Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Stede Bonnet (continued)

Rules Shouldn’t Be

Broken

The norm

among pirates was to band together and

“earn” their wages by seizing other

vessels to garner shares of the plunder

taken. This wasn’t what Stede Bonnet chose

to do. Instead, he paid his men wages.1

After he and his hired crew set sail from

Barbados, they went hunting. One might

think they had little chance of success,

but some of his 126 men knew enough to

guide their captain toward potential prey.

As they sailed northward along the eastern

seaboard of Britain’s North American

colonies, they captured at least four

vessels, including Anne, Turbet,

Endeavour, and Young. From

these prizes, the pirates seized

“Provisions, Clothes, Money, Ammunition,

etc.” (Moss, Life, 16) The norm

among pirates was to band together and

“earn” their wages by seizing other

vessels to garner shares of the plunder

taken. This wasn’t what Stede Bonnet chose

to do. Instead, he paid his men wages.1

After he and his hired crew set sail from

Barbados, they went hunting. One might

think they had little chance of success,

but some of his 126 men knew enough to

guide their captain toward potential prey.

As they sailed northward along the eastern

seaboard of Britain’s North American

colonies, they captured at least four

vessels, including Anne, Turbet,

Endeavour, and Young. From

these prizes, the pirates seized

“Provisions, Clothes, Money, Ammunition,

etc.” (Moss, Life, 16)

From the pirates’ perspective, this was

good. Stede’s reaction wasn’t quite the

same. Why? It just so happened that Turbet

hailed from his hometown (Bridgetown,

Barbados). That meant the possibility of

recognition. Whether his intentions were

to return home one day with no one the

wiser about his misdeeds, or he didn’t

wish his nefarious activities to reflect

poorly on his family, he did not wish

others to know his true identity. (Which

was why he insisted that his crew call him

“Captain Edwards.”) In snaring Turbet,

there was a good chance that one of the

captives might recognize him, or if he

permitted them to sail away with their

vessel, someone on Barbados might put two

and two together and figure out the truth.

No, he couldn’t allow that to happen.

Whereas Anne, Endeavour,

and Young were permitted to be on

their merry way, Turbet was set

aflame. Thereafter, the pirates went

hunting anew, going as far north as New

York before sailing south again.

Stede succeeded in keeping his identity a

secret as much as he knew how to navigate.

(In other words, he failed miserably.) By

the time they reached Charles Town

(present-day Charleston, South Carolina)

in August, the authorities already knew

the truth. In fact, Captain Bartholomew

Candler of HMS Winchelsea made

sure they knew.

. . . lately on the Coast a

Pirate Sloop from Barbados Command by

one Major Bonnett [Bonnet], who has an

Estate in that Island and the Sloop is

his Own, this Advice I had by Letter

from thence, that in April last [1717]

He ran away out of Carlisle Bay in the

night he had aboard 126 men 6 Guns

& Arms & Ammunition Enough[.]

(Moss, 22)

Whether Stede

knew of this or not, he was determined to

prey on ships entering and leaving the

city. He didn’t have long to wait either.

A brigantine, captained by Thomas Porter,

was the first to fall into his trap. As

soon as he saw their black flag, Porter

hauled down his own and grudgingly allowed

the pirates to ransack his ship. What they

found didn’t amount to much in monetary

terms, but Stede refused to allow the

brigantine to continue on her way. If he

released them, Porter was certain to

report to the authorities the minute he

docked in Charles Town, which would ruin

any chance the pirates had of garnering

more booty to place in Revenge’s

hold.

1711 inset of Charles

Town from A Compleat

description of the province of

Carolina in 3 parts,

published by Edward Crisp,

London. (Source: Library of

Congress)

The strategy worked, for soon after,

Captain Joseph Palmer’s sloop was taken.

This time, the pirates found sugar,

slaves, and rum – all worthy commodities

as far as they were concerned. Stede was

happy that his men were satisfied with

their haul, but he faced a dilemma.

Palmer, too, was from Barbados, and he and

his men recognized Stede. The only thing

to do, from his perspective, was to take

all the captives and their ships and seek

a temporary haven.

Cape Fear River provided just the spot,

and the pirates took advantage of it to

careen Revenge. Once their work

was finished and all their plunder was

stowed, they herded the captives onto

Porter’s brigantine, torched Palmer’s

sloop, and freed them, albeit with only a

small portion of the rigging and sails

needed for the brigantine to go anywhere.

Her speed was so limited, it took the

captains and their men four weeks to reach

Charles Town; they arrived there on 17

September 1717. Naturally, the captains

headed straight to the governor to warn

him.

As for the pirates, they had a decision to

make. Only they couldn’t agree on where

their next hunting grounds should be. So

they sailed for the Straits of Florida.

That’s where lookouts spotted a much

bigger vessel flying Spanish colors. Now,

pirates had an unwritten rule of thumb: if

the potential prey is bigger than you,

avoid her like the plague. Thinking her to

be a merchant ship and allowing his

previous successes to go to his head,

Stede ignored this wisdom. After all, it

was common knowledge that many merchant

ships carried Quaker guns. (These

“weapons” were actually made of wood and

painted black to look like the real

thing.) Except the guns this ship carried

weren’t fake. Nor was she a merchant ship.

She was a warship with greater firepower

and her captain knew exactly what to do.

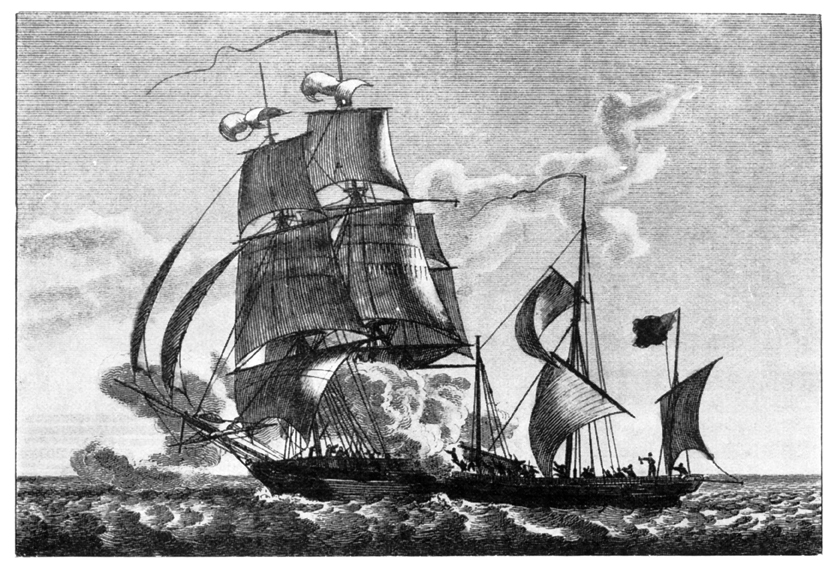

When Revenge

sailed parallel to the Spanish ship,

her captain ordered his men to unleash a

broadside at the pirates. Then he

positioned his vessel so it sailed across

Revenge’s stern. Many pirates fell

from the sweeping broadside, including

Stede. Others were killed or injured when

the stern was hit. Those who survived

these attacks had one priority – get away

from the Spaniards as soon as possible. When Revenge

sailed parallel to the Spanish ship,

her captain ordered his men to unleash a

broadside at the pirates. Then he

positioned his vessel so it sailed across

Revenge’s stern. Many pirates fell

from the sweeping broadside, including

Stede. Others were killed or injured when

the stern was hit. Those who survived

these attacks had one priority – get away

from the Spaniards as soon as possible.

Once clear, a tally was taken. Thirty to

forty of their comrades had fallen. Stede

was unconscious and taken below to what

remained of his cabin. The shots had

smashed through glass and wood, decimating

furniture and anything else in their path.

His precious books were scattered all

about the deck. Once he regained

consciousness, Stede did not stray from

his cabin until after the much-damaged Revenge

reached New

Providence in the Bahamas.

A decade earlier, John Graves published a

treatise about New Providence, where he

had once had the unenviable job of

collecting customs. He believed the island

would make an ideal “Shelter

for Pyrates, if left without good

Government and some Strength.” He added

that it would only take “one small Pyrat

with Fifty Men that are acquainted with

the Inhabitants” to “Ruin the Place[.]”

(Fictum) By 1714, his prognostication had

come true. Three years later, the pirates

were firmly entrenched in Nassau, and one

of them was a man named Edward

Thache (Blackbeard).

Enlarged segment of

"An exact draught of the island of

New Providence

one of the islands in the Bahamas

West Indies," 17--. (Source: Library of

Congress)

Whether he and Stede were previously

acquainted – Thache did have ties to

Barbados – or perhaps he was just curious

about this strange captain who enjoyed

reading and had the gumption to attack

Spanish men-of-war, or he desired a second

ship (he already had “a sloop 6 guns and

about 70 men”), he persuaded Stede to turn

over command of Revenge to him.

(Marley, 789) In exchange, Thache would

teach him what he needed to know to be a

pirate captain. To Stede’s way of

thinking, what could be better? He would

add to his repertoire of knowledge as

regards sailing and pirating without the

burden of command, and he could do so at

his leisure. In the meantime, his cabin

would remain his domicile, where he could

read to his heart’s content and take as

long as he deemed necessary to recuperate.

While

Thache oversaw repairs, he also improved Revenge’s

armament by adding two more guns and

signing on more men. When they departed

New Providence, his crew numbered 150.

Their ultimate destination was Delaware

Bay, but there were plenty of prey to

capture along the way. In short shrift,

they plundered fifteen vessels. James

Logan, chief steward of William

Penn’s colony and a Philadelphia merchant,

made mention of these seizures on 24

October 1717. While

Thache oversaw repairs, he also improved Revenge’s

armament by adding two more guns and

signing on more men. When they departed

New Providence, his crew numbered 150.

Their ultimate destination was Delaware

Bay, but there were plenty of prey to

capture along the way. In short shrift,

they plundered fifteen vessels. James

Logan, chief steward of William

Penn’s colony and a Philadelphia merchant,

made mention of these seizures on 24

October 1717.

We have been very much

disturbed this last week by the

Pirates They have taken and plundered

Six or Seven Vessels bound out or into

this river Some they have destroyed

Some they have taken to Their own use

& Some they have dismissed after

Plunder.

. . .

The Sloop

that came on our Coast had about 130

Men all Stout Fellows all English

without any mixture Double armed they

waited they Said for their Consort a

Ship of 26 Guns to whom when joyned

they designed to Visit Philadia,

Some of our Mastr Say They

know almost every man aboard most of

them having been lately in this River,

their Comandr is one Teach

who was here a Mate from Jamia

about 2 yr ago. (Logan)

One master who

docked in Philadelphia reported the

seizure of his ship on 24 October 1717,

and the incident was reprinted on page two

of the Boston

News-Letter.

He was taken about 12

days since off our Capes by a Pirate

Sloop called the Revenge, of 12 Guns

150 Men, Commanded by one Teach . . .

They have Arms to fire five rounds

before they load again.

(Philadelphia)

The pirates

tossed most of the cargo found in the hold

overboard. Two additional snows, whose

cargo also went by the board, were

captured and one joined the fleet of

pirate vessels. From a sloop, captained by

Peter Peters,

they took 27 Pipes of

Wine, cut his Masts by the Board,

after which She drove ashore and

Stranded. (Philadelphia, 2)

Another

provided them with “two Pipes of Wine”

before the pirates sank her.

(Philadelphia, 2) Loose-lipped pirates,

whether accidentally or on purpose, “told

the Prisoners that they expected a Consort

Ship of 30 Guns, and then they would go up

into Philadelphia, others of them said

they were bound to the Capes of Virginia .

. . .” (Philadelphia, 2)

These captives also made mention of Stede.

On board the Pirate Sloop

is Major Bennet, but has no Command,

he walks about in his Morning Gown,

and then to his Books, of which he has

a good Library on Board, he was not

well of his wounds that he received by

attacking of a Spanish Man of War, who

kill’d and wounded him 30 or 40 Men.

(Philadelphia, 2)

(Think about

it. Had Stede not broken the rule about

going after larger ships, he wouldn’t have

suffered such a disabling wound. He might

have been in a better frame of mind to

fully understand that in giving Thache

command of Revenge, Stede lost his

ship and crew. He would not, as he would

later claim, have felt himself “a

prisoner” for nearly a year.)

Vengeance Is Mine

Edward Thache’s depredations

continued. Additional confirmation of

Stede being in league with him, although

no details of their arrangement were

provided, came in a letter to the

Admiralty, dated 4 December 1717. Captain

Ellis Brand of HMS Lyme wrote:

Since my Arrival in

Virginia I have heard but of one pyrot

sloop, that was run away with, from

Barbadoes commanded by Maj[o]r

Bonnett, but now is commanded by one

Teach, Bonnet being suspended from his

command, but is still on board, they

have most infested the Capes of

delaware and sometimes of Bermudas,

never continuing forty eight hours in

one place, he is now gone to the

So[uth]ward. (Moss, 49)

What Brand

might not have known was that Thache

had snared quite a ship a few weeks

earlier. On 17 November, La

Concorde had the misfortune of

crossing his path and he did not hesitate.

Aside from the ship, which would be

renamed Queen

Anne’s Revenge (QAR),

the pirates acquired bags of gold dust,

and two carpenters, a caulker, a cook,

three doctors, a gunsmith, and a navigator

were forced to join Thache’s crew. Since

Stede had recovered from his wounds, he

resumed command of Revenge because

Thache quit the sloop in favor of the

ship.2

Model

of Balckbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge

in the North Carolina Museum of History by

Qualiesin, 2020 (Source: Wikipedia

Commons)

The marauding continued, with Stede and

Thache sailing in consort. On 6 January

1718, Walter Hamilton, governor of the

Leeward Islands, wrote:

. . . we did see another

pirate ship and a large sloop which we

were informed when we came off of the

Island St. Eustatius by a sloop sent

express from St. Christopher’s were

two other pirates that had two days

before taken some of the trading

sloops off of that Island and sunk a

ship loaden with white sugar etc. . .

. The ship is commanded by one

Captain Teatch, the sloop by one Major

Bonnett an inhabitant of Barbadoes,

some say Bonnett commands both ship

and sloop. . . . The ship some say has

22 others say she has 26 guns mounted

but all agree that she can carry 40

and is full of men the sloop hath ten

guns and doth not want men.

(America, Jan. 6. 298.)

HMS Seaford

and HMS Scarborough went

seeking the pirates, but their search

proved fruitless. Probably because they

were looking in the wrong places. The

pirates were off the island of Rattan (Roatán)

near Honduras, more than a thousand miles

distant.

Since Thache wanted to careen his new

flagship, Stede opted to go hunting on his

own. Which is when he happened upon a

potential prize. Perhaps he had forgotten

the painful lesson of attacking a larger

ship. Perhaps he wanted to outshine

Thache, because if he successfully

captured the Protestant Caesar,

Stede would command a vessel larger than

Thache’s. Or perhaps he just wanted to

prove that the lessons he learned while

sailing with Thache had stuck. Whatever

his motivation, Stede chose to attack the

400-ton merchantman even though she was

about four times larger than Revenge and

she carried sixteen more guns than Revenge’s

ten.

Captain Wyer, master of the Protestant

Caesar (PC) had no intention

of surrendering his ship and fifty men.

[O]n the 28th of March last

about 120 Leagues to the Westward of

Jamaica, near the Latitidue 16. off

the Island Rattan, espyed a large

Sloop which he supposed to be a

Pirate, and put his Ship in order to

Fight her, which said Sloop had 10

Guns and upwards of 50 Men, and about

nine a Clock at Night came under Capt.

Wyers Stern, and fired several Cannon

in upon the said Ship and a Volley of

small Shot, unto which he returned two

of his Stern Chase Guns, and a like

Volley of small Shot, upon which the

Sloop’s Company hail’d him in English,

telling him that if he fired another

Gun they would give him no Quarter,

but Capt. Wyer continued Fighting them

till twelve a Clock at Night, when she

left the Ship . . . . (Boston, 16

June 1718, 2)

Having fled

under the cover of darkness, Revenge headed

to Turneffe (off the coast of Belize) to

make repairs. They reached the lagoon on 2

April 1718, only to find another ship

anchored there. While Stede’s men might

have rejoiced at seeing the QAR,

his reaction was probably far different.

The Revenges had tired of being shot up

unnecessarily and not gaining the wealth

they desired. They petitioned Thache to

address this situation. His solution was

to replace Revenge’s captain.

Stede was out and a man named Richards was

in. According to Captain Johnson, Thache

took the Major on aboard

his own Ship, telling him, that as he

had not been used to the Fatigues and

Care of such a Post, it would be

better for him to decline it, and live

easy and at his Pleasure, in such a

Ship as his, where he should not be

obliged to perform Duty, but follow

his own Inclinations. (Johnson,

71)

To say that

Thache was less than pleased with how

Stede handled the incident with the PC

would probably be an understatement.

Thache had nurtured a well-honed

reputation, and “surrender” was not in his

vocabulary. This matter needed to be

rectified, but before he was ready to

sail, Adventure sailed right into

his hands. A gunner aboard the QAR fired

a warning shot across the eighty-ton

sloop’s bow. Facing two pirate ships, Adventure’s

master, David Herriot, had little choice.

Five pirates came aboard and helped him

maneuver the boat close to QAR,

where the anchor was dropped.

Nor was this the only sloop that found

herself a victim of piracy. The Land

of Promise fell to the pirates a

short time later and Thache told her

master, Thomas Newton, “that he was, bound

to the Bay of Hunduras to Burn the Ship Protestant

Caesar . . . that Wyer might not

brag when he went to New England that he

had beat a Pirate.” (Boston, 16 June 1718,

2)

It was payback time, and this time

vengeance would be Thache’s, not the

Lord’s.

After Captain Wyer and his men had fended

off Revenge, they got busy loading

PC with “about 50 Tuns of

Logwood.” (Boston, 16 June 1718, 2)

European manufacturers of ink, furniture,

and dye prized this wood, making it a

lucrative trade; Spain, on the other hand,

considered all the logwood their property

and were keen on stopping outsiders from

“stealing” it. Which was why, when

lookouts aboard PC noticed five

vessels sailing toward them, they

initially assumed these strangers carried

Spaniards. Then the ship and the largest

of the four sloops hoisted “Black Flags

and Deaths Heads in them” while the three

smaller sloops flew “Bloody Flags.”

(Boston, 16 June 1718, 2)

Capt. Wyer judging them to

be Pirates, call’d his Officers and

Men up on Deck asking them if they

would stand by him and defend the

Ship, they answered, if they were

Spaniards they would stand by him as

long as they had Life, but if they

were Pirates they would not Fight, and

thereupon Capt. Wyer sent out his

second Mate with his Pinnace to

discover who they were and finding the

Ship had 40 Guns 300 Men called the Queen

Ann’s Revenge, Commanded by Edward

Teach a Pirate, and they found the

Sloop was the same that they Fought

the 28th of March last, Capt. Wyers

Men all declared they would not Fight

and quitted the Ship believing they

would be Murthered by the Sloops

Company, and so all went on Shore.

(Boston, 16 June 1718, 2)

This

made easy pickings for the pirates. Three

days after the capture, This

made easy pickings for the pirates. Three

days after the capture,

Capt. Teach the Pirate sent

word on shore to Capt. Wyer, that if

he came on Board he would do him no

hurt, accordingly he went on Board

Teach’s Ship, who told him he was glad

that he left his Ship, else his Men on

Board his Sloop would have done him

Damage for Fighting with them; and

said he would burn his Ship because

she belonged to Boston, adding he

would burn all Vessels belonging to

New England for Executing the six

Pirates at Boston.3

And on the 12th of the said April

Capt. Wyer saw the Pirates go on Board

of his Ship, who set her on Fire and

Burnt her with the Wood. (Boston,

16 June 1718, 2)

On 31 May 1718,

Bermuda’s lieutenant governor wrote a

letter to the Council of Trade and

Plantations. Thache’s flotilla was quite

impressive, not to mention dangerous. The

QAR possessed “36 guns and 300

men,” while Revenge’s numbers were

“12 guns and 115 men.” On top of these,

there were “two other ships, in all which,

it is computed there are 700 men or

thereabt.” (America, May 31. Bermuda.

551.)

With such a formidable force, it was only

a matter of time before Bonnet, Thache,

and their men made a statement profound

enough to force authorities to take

action. This occurred in June 1718. The

target this time was the port of Charles

Town, South Carolina. While lying in wait

for about a week, according to David

Herriot, a captive turned pirate,

Thatch and Richards took

a Ship commanded by one Robert

Clark, bound from Charles-Town

aforesaid to London. Says, He

has heard by the Pirates there were

both Goods and Money taken out of the

said Clark’s Ship, but knows

not the Particulars, this Deponent

being then on board his own Sloop.

. . .

whilst they lay off the Bar of

Charles-Town, took another Vessel

. . . two Pinks . . . a Brigantine

with Negroes . . . and after

detaining them for some few Days, they

let them go again. (Information

of David, 45)

From Herriot’s

perspective, this was just another day. To

the citizens of Charles Town and the

victims who found themselves captives,

this was another thing entirely. Governor

Johnson wrote to the Council of

Trade and Plantations:

The unspeakable calamity

this poor Province suffers from pyrats

obliges me to inform your Lordships of

it . . . about 14 days ago 4 sail of

them appeared in sight of the Town

tooke our pilot boat and after wards 8

or 9 sail wth. severall of the best

inhabitants of this place on board and

then sent me word if I did not

imediately send them a chest of

medicins they would put every prisoner

to death which for there sakes being

complied with after plundering them of

all they had were sent ashore almost

naked. (America, June 18. 556.)

Eventually,

vengeance would become that of the pirate

hunters. This type of daring could not go

unpunished. But Thache still had a trick

up his sleeve, and Stede would not be

happy when he discovered it.

Temptation

After their successful blockade of

Charles Town, the pirates escaped all the

hue and cry. Thache had a plan, although

few were privy to his intentions. David

Herriot, the former master of Adventure

who was captured and turned pirate,

was not one of those few. After his

arrest, he told authorities of the

flotilla’s arrival at Topsail Inlet in the

Outer Banks of North Carolina six days

later.

. . . having then

under their Command the said Ship Queen

Anne’s Revenge, the Sloop

commanded by Richards, this

Deponent’s Sloop, commanded by one

Capt. Hands, one of

the said Pirate Crew, and a

small empty Sloop . . . they had all

got safe into Topsail-Inlet, except Thatch, the said

Thatch’s Ship Queen Anne’s

Revenge run

a-ground off of the Bar of Topsail-Inlet, and the

said Thatch sent his

Quarter-Master to command this

Deponent’s Sloop to come to his

Assistance; but she run a-ground

likewise about Gun-shot from the said

Thatch, before

his said Sloop could come to their

Assistance, and both the said Thatch’s Ship and

this Deponent’s Sloop were wreck’d;

and the said Thatch and all the

other Sloop’s Companies went on board

the Revenge . . . and

on board the other Sloop . . . . . . . having then

under their Command the said Ship Queen

Anne’s Revenge, the Sloop

commanded by Richards, this

Deponent’s Sloop, commanded by one

Capt. Hands, one of

the said Pirate Crew, and a

small empty Sloop . . . they had all

got safe into Topsail-Inlet, except Thatch, the said

Thatch’s Ship Queen Anne’s

Revenge run

a-ground off of the Bar of Topsail-Inlet, and the

said Thatch sent his

Quarter-Master to command this

Deponent’s Sloop to come to his

Assistance; but she run a-ground

likewise about Gun-shot from the said

Thatch, before

his said Sloop could come to their

Assistance, and both the said Thatch’s Ship and

this Deponent’s Sloop were wreck’d;

and the said Thatch and all the

other Sloop’s Companies went on board

the Revenge . . . and

on board the other Sloop . . . .

Says,

’Twas generally believed the said Thatch

run his Vessel a-ground on purpose to

break up the Companies, and to secure

what Moneys and Effects he had got for

himself and such other of them as he

had most Value for. (Information

of David, 45-46)

Another man

Thache did not include within his secret

cadre was Stede. Instead, he was tasked

with securing pardons for the pirates from

Charles

Eden, the governor of North

Carolina.

The previous

September the front page of The London

Gazette printed a notice from

Whitehall, dated 15 September.

Complaint having been

made to His Majesty, by great Numbers

of Merchants, Masters of Ships, and

others, as well as by the several

Governours of His Majesty’s Islands

and Plantations in the West-Indies,

that the Pirates are grown so numerous

that they infest not only the Seas

near Jamaica, but even those of the

Northern Continent of America; and

that unless some effectual Means be

used, the whole Trade from Great

Britain to those Parts will not only

be obstructed, but in imminent Danger

[of] being lost: His Majesty has, upon

mature Deliberation in Council, been

graciously pleased . . . to order a

proper Force to be employed for

suppressing the said Piracies . . . . Complaint having been

made to His Majesty, by great Numbers

of Merchants, Masters of Ships, and

others, as well as by the several

Governours of His Majesty’s Islands

and Plantations in the West-Indies,

that the Pirates are grown so numerous

that they infest not only the Seas

near Jamaica, but even those of the

Northern Continent of America; and

that unless some effectual Means be

used, the whole Trade from Great

Britain to those Parts will not only

be obstructed, but in imminent Danger

[of] being lost: His Majesty has, upon

mature Deliberation in Council, been

graciously pleased . . . to order a

proper Force to be employed for

suppressing the said Piracies . . . .

And that

nothing may be wanting for the more

effectually putting an End to the said

Piracies, His Majesty has also been

graciously pleased to issue the

following Proclamation. (London,

1)

That decree

spelled out the terms for securing a

pardon, one with a deadline.

. . . we do hereby promise

and declare, that in case any of the

said Pirates shall, on or before the

fifth Day of September, in the Year of

our Lord One thousand seven hundred

and eighteen, surrender him or

themselves to . . . any Governour . .

. of any of our Plantations or

Dominions . . . shall have our

gracious Pardon . . . . . (London,

1)

(Now, it’s

important to note that the only piratical

acts being forgiven were those committed

“before the fifth Day of January next

ensuing.” (London, 1) This meant

that piratical acts committed prior to 5

January 1718 were forgivable, but any

plundering taking place after that date

was not.)

Stede successfully secured his pardon. Now

that he was no longer a criminal, what

should a former pirate do? The obvious

answer was to go home, make amends, and

resume his old life. Or if that didn’t

appeal, perhaps he could start life anew

elsewhere and become an upstanding citizen

again. But . . . temptation reared its

ugly head. Since England and the Dutch

Republic were now at war with Spain,

he could continue his marauding legally.4

He just needed a letter of marque and a

crew.

He expected Thache and the others to join

him in this venture, but when he returned

to Topsail Inlet, he found Adventure and

the QAR stripped clean and abandoned.

Thache was nowhere to be found and

seventeen men were marooned. One of these

was David Herriot, who explained in his

deposition what had occurred during

Stede’s absence. He

requested the said Thatch

to let him have a Boat, and a few

Hands, to go to some inhabited Place

in North Carolina, or to Virginia . .

. and desired the said Thatch to make

this Deponent some Satisfaction for

his said Sloop: Both which said Thatch

promised to do. But instead thereof,

ordered this Deponent, with about

sixteen more, to be put on shore on a

small Sandy Hill or Bank, a League

distant from the Main; on which Place

there was no Inhabitant, nor

Provisions. (Information of David,

46)

Herriot and his

comrades spent “two Nights and one Day”

marooned on this island. (Information of

David, 46) They totally expected to die

there since Thache had also taken the boat

used to transport them ashore.

Stede’s current mode of transportation was

insufficient to rescue the marooned men.

He ventured over to the wrecks where

luckily, he found that Thache had left Revenge

unharmed. Stede “reassumed the Command

of his Vessel” and retrieved Herriot and

the others from the island. When they were

all together, Stede shared his plans about

going to Saint Thomas to “take a

Commission against the Spaniards . . . and

that he would give this Deponent his

Passage thither, but could not pay him any

Wages . . . .” (Information of David, 46)

Herriot felt that fair, as did the others,

and so they set sail aboard Revenge.

There were just two problems with their

current predicament. No one had any money

since Thache had taken it all for himself

and his closest cohorts, and without

money, they could not purchase the

necessary supplies to get them to St.

Thomas. Temptation, of course, provided a

simple solution. The easiest way to obtain

what was needed was to revert to their old

ways, with a slight twist. For example,

while in Virginia waters, they seized “ten

or twelve Barrels of Pork, and about four

hundred Weight of Bread.” In return, they

gave those on the pink “eight or ten Cask

of Rice, and one old Cable.” (Information

of David, 46) Not exactly a fair trade,

but in the eyes of Stede and his men, it

was legal to trade one set of goods for

another. Stede just conveniently forgot

that trade meant that both parties were

desirous of the exchange. That was not the

case this time or any other instance where

he employed this tactic. Just ask the

master of a fifty-ton sloop that they

stopped. He had to swap “twenty Barrels of

Pork, some small Quantity of loose Bacon”

for “two Barrels of Rice, and a Hogshead

of Molosses.” (Information of David, 46)

With

temptation – or necessity as Stede

preferred to think of what they did –

having caused him to stray over to the

dark side once again, he realized the need

to protect his pardon. If anyone got wind

of what they were doing, they would once

again be hunted men. So Stede Bonnet

became Captain Thomas and Revenge,

the Royal James. With

temptation – or necessity as Stede

preferred to think of what they did –

having caused him to stray over to the

dark side once again, he realized the need

to protect his pardon. If anyone got wind

of what they were doing, they would once

again be hunted men. So Stede Bonnet

became Captain Thomas and Revenge,

the Royal James.

Captain Manwareing and his crew were among

those who fell victim to Stede and his

men. One evening they anchored “at Cape James

about Nine a-clock at Night.” Pirates,

“well arm’d with Guns, Swords, and

Pistols,” boarded his vessel and promised

that he would come to no harm as long as

he was civil. They asked about his cargo,

which was “Rum, Molosses, Sugar, Cotton,

and Indigo.” Then Captain Manwareing was

required to accompany several pirates

“with two of his Men . . . on board the Royal

James” while four other pirates

remained on his vessel. (Information of

Capt., 49)

Now that he was formally a prisoner,

Manwareing was forced to accompany Stede

to Cape Fear River, a journey of eleven

days. By the time they finished looting

his ship, they had helped themselves to

“twenty six Hogsheads of Rum, three

Teirces, and three Barrels; twenty five

Hogsheads and Teirces of Molosses; three

Teirces and three Barrels of Sugar; two

Pockets of Cotton, and two Bags of Indigo

. . . nineteen Pistoles, two Half-Moidores

of Gold, fourteen Crowns, and a Silver

Watch . . . and one Pair of Silver Buckles

. . . .” (Information of Capt., 49)

Manwareing would remain with the pirates

and during his stay, he later testified,

the pirates “were civil to me, very civil:

But they were all very brisk and merry;

and had all Things plentiful, and were

a-making Punch, and drinking.” (Tryals,

13)

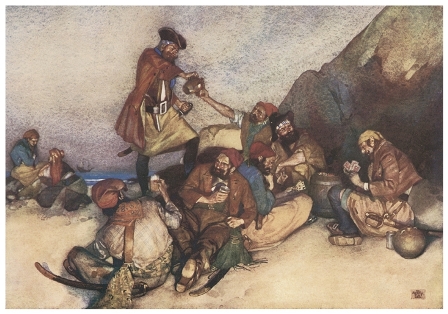

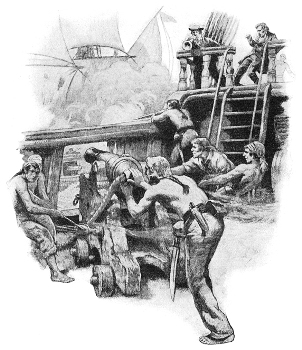

Pirate scene from The Pirates of Penzance

(1911) by William Russell Flint

(Source: Dover's Pirates CD-Rom & Book)

Although the shores of Cape Fear were

sparsely populated, word spread that

pirates were in the area.

[A] Pirate Sloop of ten

Guns and sixty Men was at Cape Fear

River, to the Northward of this Port,

with two Prizes, and had there begun

to careen and refit. (Moss, 102)

The Council

of South Carolina heard the rumors and

took them seriously; they were not in the

mood for a repeat of Thache’s blockade.

One of the leading citizens of Charles

Town and the colony’s receiver general, Colonel William

Rhett, volunteered to hunt down the

pirates. Not wishing to look a gift horse

in the mouth, Governor

Robert Johnson accepted and

immediately issued the necessary paperwork

for Rhett to proceed. Once preparations

were completed, he set sail with two

sloops under his command: the eight-gun Henry

(seventy men) and the eight-gun Sea

Nymph (sixty men). John Master and

Fayrer Hall were the captains of the two

vessels, respectively.5

Rhett was on board Henry. The Council

of South Carolina heard the rumors and

took them seriously; they were not in the

mood for a repeat of Thache’s blockade.

One of the leading citizens of Charles

Town and the colony’s receiver general, Colonel William

Rhett, volunteered to hunt down the

pirates. Not wishing to look a gift horse

in the mouth, Governor

Robert Johnson accepted and

immediately issued the necessary paperwork

for Rhett to proceed. Once preparations

were completed, he set sail with two

sloops under his command: the eight-gun Henry

(seventy men) and the eight-gun Sea

Nymph (sixty men). John Master and

Fayrer Hall were the captains of the two

vessels, respectively.5

Rhett was on board Henry.

Consequences

of Temptation

When Colonel

Rhett’s sloops reached the harbor entrance

in 1718, they stopped at Sullivan’s

Island. There, Rhett encountered a

shipmaster named Cook, who had come north

from Antigua. He had just survived a

pirate attack by the notorious Charles

Vane, and his wasn’t the only vessel

that had been taken. As far as Rhett was

concerned, Vane posed the greater threat

to Charles Town, so he and his men went in

search of Vane. Finding no trace of

these pirates, Rhett resumed his original

plan and, on 26 September, Henry and

Sea Nymph arrived at Cape Fear

River. When Colonel

Rhett’s sloops reached the harbor entrance

in 1718, they stopped at Sullivan’s

Island. There, Rhett encountered a

shipmaster named Cook, who had come north

from Antigua. He had just survived a

pirate attack by the notorious Charles

Vane, and his wasn’t the only vessel

that had been taken. As far as Rhett was

concerned, Vane posed the greater threat

to Charles Town, so he and his men went in

search of Vane. Finding no trace of

these pirates, Rhett resumed his original

plan and, on 26 September, Henry and

Sea Nymph arrived at Cape Fear

River.

Before long, the hunters spied the masts

of what they assumed were the pirate ship

and her prizes. Unfortunately, both Henry

and Sea Nymph ran aground and

it was dark before they got free. During

this time, the pirates had spotted the

newcomers and Stede sent out three canoes

to find out who they were. It didn’t take

long for his scouts to learn the truth and

hie back to the Royal James (Revenge)

with their alarming news.

Stede issued orders to prepare for battle.

Although not everyone was keen to heed

them, he gave them no choice. One pirate

later testified that “Major Bonnet declared,

if any one refused to fight, he would blow

their Brains out.” (Tryals, 19)

Ignatius

Pell, who would testify for the

Crown, concurred. Stede had been about to

deal with a pirate named Thomas Nichols,

but “one that Major Bonnet loved

very well,” had just been slain.

Otherwise, he would have “blowed his

Brains out; for he had his Pistol ready.”

(Tryals, 25)

Death might be

the consequence for his men if they dared

to refuse, but Stede wasn’t about to let

South Carolinians escape without

consequences either. He summoned one of

his prisoners, Captain Manwareing, with

whom he shared a letter that he had

written.

[I]n case the Vessels which

then appeared . . . were sent from South

Carolina to fight

or attack them, and he got clear off,

then he the said Bonnet would send

that Letter to the Governor of South

Carolina.

. . . the

Substance of that Letter . . . did

contain in effect, That he the said Bonnet

would burn and destroy all Vessels

going in or coming out of South

Carolina. (Affidavit, 50)

Of course, the

two hunters were from South Carolina, but

even had he known of the threat, Rhett

wasn’t about to back down.

Stede was

determined to get free and devised a plan.

The next morning, the pirates weighed

anchor and headed for the Atlantic. Stede

intended to pass the intruders with all

guns blazing; his hope was that the

hunters would be so disabled that pursuit

would be impossible. This would then allow

Royal James to have free access to

the ocean and freedom. Rhett, on the other

hand, had other plans. He placed his

sloops so that the Royal James

would have to sail between Henry and

Sea Nymph, opening the pirates up

to broadsides from both directions. Stede was

determined to get free and devised a plan.

The next morning, the pirates weighed

anchor and headed for the Atlantic. Stede

intended to pass the intruders with all

guns blazing; his hope was that the

hunters would be so disabled that pursuit

would be impossible. This would then allow

Royal James to have free access to

the ocean and freedom. Rhett, on the other

hand, had other plans. He placed his

sloops so that the Royal James

would have to sail between Henry and

Sea Nymph, opening the pirates up

to broadsides from both directions.

Of course, no one asked the river what it

had planned. The water was shoaly and

narrow, making it easy for vessels to run

aground. Which was exactly what happened

to all three sloops. Then it became a race

to see which one got free first. In the

meantime, the donnybrook became a

free-for-all.

Henry and Royal James were

close enough to each other to exchange

small arms fire. The former

lay within musqt. shott of

the pirate, and the water falling away

(it being ebb) she keel’d towards him,

which exposed our men very much to

their fire, for near six hours,

dureing wch. time they were engaged

very warmly, untill the water riseing

sett our sloops afloat, about an hour

before the priate . . . (America,

Oct. 21. 730.)

This meant that

Henry leaned toward Royal

James, making it easier for the

pirates to pepper the hunters with lead. Royal

James leaned away from their

pursuers, prohibiting Rhett and his men

from effectively targeting the pirates.

While Sea Nymph was also aground

and in range of Royal James’s guns,

her crew could do little to help Rhett and

his men. This stalemate went on for five

hours, with the Henrys and the Jameses

taunting each other in between pistol

shots.

As the tide came in, Henry floated

free first. The sloop retreated to deeper

water and set about making repairs. As

soon as they were ready, Rhett headed

toward the Royal James. He

expected heavy fighting; instead, the white

flag of surrender had been hoisted.

Although a few pirates objected to

yielding, Rhett took command of the pirate

sloop with little interference. This was

when he found out exactly whom he had

captured. (Remember, Stede had been using

an alias.) Rhett was delighted to hear he

had captured Major Bonnet.

The final tally of casualties? Seven

pirates died; five suffered wounds, some

severe enough that two more soon

succumbed. The Henrys lost ten men and

fourteen were wounded. Sea Nymph’s

losses were relatively few: two killed,

four injured.

Three days after what became known as the

Battle of Cape Fear River or the Battle of

the Sandbars, the five sloops – Rhett’s

two, the pirates’, and the two freed

pirate prizes – departed the river on the

last day of September 1718. They arrived

in Charles Town on 3 October “to the great

Joy of the whole Province.” (Prefatory, v)

Two days passed before any of the pirates

were offloaded. One reason for the delay

might have been because Charles Town

lacked a gaol. Instead, Provost Marshal

Nathaniel Partridge oversaw the transfer

of thirty pirates to the Watch

House, “constructed around 1701 at

the intersection of Broad and East Bay

Streets.” (Butler) According to the

legislators, it was to be “a brick watch

house, capable of containing thirty men.”

(Butler) The building’s interior

must have included some

sort of interior partition that

separated the watchmen and their arms

and accoutrements from their

prisoners. The partition probably

consisted of a masonry wall, or

several partial walls, that

incorporated some arrangement of iron

bars to create a cage-like enclosure

within the larger interior space. . .

. Considering that it was intended to

hold a relatively small number of

people for a matter of hours, however

. . . it probably occupied a

relatively small portion of the

building’s footprint. (Butler)

The only pirate

who did not have to suffer the rank smell

and crowded confines of the Watch House

was Stede. He stayed in Partridge’s house.

Once David Herriot and Ignatius Pell

agreed to turn king’s evidence, they were

taken from the Watch House and confined

with Stede. Two sentries stood guard

outside to make certain the prisoners

stayed within.

How closely the sentries watched became a

matter of debate. On 24 October, Stede

donned women’s attire and escaped with

Herriot. With the help of three slaves

belonging to Richard

Tookerman, a local resident, the

escapees fled in a canoe. It wasn’t long

before people spoke of collusion and

bribery whenever they discussed the

escape. Attorney General Richard Allein

would even make mention of these at the

upcoming trials.

I am sensible, Bonnet

has had some Assistance in making his

Escape; and if we can discover the

Offenders, we shall not fail to bring

them to exemplary Punishment. (Tryals,

9)

“Hue and

Crys and Expresses by Land

and by Water” were sent out,

but there was no word of the escapees even

though Governor

Johnson offered a bounty of £700 for

Stede’s return. (Tryals, 9) So, the

governor called for Colonel Rhett, who set

forth once again to recapture Stede.

Shortly after the pirates were

incarcerated, the legislature passed “An

Act for the more speedy and regular Trial

of Pirates.” This statute allowed South

Carolina to appoint “the judge or judges

of the Admiralty or Vice-Admiralty . . .

[who] shall have full power to do all

things in and about the inquiry, hearing,

determining, adjusting and punishing,” as

well as to try the accused and impanel

“twelve good and lawful men, inhabitants

of this Province” to sit in judgement of

the defendants. (Cooper, 42)

Backed by this new law, the trials of the

pirates could begin. They would be tried

in batches because the vice-admiralty

court was held in the home of Garret

Vanvelsen, a prominent shoemaker in the

city. Nicholas

Trott presided over all the trials.

He was the nephew of Sir Nicholas Trott,

who had governed the Bahama Islands in the

late 1600s and made the mistake of

accepting a bribe from Henry

Every, one of the most infamous

pirates of his day. South Carolina’s chief

justice would not repeat his uncle’s

mistake. As far as he was concerned,

pirates were hostis humani generis

(enemy of mankind). While he oversaw the

trials, his brother-in-law, William Rhett,

was out hunting the escapees.

Helping Trott

were ten assistant judges. Six were

attorneys: George Logan, Alexander Parris,

Philip Dawes, George Chicken, Benjamin de

la Conseillere, and Samuel Dean. Two

gentlemen (Edward Brailsford and John

Croft) also served as did two captains,

Arthur Loan and John Watkinson. The

pirates would be tried by Richard Allein,

South Carolina’s attorney general, and

Thomas Hepworth, assistant prosecutor.

This was a period in judicial history when

the thinking of the court was that an

innocent defendant “‘ought to be able to

demonstrate it for the jury by the quality

and character of his reply to the

prosecutor’s evidence.’” (British,

2:xii) Therefore, the pirates had no need

for “defence lawyers to object to or probe

the state’s case.” (British, 2:vii)

Equally true in this time was that juries

weren’t necessarily impartial and they

were rarely on the same footing socially

and financially as the pirates. They often

owned property – pirates didn’t legally –

and they were upstanding citizens – by

definition, piracy was a crime. The men

who sat on the upcoming trials “were court

‘insiders’ who heard several cases each

session and enjoyed a working relationship

with the judge that expedited the business

of justice but often led them too easily

to endorse the inequities of the legal

system.” (British, 2:xiii) For

these trials there were essentially “two

juries (with minor variations in

membership) . . . the first jury sat on

the first, third, fifth, sixth, eighth and

tenth trials; the second jury on the

second, fourth, seventh and ninth.” (British,

2:323) Thus, “impartial” wasn’t

necessarily a descriptor of those who

served in judgement on the thirty-four

pirates, including Stede, indicted for two

piracies: the Francis under the

command of Peter Manwareing, and the Fortune,

whose master was Thomas Read. Except for

James Wilson (Dublin, Ireland) and John

Levit (North Carolina), thirty pled not

guilty to these charges. Daniel Perry of

Guernsey pled guilty to one indictment and

not guilty to the other.

Continue

reading

Notes:

1. Between

1689 and 1740, an able-bodied seaman

(AS) earned 25 to 55 shillings per month

or £15 to £33 a year. (Ordinary seamen

and those rated lower earned less,

whereas officers earned more in the

merchant marine.) That £15 in 1717 (when

Bonnet sailed) equates to UK £2,603.52

or US $3,281.44 in February 2024. The

higher amount equates to UK £5,727.74 or

US $7,219.17 today. (This information

comes from Peter T. Leeson’s The

Invisible Hook (Princeton, 2009),

the Bank

of England’s Inflation Calculator,

and Xe.com.)

2. Sixty-six of La

Concorde's crew and 455 slaves were released

on Bequia Island. Several barrels of beans were

given them for food. Perhaps enjoying the irony,

Thache gave Captain Pierre Dosset a previously

captured sloop named Mauvaise Rencontre,

which in English meant "Bad Encounter."

3. The hanging of six pirates

to which Thache refers pertains to the trial of

the survivors following the demise of Samuel

Bellamy's Whydah. Two of the eight

defendants were acquitted, but six danced the

hempen jig.

4. The Triple Alliance was

formed in January 1717 as a means of protection

against Spain, which wanted to change the peace

treaty that ended the War of the Spanish

Succession four years earlier. In August of 1717,

Austria would join the alliance and the war became

known as the War of the Quadruple Alliance. It

lasted into 1720.

5. At this time, Captain Hall

had been a ship’s master for a minimum of four

years and he had worked on ships significantly

longer than that. The interesting fact is that he

was connected to Richard Tookerman, who may have

already had dealings with Stede or soon would.

Barker points out in his article that while no

documentary evidence exists as to any orders

given, the perception exists that he didn’t want

Stede to be captured, which is why Captain Hall

did not participate as fully as he might have

during the battle between Rhett’s forces and the

pirates.

Colonel Rhett certainly believed this. Two years

later, he would tell high-placed citizens of

Charles Town that he could prove that Hall was a

pirate. Hall sued, saying the claims were

slanderous. Although he won his case because Rhett

never appeared in court, he received no damages.

Resources:

“The

Affidavit of Capt. Peter Manwareing” in The

Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet. Printed for

Benj. Cowse, M. DCC.XIX., 50.

“America

and West Indies: January 1718, 1-13” in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. His

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1930. (Jan.

6. 298.)

“America

and West Indies: May 1718” in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. His

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1930. (May

31. Bermuda. 551)

“America

and West Indies: June 1718” in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. His

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1930. (June

18. Charles Towne, South Carolina. 556.)

“America

and West Indies: October 1718,” in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. His

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1930. (Oct.

21. Charles town, South Carolina. 730.)

Baker, Daniel R. “Stede Bonnet: The Phantom

Alliance,” The Pyrate’s Way (Summer

2007), 21-25.

Bialuschewski, Arne. “Blackbeard

off Philadelphia: Documents Pertaining to the

Campaign against the Pirates in 1717 and 1718,”

The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and

Biography v.134: no. 2 (April 2010),

165-178.

“Boston,” The Boston News-Letter 16 June

1718 (739), 2.

British Piracy in the Golden Age: History and

Interpretation, 1660-1730 edited by Joel

H. Baer (volume 2). Pickering & Chatto,

2007.

Brooks, Baylus C. Quest for Blackbeard: The

True Story of Edward Thache and His World.

Independently published, 2016.

Butler, Nic. “The

Watch House: South Carolina’s First Police

Station, 1701-1725,” Charleston Time

Machine (3 August 2018).

Cooper, Thomas. “An Act

for the More Speedy and Regular Trial of

Pirates. No. 390.” in The Statutes at

Large of South Carolina. Printed by A. S.

Johnston, 1838, 3:41-43.

Cordingly, David. Under the Black Flag: The

Romance and the Reality of Life Among the

Pirates. Random House, 1995.

Dolin, Eric Jay. Black Flags, Blue Waters:

The Epic History of America’s Most Notorious

Pirates. Liveright, 2018.

Downey, Christopher Byrd. Stede Bonnet:

Charleston’s Gentleman Pirate. The History

Press, 2012.

Fictum, David. “'The

Strongest Man Carries the Day,' Life in New

Providence, 1716-1717,” Colonies, Ships,

and Pirates (26 July 2015).

Hahn, Steven C. “The

Atlantic Odyssey of Richard Tookerman:

Gentleman of South Carolina, Pirate of

Jamaica, and Litigant before the King’s Bench,”

Early American Studies 15:3 (Summer 2017),

539-590.

History

of South Carolina edited by Yates Snowden.

Lewis Publishing, 1920, 1:173-182.

“The Information of Capt. Peter Manwareing” in The

Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet. Printed for

Benj. Cowse, M. DCC. XIX., 49.

“The Information of David Herriot and Ignatius

Pell” in The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet.

Printed for Benj. Cowse, M. DCC. XIX., 44-48.

Johnson, Charles. A

General History of the Pyrates. T. Warner,

1724.

Logan, James. “James

Logan letter to Robert Hunter, October 24,

1777." Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Discover.

(Special

note, the date of the entry is misleading as the

date of the letter [viewable and downloadable here]

is 24 8 1717 or 24 August 1717. James Logan was

deceased in 1777.)

The London

Gazette. Issue

5573 (14 September 1717), 1.

Marley, David F. “Thatch, Edward, Alias

‘Blackbeard’ (fl. 1717-1718),” Pirates of

the Americas. ABC-CLIO, 2010, 2:787-799.

Malesic, Tony. E-mail posting on PIRATES about

Richard Tookerman, 26 September 2001.

Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the

Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet.

Köehler, 2020.

Moss, Jeremy. “Stede

Bonnet, Gentleman Pirate: How a Mid-life

Crisis Created the ‘Worst Pirate of All Time,’”

History Extra (4 January 2023).

“Philadelphia, October 24th,” The Boston

News-Letter 11 November 1717 (708), 2.

“A Prefatory Account of the Taking of Major

Stede Bonnet, and the other Pirates, by the two

Sloops under the Command of Col. William Rhett”

in The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet.

Printed for Benj. Cowse, M. DCC. XIX., iii-vi.

Ramsay, David. Ramsay’s

History of South Carolina: From Its First

Settlement in 1670 to the Year 1808. W. J.

Duffie, 1858.

“Top-Earning

Pirates,” Forbes (19 September 2008).

The

Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other

Pirates. Printed for Benjamin Cowse,

MDCCXIX.

Woodard, Colin. The Republic of Pirates:

Being the True and Surprising Story of the

Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them

Down. Harcourt, 2007.

Copyright ©2024 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |