

collected equated to around 10,000,000

taels per annum. His trade with Japan and

Southeast Asia garnered two to three times

that amount. Add to that what he took in

from rents and other land resources, as

well as bribes, and his annual income

probably surpassed that of the VOC three

or four times over.

Around this time, Zheng built a new home

in Anping, north of the island of Jinmen

on the mainland and south of Quanzhou. The

opulent palace was surrounded by a

three-mile outer wall. Guards walked along

parapets of the compound to protect the

interior and his family. The garden

included fountains, ponds with fish,

pavilions, tea-houses, and a small zoo of

exotic animals. “A canal led directly to

his personal residence, and it was said

that it even stretched to his own bedroom

so he could board a ship at a moment’s

notice.” (Andrade, Lost, 53) He also had a

private chapel in which he displayed the

Catholic crucifix and various statues of

Chinese deities. When all was ready, Zheng

Zhilong summoned his seven-year-old son,

often called Lucky Pine, to come live with

him. His mother, Tagawa, remained in

Japan. When Lucky Pine arrived, Zheng

Zhilong embraced this son whom he had

never seen and called him Zheng Sen

(Forest). Each evening, the young boy

“would face east and look to his mother,

hiding his tears.” (Clements, 72)

Zheng Zhilong wished for his first love to

join him. She had not come with their son

because the Japanese were not permitted to

leave their country. So, in 1646, Zhilong

sought permission from the authorities of

the Tokugawa shogunate to allow Tagawa

Matsu to emigrate. Permission was granted,

but she was forced to leave behind another

son.

In June 1644, the Manchu

invaders captured Beijing and established

the Qing dynasty.9

Initially, the Zheng clan pledged

allegiance to the Ming dynasty and vowed

to see the rightful emperor restored to

the throne. Rather than allow the Manchus

to capture him, the Ming emperor committed

suicide near the end of April. While the

Qing ruled from Beijing, the Ming

established a southern

dynasty. The first of these, the Hongguang

emperor, was captured in 1646 and

executed in Beijing. He was succeeded by

the Longwu

emperor, who sought refuge in Fujian

province. Whether Zheng Zhilong decided to

be proactive or thought his best chances

of survival lay with the Qing

court, he negotiated with their

representatives and changed sides,

retaining his position of power in Fujian.

This allowed the Manchus to capture the

province, as well as the Longwu emperor

who was taken and slain in October.

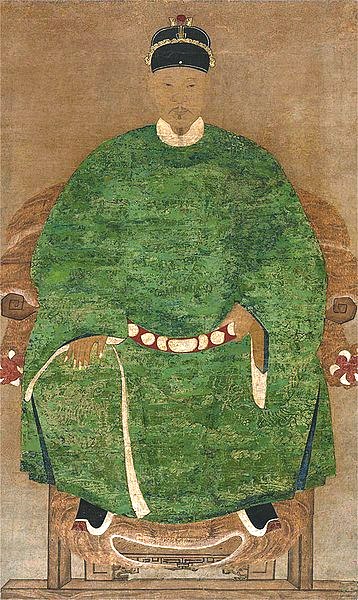

Left: Hongguang

Emperor, also known as Zhu Yousong, by unknown

artist (Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

Left: Hongguang

Emperor, also known as Zhu Yousong, by unknown

artist (Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

Right: Longwu Emperor, also known as Zhu Yujian,

by unknown artist (Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

As the Manchus swept through Fujian, they

also captured Quanzhou, where Tagawa Matsu

lived. Some accounts say that they ravaged

her and afterward, she committed suicide.

Or perhaps she took her own life to

prevent herself from falling into their

clutches. No matter which was true, her

death had a profound impact on her son.

The Zheng Bu ceased to

exist after this. Some of its generals

joined the Southern Ming emperor’s

government. Others became local military

commanders. Those who remained fully loyal

to the Zheng

clan joined Zheng

Chenggong, who assumed leadership of

his father’s organization. Unlike his

father, he remained loyal to the Ming

dynasty, and eventually was honored with a

name that meant “Lord with the Imperial

Surname,” which Europeans translated to

Koxinga (also spelled Coxinga). The Zheng Bu ceased to

exist after this. Some of its generals

joined the Southern Ming emperor’s

government. Others became local military

commanders. Those who remained fully loyal

to the Zheng

clan joined Zheng

Chenggong, who assumed leadership of

his father’s organization. Unlike his

father, he remained loyal to the Ming

dynasty, and eventually was honored with a

name that meant “Lord with the Imperial

Surname,” which Europeans translated to

Koxinga (also spelled Coxinga).

Unfortunately for Zheng Zhilong, the Qing

court did not keep their promises to him

for long. Prince Bolo distrusted him,

believing that he was double dealing,

playing one side against the other, for

his own advantage. Prince Bolo ordered him

to be placed in chains and escorted to

Beijing. A Franciscan friar described his

capture in a letter.

The prince and lord of this

city of Anhai, of these ports and

frontiers, is the mandarin who is

called Yquam [Iquan], whose beginnings

were in making himself feared by the

power he had at sea. He, because of

the fear which the Tartar King [the

Qing emperor] had of him, was summoned

and taken by design to the court of

Beijing, where he is detained, he

being given hope that he will be sent

back to his lands and will be given

absolute rule over this province of

Fujian, that of Guangdong, and another

which adjoins them. Pending his

return, this city and these ports are

governed by the same people whom he

left in charge, which are in this city

of Anhai a mannish woman, his

stepmother [una varonil mujer, su

madrastra], in a related port his

brother, another [brother] in Amoy

[Xiamen], and in his lands a son of

his who now with more than one hundred

thousand men is at sea to make war

against the Tartars if they do not

release his father. (Wills, 124)

The Qing court

held Zheng Zhilong in Beijing under house

arrest. His accommodations befitted those

of a prince, but he was kept away from

most of his family. Despite his seclusion,

he still conducted business and made new

friends, including local Jesuit priests.

He even provided money for them to build a

new church.

Thinking they might better control him and

through him, his son, Qing emissaries

persuaded Zheng Zhilong to bring his son

into their fold. In fact, if he brought

the rest of the Zheng clan over to their

side, he would be released. He and his son

exchanged letters. In his second one,

Zheng Zhilong wrote:

The Manchu court offers

territory in exchange for peace. They

wish to send two noblemen to present

you with the title and deeds of the

Dukedom of Haicheng, allowing your

followers to abide in the region.

(Clements, 149) 10

But Zheng

Chenggong had learned well from his

father. He did not trust the Manchus, and

he had no intention of forsaking the Ming

emperor.

Two years later, Zheng Zhilong wrote

another letter, but this one was not at

the behest of his jailers. His words were

meant only for his son, and the missive

was to be smuggled out of the city by

those who still supported the Zheng clan.

What Zhilong wrote and how the document

ended up in Manchu hands remains unknown,

but the contents were sufficient to

abruptly end the Qing emperor’s efforts to

bring Zheng Chenggong into the fold. Zheng

Zhilong was divested of all his titles and

thrown in prison with other members of his

family, including one of his sons and Bao

the Panther, his brother. He was also

sentenced to die, but that judgement was

not carried out immediately.

When the first Qing emperor

died of smallpox in February 1661, his

third son became the Kangxi

Emperor. He was only seven years

old, so Manchu members of the royal court,

who had also served his father, acted as

regents. They decided it was time to carry

out Zheng Zhilong’s sentence, announcing

on 24 November that he would endure lingchi.

This ritualistic death by a thousand cuts

involved single cuts in a specific order:

“fleshy parts – thighs, calves, and

breasts – were dealt with first, followed

by appendages such as the nose, ears,

fingers and toes.” With surgical skill the

executioner dismembered the convicted

piece by piece, ending “the butchery by

stabbing the man through the heart, and

decapitating him.” (Abbott, 381) When the first Qing emperor

died of smallpox in February 1661, his

third son became the Kangxi

Emperor. He was only seven years

old, so Manchu members of the royal court,

who had also served his father, acted as

regents. They decided it was time to carry

out Zheng Zhilong’s sentence, announcing

on 24 November that he would endure lingchi.

This ritualistic death by a thousand cuts

involved single cuts in a specific order:

“fleshy parts – thighs, calves, and

breasts – were dealt with first, followed

by appendages such as the nose, ears,

fingers and toes.” With surgical skill the

executioner dismembered the convicted

piece by piece, ending “the butchery by

stabbing the man through the heart, and

decapitating him.” (Abbott, 381)

Thomas Taylor Meadows wrote of witnessing

such an execution in 1851. The

executioner

proceeded, with a single-edged dagger

or knife, to cut up the man on the

cross: whose sole clothing consisted

of his wide trousers, rolled down to

his hips and up to his buttocks. He

was a strongly-made man, above the

middle-size, and apparently about

forty years of age. . . . we observed

the two cuts across the forehead, the

cutting off of the left breast, and

slicing of the flesh from the front of

the thighs . . . From the first stroke

of the knife till the moment the body

was cut down from the cross and

decapitated, about four or five

minutes elapsed. (Meadows,

655-656)

To make Zheng

Zhilong’s execution more gut-wrenching, he

would first have to watch two sons and

eight others undergo this form of torture

first. When the execution day arrived, the

Qing court altered their pronouncement;

instead of dying by lingchi, Zheng Zhilong

and the others would be decapitated.

Afterwards, all of the Zheng family’s

property and wealth was seized, and their

ancestral graves destroyed. To make Zheng

Zhilong’s execution more gut-wrenching, he

would first have to watch two sons and

eight others undergo this form of torture

first. When the execution day arrived, the

Qing court altered their pronouncement;

instead of dying by lingchi, Zheng Zhilong

and the others would be decapitated.

Afterwards, all of the Zheng family’s

property and wealth was seized, and their

ancestral graves destroyed.

During his lifetime, Zheng Zhilong

mastered many skills and finessed many

people in his climb from obscurity to the

lofty realms of a sea lord. He was canny

and had a knack for military tactics. If

his enemy thought him in front of them, in

reality he was behind them. He began

writing a strategy handbook entitled Jing

guo xionglue (Grand Strategy for

Ordering the Country) while in Japan in

1612. (The original twenty chapters were a

gift for the founder of the Tokugawa

Shogunate.) This handbook became a

work-in-progress that had reached eighty

chapters in 1645.

Father Vittorio Riccio, a Dominican

missionary and contemporary of both Zheng

Zhilong and his son, said of the former:

Nicolas the apostate, a

marvel of human fate, who rose up by

most despicable chance to challenge

kings and emperors. (Ho, 263)

Notes:

1. Although the Latin

words translate to ten gold coins in gold,

it is more likely that the Jesuits gave

Zheng Zhilong ten silver taels. At the

time, one of these coins would be enough

to purchase more than 166 pounds of flour.

2. Wakō,

referring to where the pirates originated

rather than their race, are often thought

of as Japanese. In reality, they were

Chinese.

3. The Matsura ruled

Hirado from 1603 to 1868, but their roots

there trace back to 794. Prior to Tokugawa

Ieyasu gaining control over all of Japan

and establishing the Tokugawa Shogunate,

the Matsura supported a different leader.

To show that they now supported the new

shogunate, the head of the Matsura torched

his new castle

in 1613. Eventually, the family gained

high standing within the Tokugawa

Shogunate during the seventeenth century.

4. It’s possible that

Zheng Zhilong delved into piracy early in

his sea career. In 1622, there were three

pirate leaders operating out of Fujian,

China: Yang Lu, Cai Wu, and Zhong Bu. The

latter two got into a scuffle with naval

commander Yu Zigan. He won; Cai Wu fled to

Japan and Zhong Bu lurked around Taiwan.

This defeat gave Yang Lu greater power;

the pirates giving their allegiance to him

numbered 3,000 and they served aboard

seventy-two junks. Zheng Zhilong, a

small-fry among the unallied pirates,

offered to join Yang Lu, but he refused.

This might be how he came to join Li Dan’s

organization.

5. Lady Yan was the

daughter of one of Li Dan’s associates.

She would give Zheng Zhilong four sons:

Shixi, Shidu, Shiyin, and Shi’en.

He also had two daughters (mother unknown)

who were raised in the Catholic faith. One

would marry a Portuguese man named Antonio

Rodrigues, whose father had ties with

Zheng Zhilong on Anhai.

6. Tael was a

means for measuring silver in China. It

was recorded in accounting ledgers to show

the amount of a transaction and what it

was worth. Payments were made in actual

silver or foreign currency, depending on

whether the trade was made in China or

transacted with outlanders. The actual

measure of a tael varied because

there was no uniformity in scales and

regions, but according to Encyclopedia

Britannica “most were

equivalent to 1.3 ounces of silver.”

7. China’s first

emperor, Shi Huang Di, unified basic

measurements after he came to power in 221

BCE. The shi or dan was

a measurement of weight and was equivalent

to the weight a man could tote around on a

shoulder pole. During the Ming dynasty,

one shi was equal to 100 jin

and 1 jin has been equated to

590 grams in the metric system of weights,

which did not exist during the Ming

dynasty. Thus, 3,000 shi =

300,000 jin = 177,000,000 grams.

9,000 shi = 900,000 jin =

531,000,000 grams.

8. Among his many

lieutenants (commanders of his junks) were

his younger brothers Bao the Panther and

Hu the Tiger and his half-brother Peng the

Roc. In addition to blood relatives, Zheng

Zhilong often adopted the offspring of the

poor and destitute, whom he raised to

become viable members of his crews. One of

these boys was named Zheng Tai, a sullen

and stubborn lad whose own family showed

him no respect. Zheng Zhilong took him

under his wing, and Zheng Tai rose through

the ranks and outlived many of those who

thought he would never amount to anything.

9. Once Beijing fell,

war would be waged for four decades before

the Qing dynasty gained complete control

of China.

10. This passage is a

summarized version of Zheng Zhilong’s

words and were recorded in Yang Ying’s Xian

Wang Shi Lu Jiao Zhu (Notes on the

Records of the First Kings) around 1661.

Resources:

Abbott, Geoffrey. “Thousand

Cuts,” The Book of Execution: An

Encyclopedia of Methods of Judicial

Execution. Headline, 1994,

380-383.

Andrade, Tonio. Lost Colony: The

Untold Story of China’s First Great

Victory over the West. Princeton

University, 2011.

Andrade, Tonio, and Hang Xing. "The East

Asian Maritime Realm in Global History,

1500-1700," Sea Rovers, Silver, and

Samaurai, 1500-1700 edited by

Tonio Andrade and Hang Xing. University

of Hawai'i, 2019, 1-27.

Antony,

Robert J. “Introduction: The Shadowy

World of the Greater China Seas,” Elusive

Pirates, Pervasive Smugglers: Violence

and Clandestine Trade in the Greater

China Seas edited by Robert J.

Antony. Hong Kong University, 2010,

1-14.

Antony, Robert J. Like Froth

Floating on the Sea: The World of

Pirates and Seafarers in Late Imperial

South China. Institute of East

Asian Studies, University of California,

2003.

Antony,

Robert J. Pirates in the Age of Sail.

W. W. Norton & Co., 2007.

Blusé, Leonard. “Shame and Scandal in

the Family: Dutch Eavesdropping in the

Zheng Lineage,” Sea Rovers, Silver,

and Samurai: Maritime East Asia in

Global History, 1550-1700 edited

by Tonio Andrade and Hang Xing.

University of Hawai’i, 2019, 226-237.

Calanca, Paola. “Piracy and Coastal

Security in Southeastern China,

1600-1780” in Elusive Pirates,

Pervasive Smugglers: Violence and

Clandestine Trade in the Greater China

Seas edited by Robert J. Antony.

Hong Kong University, 2010, 85-98.

Carioti, Patrizia. “The Zheng Regime and

the Tokugawa Bakufu: Asking for Japanese

Interventions,” Sea Rovers, Silver,

and Samurai: Maritime East Asia in

Global History, 1550-1700 edited

by Tonio Andrade and Hang Xing.

University of Hawai’i, 2019, 156-180.

Carter, James. “China’s

Great Pirate, Zheng Zhilong, Takes on

the Dutch,” The China Project (20

October 2021).

Chinese

Names – Rules, Meanings, Taboos, and

Classic Examples. Chinese

Fetching.

Chinese

Weights and Measures. Chinasage.

Clements, Jonathan. Coxinga and the

Fall of the Ming Dynasty. Sutton,

2005.

“The

Company’s Chinese Pirates: How the

Dutch East India Company Tried to Lead a

Coalition of Pirates to War against

China, 1621-1662,” History

Cooperative.

Day, A. Grove. Pirates of the

Pacific. Meredith Press, 1968.

Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period

(1644-1912) edited by Arthur W.

Hummel. United States Government

Printing Office, 1944, II: 638-639.

Emmer, Pieter C., and Joseph J. L.

Gommans. The Dutch Overseas Empire,

1600-1800 translated by Marilyn

Hedges. Cambridge University, 2021.

Hang Xing. Conflict and Commerce in

Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family

and the Shaping of the Modern World,

c. 1620-1720. Cambridge

University, 2017.

Harris, Lane J. “Terms

of Measurement, Units of Currency, and

Bureaucratic Titles,” The

Peking Gazette: A Reader in

Nineteenth-Century Chinese History.

Brill, 2018.

Ho, Daphon David. “The Burning Shore:

Fujian and the Coastal Depopulation,

1661-1683,” Sea Rovers, Silver, and

Samurai: Maritime East Asia in Global

History, 1550-1700 edited by Tonio

Andrade and Hang Xing. University of

Hawai’i, 2019, 260-289.

Konstam, Angus. Piracy: The Complete

History. Osprey, 2008.

Laver, Michael. “Neither Here

nor There: Trade, Piracy, and the

‘Space Between’ in Early Modern East

Asia,” Sea Rovers, Silver, and

Samurai: Maritime East Asia in

Global History, 1550-1700 edited

by Tonio Andrade and Hang Xing.

University of Hawai’i, 2019, 28-37.

Lu Cheng-heng. “Between Bureaucrats

and Bandits: The Rise of Zheng Zhilong

and His Organization, the Zheng

Ministry (Z Bu),” Sea

Rovers, Silver, and Samaurai: Maritime

East Asia in Global History, 1550-1700 edited by

Tonio Andrade and Hang Xing.

University of Hawai’i, 2019, 132-155.

Meadows, Thomas Taylor. The

Chinese and Their Rebellions.

Academic Reprints, 1856, 655-656.

Piracy

in Historical Asia.

Crossroads Research Centre. 2022.

Shapinsky, Peter D. “Envoys and Escorts:

Representation and Performance among

Koxinga’s Japanese Pirate Ancestors,” Sea

Rovers, Silver, and Samurai: Maritime

East Asia in Global History, 1550-1700

edited by Tonio Andrade and Hang Xing.

University of Hawai’i, 2019, 38-64.

Shapinsky, Peter D. “From Sea Bandits to

Sea Lords: Nonstate Violence and Pirate

Identities in Fifteenth- and

Sixteenth-Century Japan” in Elusive

Pirates, Pervasive Smugglers: Violence

and Clandestine Trade in the Greater

China Seas edited by Robert J.

Antony. Hong Kong University, 2010,

27-41.

Smits, Gregory. “Rethinking

Early Ryukyuan History,” The

Asia-Pacific Journal 17:7:1 (1

April 2019).

Theobald, Ulrich. Duliangheng,

weights and measures.

ChinaKnowledge.de.

Turnball, Stephen. Pirate of the Far

East 811-1639. Osprey, 2007.

Vermote, Frederick. “The Role of Urban

Real Estate in Jesuit Finances and

Networks between Europe and China,

1612-1778.” PhD diss., The University of

British Columbia, Vancouver, 2013.

Wills, Jr., John E. “Yiguan’s

Origins: Clues from Chinese, Japanese,

Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, and Latin

Sources,” Sea

Rovers, Silver, and Samaurai: Maritime

East Asia in Global History, 1550-1700 edited by

Tonio Andrade and Hang Xing.

University of Hawai’i, 2019, 114-131.

Xu Ke. “Piracy, Seaborne Trade and the

Rivalries of Foreign Sea Powers in

East and Southeast Asia, 1511 to 1839:

A Chinese Perspective,” Piracy,

Maritime Terrorism and Securing the

Malacca Straits edited by Graham

Gerard Ong-Webb. International

Institute for Asian Studies and

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies,

2006, 221-240.

Copyright ©2023 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |