Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

In Memoriam

Verboten!

by Cindy Vallar

Look

at any of the surviving articles of agreement under

which pirates sail, and you’ll notice that some are

warnings to the crew. Harmony amongst themselves,

otherwise discord erupts and chaos reigns. This is

why some crews forbid women on their ships. Look

at any of the surviving articles of agreement under

which pirates sail, and you’ll notice that some are

warnings to the crew. Harmony amongst themselves,

otherwise discord erupts and chaos reigns. This is

why some crews forbid women on their ships.

No Boy or

Woman to be allowed amongst them. If any Man

were found seducing any of the latter Sex, and

carried her to Sea, disguised, he was to suffer

Death. (Johnson, 171)

When ships were captured

and women were found aboard, as happened when

Bartholomew Roberts’s men took Onslow, “they

put a Centinel immediately over her to prevent ill

Consequences from so dangerous an Instrument of

Division and Quarrel.” (Johnson, 171) Note: This

wasn’t done to protect the lady; rather, it was done

to keep the men from arguing or fighting amongst

themselves. Nor did this mean the lady was safe from

molestation. “[T]hey contend who shall be Centinel,

which happens generally to one of the greatest

Bullies, who, to secure the Lady’s Virtue, will let

none lye with her but himself.” (Johnson, 171)

This practice came back to haunt William Mead and

David Simpson. According to her testimony, Elizabeth

Trengove swore Mead

was very

rude to her, swearing and cursing, as also

forcing her hoop’d Petticoat off; and to prevent

more of his Impudence, which she was afraid off,

went down into the Gunner’s Room by Advice of

one Mitchel a Pyrate. (Full,

34)

She did as Mitchel bid,

but other pirates witnessed her passage through the

ship. Their threats brought Roberts to the scene and

he ordered her locked up until he had time to decide

her outcome. The guard he assigned to protect her,

Quartermaster David Simpson, assaulted her. At his

trial, he denied none of the facts and was judged

guilty. He was hanged on 3 April 1722, “without the

Gates of the Castle . . . [his] Body hung in

Chains.” (Full, 24) Simpson supposedly walked

to the

Gallows without a Tear . . . at seeing a Woman

that he knew, said, ‘he had lain with that B—h

three times, and now she was come to see him

hanged.’ (Johnson, 258)

The court decided the

king should decide the outcome of Mead’s fate, so he

was sent back to Marshalsea, a prison in

England. Mitchel might have been John Mitchell, who

was judged guilty and condemned to serve seven years

of hard labor, which essentially was a death

sentence in Africa.

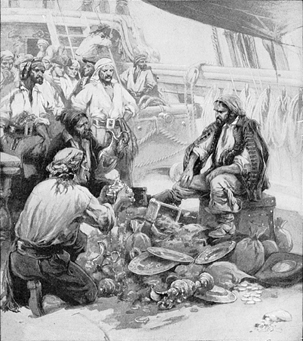

Pirates of the nineteenth century

tended to be more brutal than their earlier

counterparts. Their catchphrase seemed to be “Dead

men tell no tales.” And their idea of “fun” was

certainly not how the victims defined that word. In

1828, Benito de Soto gave orders to

sink Morning Star, but not before his men

plundered the ship and the women aboard. When the

pirates boarded, Annie Logie, one of the military

wives bound for home, locked herself and the other

women and their children in the roundhouse, but

later admitted, Pirates of the nineteenth century

tended to be more brutal than their earlier

counterparts. Their catchphrase seemed to be “Dead

men tell no tales.” And their idea of “fun” was

certainly not how the victims defined that word. In

1828, Benito de Soto gave orders to

sink Morning Star, but not before his men

plundered the ship and the women aboard. When the

pirates boarded, Annie Logie, one of the military

wives bound for home, locked herself and the other

women and their children in the roundhouse, but

later admitted,

We had no

means to defend ourselves barricaded in there,

all the while hearing shouts in foreign tongues.

Later our menfolk were forced below into the

cargo hold by the attackers and the hatch covers

were hammered shut. (Ford, 70)

She warned the women not

to resist, and when the leader demanded that she be

brought to him, she went.

Passing

her infant to one of the women, she slid open

the iron door lock and was half-dragged onto the

sunlit quarterdeck . . . [and] was shoved

roughly towards the makeshift canopy of torn

sailcloth draped over a spar where Barbazan sat.

(Ford, 72-73)

As far as the pirates

were concerned, it was time to celebrate. The ship’s

cook cooked “four fowl from the hen cook” and

stemware was taken from the captain’s cabin to drink

from. While the pirates imbibed, Anne prayed that

they would become so intoxicated that they would

pass out. It was not to be.

As dusk

fell, reeking of sweat and wine, Barbazan leered

at Anne Logie, shoving a wine bottle at her,

fondling her with a greasy hand, and when her

husband lunged towards Barbazan, he was

overpowered by two of the pirates who dragged

him towards the cargo hatch. (Ford, 74)

Women suffer at hands of

pirates aboard Morning Star

(Source: The Pirates Own Book

by Charles Ellms, 1837)

Anne and the others suffered until the drink finally

knocked the pirates senseless. It was a short

reprieve, because the next morning Captain Benito de

Soto, who was still aboard the pirate ship, ordered

his men to lock up all the captives and drill holes

in Morning Star’s hull. Instead of waiting

to make certain she sank, the pirates sailed away.

The women managed to escape from the roundhouse and

free their husbands and the crew. Together, they

manned the pump and kept the ship afloat long enough

for a passing vessel to rescue them several days

later.

As despicable as such encounters were, pirates were

more likely to follow the adage of all’s fair in

love and war, and pirates of the golden age and

later made it clear that they were the enemies of

all mankind . . . at sea. It was often a different

story when they were on land.

While women, for the most part, were excluded from

pirate ships per the companies’ articles, they were

a welcome sight when pirates went ashore with money

to burn. The 1680 census of Port Royal, Jamaica,

mentioned only a single brothel among the many

structures in the city. The proprietor was John

Starr, and his workers included twenty-three women

and two Blacks. There must have been other such

establishments, but they were either significantly

smaller or within buildings where selling ale or

punch was the primary business.

For law-abiding people, Port Royal was so bad that it

was likened to the biblical city of Sodom because of the

proliferation of taverns, ordinaries, and brothels.

The latter included

‘such a

crew of vile strumpets, and common prostitutes,

that tis almost impossible to civilize’ the

town, since they were ‘its walking plague,

against which neither cage, whip nor

ducking-stool would prevail.’ (Preston, 28)

These women weren’t

necessarily raving beauties.

In their

smockes ore linen peticotes, bare-footed without

shoes or stockins, with a straw hatt and a red

tobacco pipe in their mouths, [they would]

trampouse about their streets in this their

warlike posture, and thus arrayed will booze a

cupp of punch cumly with anyone. (Pawson,

144)

Some pirates ventured

into Betty Ware’s tavern where, once inebriated,

they would cross cutlasses in front of women who

spoke and behaved more like men. They had names like

Buttock-de-Clink Jenny, No-Conscience Nan, and

Salt-Beef Peg. One of the most famous was Mary Carleton, also known as

the German Princess because she assumed such a role

after a case of mistaken identity.

Decking

herself in jewels and finery and passing as

Maria de Wolway, she came to London as a noble

German lady forced to flee an unwanted marriage.

Her appearance of wealth was aided by false

letters from the continent attesting to estates.

(Todd)

She married a man named

Carleton in 1663, who hoped to gain those

properties. When he didn’t and Mary’s true identity

became known, she was arrested and tried on charges

of bigamy. She never swayed from her story during

the trial; she even turned the tables on Carleton,

saying he was the one spreading lies. She was

acquitted, had several lovers, and changed her

identity several more times. Later, she filched a

silver tankard and got caught. A jury sentenced her

to hang; instead, she was transported to Port Royal

in 1671. (Transport became more common two decades

later because so many strumpets were crowding gaols.

It cost the Crown £8 per person to send them

overseas.)

She left an impression on those who frequented Port

Royal. A contemporary said:

A stout

frigate she was or else she never could have

endured so many batteries and assaults . . . she

was as common as a barber’s chair: no sooner was

one out, but another was in. (Preston, 28)

Even after Mary returned

to London, she continued her deceits and thievery,

which again landed her in jail. This time around,

she didn’t escape the hangman’s noose on 22 January

1673.

The most powerful pirate in Asian waters was once a

prostitute. She was visited by the pirate Zheng Yi,

who commanded the Red Flag Fleet. He asked her to be

his wife, but she agreed to do so only if she

received an equal portion of plunder and if he

treated her as his equal. Zheng Yi Sao would later

become powerful enough to threaten the existence of

the imperial navy, and her influence and success

eventually allowed her to dictate the terms of her

retirement with the Chinese emperor.

Whereas Western pirates frequented brothels on land,

many brothels in China were found on the water. Karl

Gützlaff, a nineteenth-century German missionary,

wrote,

As soon as

we had anchored, numerous boats surrounded us,

with females on board, some of them brought by

their parents, husbands, or brothers. I

addressed the sailors who remained in the junk,

and hoped that I had prevailed on them, in some

degree, to curb their evil passions. But, alas!

no sooner had I left the deck, than they threw

off all restraint; and the disgusting scene

which ensued, might well have entitled our

vessel to the name of Sodom. (Gutzlaff, 88)

The floating brothels in

Canton were known as “flower boats,” and in 1770,

estimates placed the number of such establishments

at 8,000.

Some historians have suggested that some pirates

preferred to rendezvous with other men. Among

Western pirates, David Cordingly wrote, “it seems

likely that the percentage of pirates who were

actively homosexual was similar to that in the Royal

Navy, and reflected the proportion of homosexuals in

the population at large.” (163) Benerson Little has

“come across little to support” the opinion that

pirates “were actually active homosexual

communities.” His research suggests the opposite.

(Little, Sea, 209)

In Asia, however, the lines among personal

relationships between pirates and their mates or

pirates and captives was more blurred. Having more

than one partner wasn’t unusual. When Zhang Bao was

a young boy, he was taken captive by Zheng Yi. The

pirate chief took Zhang Bao under his wing, teaching

him to be a pirate and bonding with him personally

to keep him loyal. After Zheng Yi’s death, Zhang Bao

became Zheng Yi Sao’s lover; she had been his

adoptive mother since she was married to Zheng Yi.

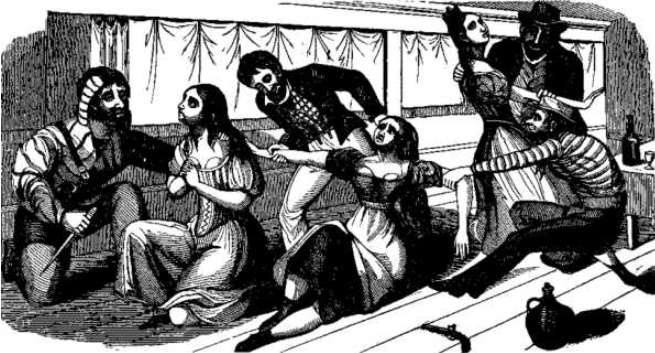

Pirates capture John Turner by

unknown artist, circa 1807

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

J. L. Turner, an Englishman

serving as first mate of a trading ship, found

himself the prisoner of Cheng Yat in 1806. He

observed the Red Flag Fleet’s treatment of women.

With

respect to the women who fall into their hands,

the handsomest are reserved by them for wives

and concubines; the chiefs and captains having

frequently three or more, the others seldom more

than one; and having once made the choice of a

wife, they are obliged to be constant to her, no

promiscuous intercourse being allowed amongst

them. (Turner, 13)

A contemporary of Zheng Zhilong mentions that

“As a young man, [he] was pleasing to the eye, and

Li Dan took him as his male lover.” (Andrade, 25)

Whether this was true or not cannot be determined

because the biographer was relatively unknown and no

documentary evidence exists to prove or disprove the

statement. At the time, though, homosexuality was a

common practice among seventeenth-century seafarers

in the Fujian region of China. That said, Zheng

Zhilong did have two wives, one Chinese and one

Japanese.

Illicit trysts weren’t the only forbidden items that

pirates enjoyed. Some were dangerous to the pirates’

health. Opium’s addictiveness

eventually led to war between Imperial China and

Great Britain. Asian pirates often chewed betel nuts to pass the time.

Chewers were easy to spot because the pirates’

smiles would be deep red or purple. The pirates who

captured Edward Brown, a seaman taken

captive in the 1850s, tried to share the betel-net,

which they called “eu-kow-ong,” with him.

When I

declined it, they appeared quite surprised, and

would not be satisfied that I did not use it;

but asked to look at my teeth, and showed

symptoms of disgust at their natural white

colour, at the same time pointing to their own,

which were as black as ebony. They chew this

nauseous nut all day long, and only take it out

of their mouths while they are eating. . . .

Black teeth are

with them an embellishment, rather than a

disfigurement; they are coveted as much by them,

as a good head of hair is by the English; and

they are a necessary adjunct to opulence and

respectability. (Brown, 117-118)

In modern times, Somali

pirates prefer khat, a stimulant that can be

chewed or brewed as tea. Chewing is the preferable

way to partake of this “flower of paradise,” and the

pirates will chew it for hours while with their

friends. The bitter taste often compels them to

drink highly sweetened tea or 7UP. When experiencing

the euphoria that khat produces, pirates tend to

think they are invincible. According to Abdirizak

Ahmed, “I would either become relaxed and talkative,

or a sex-crazy maniac bent on immediate satiation.”

(Bahadur, 93)

Montage of Somali pirates that

captured MV Faina

by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd

Class Jason R. Zalasky, 2008

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Smoking was another habit among Asian pirates, and

Edward Brown did join them.

[T]hey

offered me paper cigars, which I gladly

accepted; but when they gave me the materials,

they were surprised that I could not roll them

as neatly as they did themselves. (Brown,

118)

Western pirates also

liked to smoke, although their preference was pipe smoking. Among the

artifacts recovered from Queen Anne’s Revenge

were pipes of white clay. After getting caught with

Stede Bonnet, David Herriot

said that they “took two Ships bound from Virginia

for Glascow . . . and took about one hundred Weight

of Tobacco out of each . . . .” (Tryals of Major,

46) It was plunder frequently taken that was easily

and immediately divided amongst the pirates for

their enjoyment. Smoking was so common that John Philips made mention of

it in his company’s articles.

That Man shall snap his Arms, or

smoak Tobacco in the Hold, without a cap to his

Pipe, or carry a Candle lighted without a

Lanthorn, shall suffer the same Punishment as in

the former Article. (In, 222 n255) That Man shall snap his Arms, or

smoak Tobacco in the Hold, without a cap to his

Pipe, or carry a Candle lighted without a

Lanthorn, shall suffer the same Punishment as in

the former Article. (In, 222 n255)

The aforesaid punishment

was “Moses’ Law (that is 40 stripes lacking one) on

the bare Back.” (In, 222, n255)

Phillips was one of those who used tobacco on his

ship. Among the articles taken from him after his

capture, was “a curious tobacco box.” (Pirates, 233)

Tobacco was such a fixture in pirates’ lives that

they even smoked it when trying would-be deserters

who sailed with Bartholomew Roberts.

The Place

appointed for their Tryals, was the Steerage of

the Ship; in order to which, a large Bowl of Rum

Punch was made, and placed upon the Table, the

Pipes and Tobacco being ready, the judicial

Proceedings began; the Prisoners were brought

forth, and Articles of Indictment against them

read; they were arraigned upon a Statute of

their own making, and the Letter of the Law

being strong against them, and the Fact plainly

proved, they were about to pronounce Sentence,

when one of the Judges mov’d, that they should

first Smoak t’other Pipe; which was accordingly

done.

The pause permitted one

pirate to stand up in defense of one of the

defendants. After some more smoking and further

deliberation, the other judges concurred that Henry

Glasby would escape punishment. As to the remaining

defendants, the pirates were adamant that they must

be punished, but they were permitted to choose their

own executioners before being “ty’d immediately to

the Mast, and there shot dead . . . .” (Johnson,

185-187)

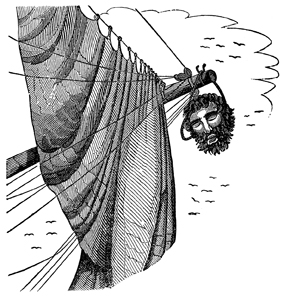

Roberts’s motto of “a merry Life and

a short one” proved merry for those standing in

judgment and a short one for those brought before

the bar. Of course, pirates weren’t the only ones

who liked to celebrate, especially if the merriment

showed exactly what victims of piracy thought about

the perpetrators of their misfortune. Roberts also

suffered a short life, being shot in the throat

after plundering the seas for only three years.

Blackbeard’s comeuppance came after about a year and

a half of terrorizing victims. He died during an

engagement with Lieutenant Robert Maynard and his

men in November 1718. Thache’s head was then severed

from his body and hung from the bowsprit of

Maynard’s sloop. Roberts’s motto of “a merry Life and

a short one” proved merry for those standing in

judgment and a short one for those brought before

the bar. Of course, pirates weren’t the only ones

who liked to celebrate, especially if the merriment

showed exactly what victims of piracy thought about

the perpetrators of their misfortune. Roberts also

suffered a short life, being shot in the throat

after plundering the seas for only three years.

Blackbeard’s comeuppance came after about a year and

a half of terrorizing victims. He died during an

engagement with Lieutenant Robert Maynard and his

men in November 1718. Thache’s head was then severed

from his body and hung from the bowsprit of

Maynard’s sloop.

When the

vessel which captured Blackbeard returned to

Virginia, they set up his head on a pike planted

at “Blackbeard point,” then an island.

Afterwards, when his head was taken down, his

skull was made into the bottom part of a very

large punch bowl, called the infant, which was

long used as a drinking vessel at the Raleigh

tavern at Williamsburg. It was enlarged with

silver, or silver plated; and I have seen those

whose forefathers have spoken of drinking punch

from it, with a silver ladle appurtenant to that

bowl. (Watson, 2: 221)

Fact or fiction, who’s to

say? Does it matter? It makes for a great story, and

at the time, more than a few colonists were happy to

celebrate the demise of the most notorious pirate of

the day.

Resources:

“America

and West Indies: March 1678,’ in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 10,1677-1680 edited by W.

Noel Sainsbury and J. W. Fortescue. London, 1896,

220-231 (March-Sept. St. Christopher’s. 645.)

“America

and West Indies: August 1698, 22-25,’ in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 16,1697-1698 edited by J. W.

Fortescue. London, 1905, 399-406 (Aug. 25. 771.).

“America

and West Indies: June 1718,” in Calendar of

State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies:

Volume 30, 1717-1718 edited by Cecil Headlam.

London, 1930, 264-287. (June 18. Charles Towne,

South Carolina. 556.).

Andrade, Tonio.

Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China’s First

Great Victory Over the West. Princeton,

2011.

Antony, Robert J. Like

Froth Floating on the Sea: The World of Pirates

and Seafarers in Late Imperial China.

Institute of East Asian Studies, University of

California Berkley, 2003.

Appleby, John C. Women

and English Piracy 1540-1720: Partners and

Victims of Crime. Boydell, 2013.

Ashmead, Henry Graham.

History

of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. L.

H. Everts & Co., 1884.

Bahadur, Jay. The Pirates of Somalia: Inside

Their Hidden World. Pantheon Books, 2011.

Bialuschewski, Arne. Raiders

and Natives: Cross-cultural Relations in the Age

of Buccaneers. University of Georgia, 2022.

Bold in Her

Breeches: Women Prostitutes Across the Ages

edited by Jo Stanley. Pandora, 1996.

Borvo, Alain. “Discover

Aluette, the Game of the Cow,” Traditional

Tarot (21 July 2021).

Bradley, Peter T. Pirates

on the Coasts of Peru 1598-1701.

Independently published, 2008.

Brooks, Baylus C. Quest

for Blackbeard: The True Story of Edward Thache

and His World. Independently published,

2016.

Brown, Edward. A

Seaman’s Narrative of the Adventures During a

Captivity Among Chinese Pirates, on the Coast

of Cochin-China. Charles Westerton,

1861.

Burg, B. R. “The

Buccaneer Community” in Bandits at Sea: A

Pirates Reader edited by C. R. Pennell. New

York University, 2001, 211-243.

Choundas, George. The Pirate Primer: Mastering

the Language of Swashbucklers and Rogues.

Writer’s Digest, 2007.

Codfield, Rod. “Tavern

Tales: 1708 Letter,” Historic London

Town & Gardens (2 April 2020).

Cotton, Charles. The

Compleat Gamester. London: Charles Brome,

1710.

Craze, Sarah, and Richard Pennell. “The Truth Behind a Pirate Legend,”

Pursuit (23 March 2021).

Croce, Pat. The

Pirate Handbook. Chronicle Books, 2011.

Dampier, William. A New

Voyage Round the World vol. 1. London:

James Knapton, 1699.

Defoe, Daniel. A

General History of the Pyrates edited by

Manuel Schonhorn. Dover, 1999.

Duffus, Kevin P. The

Last Days of Black Beard the Pirate. Looking

Glass Productions, 2008.

Eastman, Tamara J., and Constance Bond. The

Pirate Trial of Anne Bonny and Mary Read.

Fern Canyon Press, 2000.

Ellms, Charles. The

Pirates Own Book. 1837.

Esquemeling, John. The Buccaneers of America.

Rio Grande Press, 1684.

Exquemelin, Alexander

O. The Buccaneers of America translated by

Alexis Brown. Dover, 1969.

“FAQs:

Beverages,” Food Timeline edited by

Lynne Olver (30 November 2021).

Ford, Michael. “The

Attack of the ‘Last Great Pirate’ – Benito De

Soto, Wellington’s Treasure and the Raid of the

‘Morning Star,’ Military History Now

(21 June 2020).

Ford, Michael E. A. Hunting

the Last Great Pirate: Benito de Soto and the

Rape of the Morning Star. Pen & Sword,

2020.

A Full

and Exact Account of the Tryal of the Pyrates

Lately Taken by Captain Ogle. London:

J. Roberts, 1723.

Fox, Edward Theophilus. “’Piratical Schemes and

Contracts’: Pirate Articles and their Society,

1660-1730.” PhD thesis, University of

Exeter, 2013.

Further

State of the Ladrones on the Coast of China.

Lane, Darling, and Co., 1812.

Geanacopulos, Daphne Palmer. The Pirate Next

Door: The Untold Story of Eighteenth Century

Pirates’ Wives, Families and Communities.

Carolina Academic, 2017.

Gosse, Philip. The Pirates’ Who’s Who. Rio

Grande Press, 1924.

Gutzlaff,

Charles. Three

Voyages Along the Coast of China in 1831,

1832, & 1833. Frederick, Westley

and A. H. Davis, 1834.

Hacke, William. Collection

of Original Voyages. London: James

Knapton, 1699.

Hailwood, Mark. “‘Come

hear this ditty’: Seventeenth-century

Drinking Songs and the Challenges of Hearing the

Past,” The Appendix (10 July 2013).

Hardy, Thomas. “Drinking

Song,” Poetry Nook.

Hartsmar, Markus. “Oscar

Wilde, 1854-1900,” Absinthe.se.

Hughes, Ben. Apocalypse

1692: Empire, Slavery, and the Great Port Royal

Earthquake. Westholme, 2017.

Jacob, Robert. “Popular

Games from the Golden Age!” Robert Jacob.

Jamaica Rose. “Games

Pirates Played,” Pirates Magazine (Summer

2006), 53-55.

Jamaica Rose. “Pirate

Pastimes & Pleasures,” Pirates Magazine

(Summer 2006), 49-51.

Jameson, John Franklin.

Privateering

and Piracy in the Colonial Period:

Illustrative Documents. Macmillan, 1923.

Johnson, Charles. A General

History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most

Notorious Pyrates. London: C. Rivington,

1724.

Kehoe, M. “Booze,

Sailors, Pirates and Health in the Golden Age of

Piracy,” The Pirate Surgeon’s Journals:

Tools and Procedures.

Kehoe, M. “Christmas

Holidays at Sea in the Golden Age of Piracy,”

The Pirate Surgeon’s Journals: Tools and

Procedures.

Kehoe, Mark C. “Fresh

Water at Sea in the Golden Age of Piracy,” The

Pirate Surgeon’s Journals.

Kehoe, M. “Tobacco

and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy,”

The Pirate Surgeon’s Journals: Tools and

Procedures.

Kelleher, Connie. The

Alliance of Pirates: Ireland and Atlantic Piracy

in the Early Seventeenth Century. Cork

University, 2020.

King

James Bible Online.

Labat, Jean-Baptiste. The

Memoirs of Père Labat, 1693-1705

translated and abridged by John Eaden.

Routledge, 2013.

Lane, Kris E. Pillaging the Empire:

Piracy in the Americas, 1500-1750. M. E.

Sharpe, 1998.

Lee, Robert E. Blackbeard

the Pirate: A Reappraisal of His Life and Times.

John F. Blair, 2002.

“Liar’s

Dice,” Awesome Dice.

Little, Benerson. The

Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish

Main, 1674-1688. Potomac Books, 2007.

Little, Benerson. “Of

Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar

Smoking Women,” Swordplay &

Swashbucklers (1 January 2017).

Little, Benerson. The

Sea Rover’s Practice: Pirate Tactics and

Techniques, 1630-1730. Potomac Books, 2005.

Marley, David F. Pirates of the Americas

Volume 1 1650-1685. ABC Clio, 2010.

Marley, David F. Pirates

of the Americas Volume 2 1686-1725. ABC

Clio, 2010.

Mather, Increase. Wo to

Drunkards (second edition). Boston:

Timothy Green, 1712.

McAlister, Zac. “What Is

Black Strap Rum,” Booze Bureau.

Neumman, Charles Fried. History

of the Pirates Who Infested the China Sea,

from 1807 to 1810. Oriental

Translation Fund, 1831.

Parlett, David. “Historic

Card Games,” Games & Gamebooks.

2022.

Pawson, Michael, and

David Buisseret. Port Royal, Jamaica.

University of the West Indies, 2000.

“Pirate

Potheads? On Drugs and Tobacco in the Golden Age

of Piracy,” Gold and Gunpowder (8

December 2023).

The Pirate’s

Pocket-Book edited by Stuart Roberston.

Conway, 2008.

Pirates in Their Own

Words: Eye-witness Accounts of the ‘Golden Age’

of Piracy, 1690-1728 edited by E. T. Fox.

Fox Historical, 2014.

“The Plank

House,” The Marcus Hook Preservation

Society.

Preston, Diana and

Michael. A Pirate of Exquisite Mind: Explorer,

Naturalist, and Buccaneer: The Life of William

Dampier. Walker & Co., 2004.

Pruitt, Sarah. “How

Christmas Was Celebrated in the 13 Colonies,”

History (5 October 2023).

Rogers, Woodes. A

Cruising Voyage Round the World.

Cassell and Company, 1928.

Sanders, Richard. If a Pirate I must be . . .

: The True Story of “Black Bart,” King of the

Caribbean Pirates. Skyhorse, 2007.

Sanna, Antonio.

“Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum”: Representations of

Drunkenness in Literary and Cinematic Narratives

on Pirates,” Pirates in History and Popular

Culture edited by Antonio Sanna. McFarland,

2018, 120-131.

Schenawolf, Harry. “Music in

Colonial America,” Revolutionary War

Journal (21 August 2014).

Sharp, Bartholomew. Voyages

and Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp. P. A.

Esq., 1684.

Snelders, Stephen. “Smoke on

the Water: Tobacco, Pirates, and Seafaring

in the Early Modern World,” Intoxicating

Spaces: The Impact of New Intoxicants on Urban

Spaces in Europe, 1600-1850 (9 December

2019).

Snelgrave, William. A

New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, and the

Slave Trade. London: James, John, and Paul

Knapton, 1734.

Struzinski, Steven. “The

Tavern in Colonial America,” The

Gettysburg Historical Journal volume 1,

article 7 (2002), 29-38.

Sutton, Angela C. Pirates

of the Slave Trade: The Battle of Cape Lopez and

the Birth of an American Institution.

Prometheus, 2023.

Talty, Stephan. Empire of Blue Water: Captain

Morgan’s Great Pirate Army, the Epic Battle for

the Americas, and the Catastrophe That Ended the

Outlaws’ Bloody Reign. Crown, 2007.

Thomson, Keith. Born

To Be Hanged: The Epic Story of the Gentlemen

Pirates Who Raided the South Seas, Rescued a

Princess, and Stole a Fortune. Little,

Brown, 2022.

Todd. “Daily

Life of the American Colonies: The Role of

the Tavern in Society,” The Witchery Arts

(3 April 2015).

Todd, Janet. “Carleton,

Mary (1634x42-1673),” Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography. Oxford University, 2004.

The

Tryals of Captain John Rackham, and Other

Pirates. Jamaica: Robert Baldwin,

1721.

The

Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other

Pirates. London: Benj. Cowse, 1719.

“Tryals of Thirty-six

Persons for Piracy” in British Piracy in the

Golden Age: History and Interpretation,

1660-1730 edited by Joel H. Baer. Pickering

& Chatto, 2007, 3:167-192.

Turner, John. Sufferings

of John Turner, Chief Mate of the Country

Ship, Tay. Thomas Tegg, 1810.

Vallar, Cindy. “Pirates

and Music,” Pirates and Privateers

(18 September 2013).

Watson, John F. Annals

of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden

Time, vol. 2. John Penington and Uriah

Hunt, 1844.

Wafer, Lionel. A New

Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of

America. London: James Knapton, 1699.

Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U.,

and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard’s

Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen

Anne’s Revenge. University of North Carolina,

2018.

Winstead, Dave. “1/24/2024

Is ‘Eat, Drink, And Be Merry’ A Biblical

Concept?” FaithByTheWord (24 January

2024).

Yates, Donald. “Colonial

Drinks, 1640-1860,” Bottles and Extras

(Summer 2003), 39-41.

While I worked on

this article, my father passed away.

He shared his affinity for the water

and boats with me in my youth, which

helped awaken a desire to write about

pirates. This article is for him. Now

that you are at peace and without

pain, Dad, may you eat, drink, and be

merry.

Lee Aker

Rest in peace |

Copyright ©2024 Cindy

Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |