Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

In Memoriam

Lady Luck and Other Amusements

by Cindy Vallar

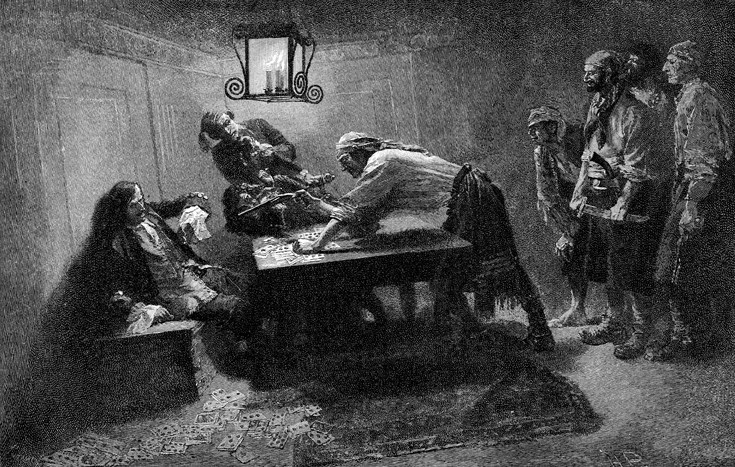

Card game interrupted

"Capture of the Galleon" by Howard Pyle, 1887

(Source: Dover's Pirates)

Drinking

and eating were not the only ways in which pirates

had fun. They also enjoyed gaming, an old word for

gambling. Just like the drinking of spirits, there

was a danger for both ship and crew if the pirates

did so at sea because tempers could flare for those

upon whom Lady Luck did not shine. Since teamwork

was essential, the pirates often had something to

say about gambling in their articles of agreement.

One item that Captain

Peter Solgard of HMS Greyhound discovered

aboard Charles Harris’s ship was the code under

which Edward Low

sailed. The proceedings of the trials that resulted

in convictions for Harris and twenty-six others was

printed by Samuel

Kneeland in 1723, and included the captured Articles of

Agreement. The fifth one was

He that

shall be found Guilty of Gaming, or playing at

Cards, or Defrauding or Cheating one another to

the Value of a Royal Plate, shall suffer what

Punishment the Captain and majority of the

Company shall think fit. (Tryals of

Thirty-six, 3:191)

Bartholomew Roberts’s

code forbade playing cards or dice if gambling for

money was involved. A specific punishment wasn’t

given, but the articles agreed upon by the pirates

aboard John Phillips’ ship did.

If any Man

shall steal any Thing in the Company, or game to

the Value of a Piece of Eight, he shall be

maroon’d or shot. (Defoe, 342)

But playing on land was

another matter. Gambling could involve cards, dice,

or almost any object a pirate could think to wager

on.

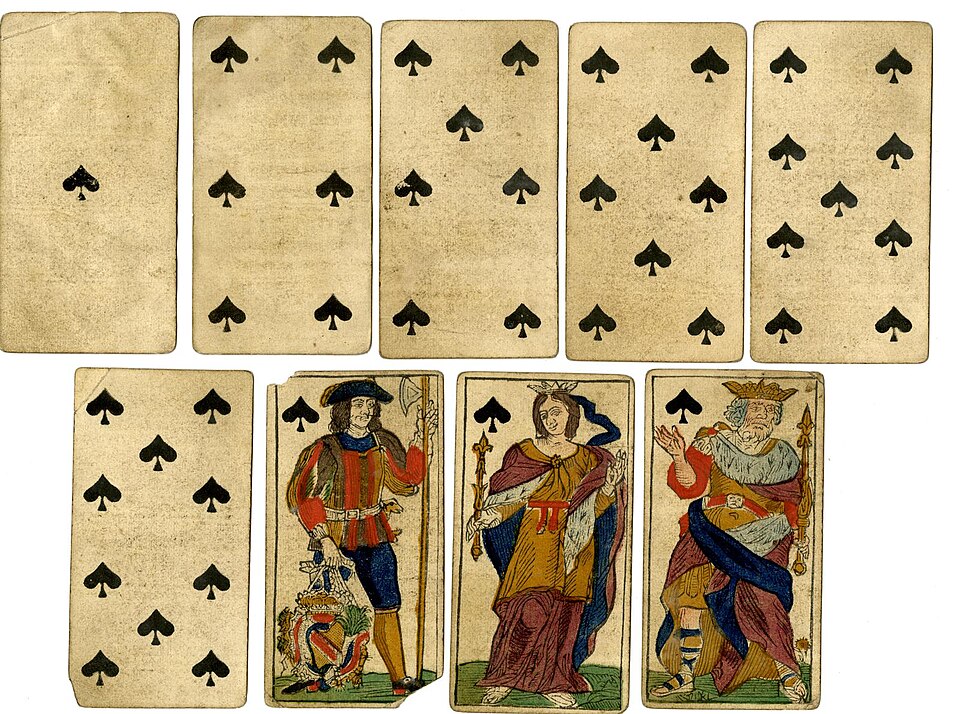

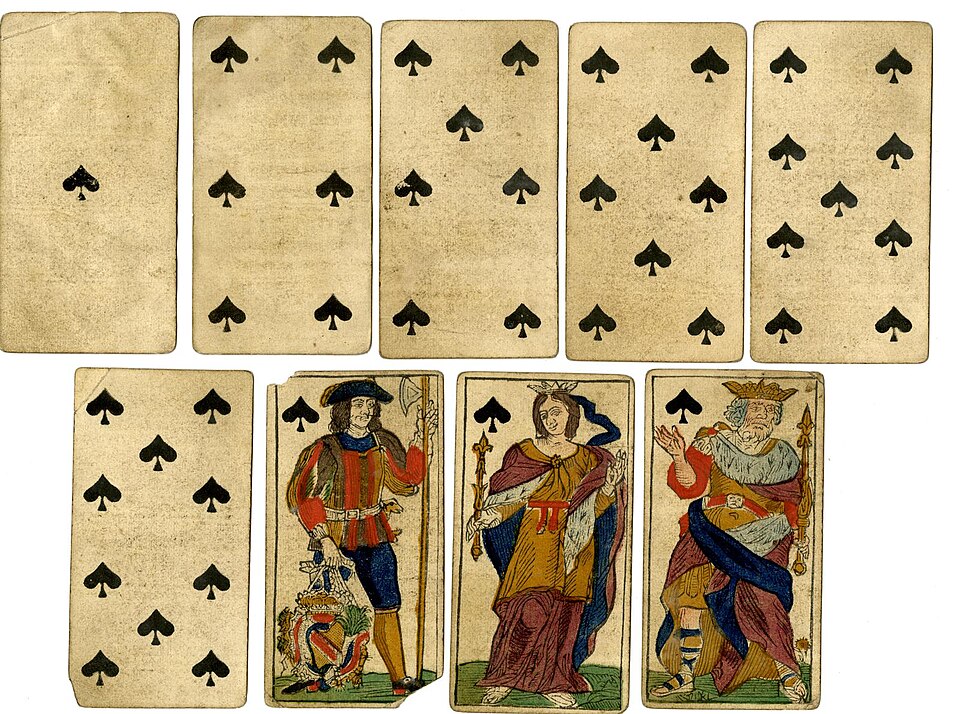

Cards

of the past differed from cards used today. Those

that pirates played with didn’t have numbers on

them. The standard deck during the buccaneering era

was known as the “French” deck. It was comprised of

fifty-two cards and four suits (clubs, diamonds,

hearts, and spades). The kings, queens, and jacks or

knaves were single faces, rather than having the

figure on one end and the mirror opposite on the

other. The remaining cards merely showed the suits.

(For example, the ten of spades just had ten spades

on it. A two of hearts had only two hearts but no

numbers on it.) Another difference was the size of

the cards. They were larger and players needed both

hands to hold them. Cards

of the past differed from cards used today. Those

that pirates played with didn’t have numbers on

them. The standard deck during the buccaneering era

was known as the “French” deck. It was comprised of

fifty-two cards and four suits (clubs, diamonds,

hearts, and spades). The kings, queens, and jacks or

knaves were single faces, rather than having the

figure on one end and the mirror opposite on the

other. The remaining cards merely showed the suits.

(For example, the ten of spades just had ten spades

on it. A two of hearts had only two hearts but no

numbers on it.) Another difference was the size of

the cards. They were larger and players needed both

hands to hold them.

Pirates had their choice when it came to specific

games to play with the cards. L’Ombre

had several variations. The primary version was

“called Renegado, at which three only can play, to

whom are dealt Nine Cards apiece.” (Cotton, 72) Aluette,

also known as La Vache (the cow), was

popular among French buccaneers and required a

special deck of forty-eight cards to play. Other

popular card games included All-Fours, Ruff and

Honours (also known as Slamm), Bone-Ace,

Lanterloo,

Maws (a

favorite since William Shakespeare’s days), Noddy

(a forerunner of cribbage), and One-and-Thirty

(similar to blackjack except the goal was to reach

thirty-one rather than twenty-one). Samuel

Bellamy and Paulsgrave Williams were known to

play cards, backgammon, and checkers.

As

for dice, Hazard

“speedily makes a Man or undoes him; in the

twinkling of an eye either a Man or a Mouse.” It was

“play’d but with two Dice, but there may play at it

as many as can stand round the largest round Table.”

(Cotton, 122) It was addictive, “for when a man

begins to play he knows not when to leave off; and

having once accustom’d himself to play at Hazzard,

he hardly ever after minds any thing else . . . .”

(Cotton, 125) As

for dice, Hazard

“speedily makes a Man or undoes him; in the

twinkling of an eye either a Man or a Mouse.” It was

“play’d but with two Dice, but there may play at it

as many as can stand round the largest round Table.”

(Cotton, 122) It was addictive, “for when a man

begins to play he knows not when to leave off; and

having once accustom’d himself to play at Hazzard,

he hardly ever after minds any thing else . . . .”

(Cotton, 125)

Those who liked to take chances, deceive others, and

play the odds might partake of a game of Liar’s Dice,

which involved dice and cups. French buccaneers

liked to play passe-dix, which their English

counterparts referred to as “passage.”

Two players, such as Sieur Michel de Grammont (a

buccaneer captain) and Jean d’Estrées (a French

count and an admiral in la marine royale),

played on Petit-Goâve. They took turns throwing

three dice, and needed a score greater than ten to

win.

Board games were also popular. One involving dice

was Goose,

which was invented in Italy and gifted to the

Spanish king. An ancient strategy game that remained

popular was Nine Men’s

Morris. It could be played on a board, or any

surface on which the board could be drawn. French

pirates enjoyed playing Shut the

Box; other pirates played Sweat Bloth, where a

bandana served as the board.

When recovering artifacts from Blackbeard’s Queen

Anne’s Revenge and Sam Bellamy’s Whydah,

marine archaeologists found

a few lead

pieces flattened and shaped into gaming

chips of square or round shapes. Six

square-shaped pieces weigh between 12 and 32

grams, and two are incised with an X on one

face. One of those was done using the

wrigglework technique similar to that seen on

cannon aprons. Dozens of similarly shaped and

scored gaming pieces were found on the pirate

ship Whydah. Checkers, sennet, and

draughts were popular board games of this era.

(Wilde-Ramsing, 139)

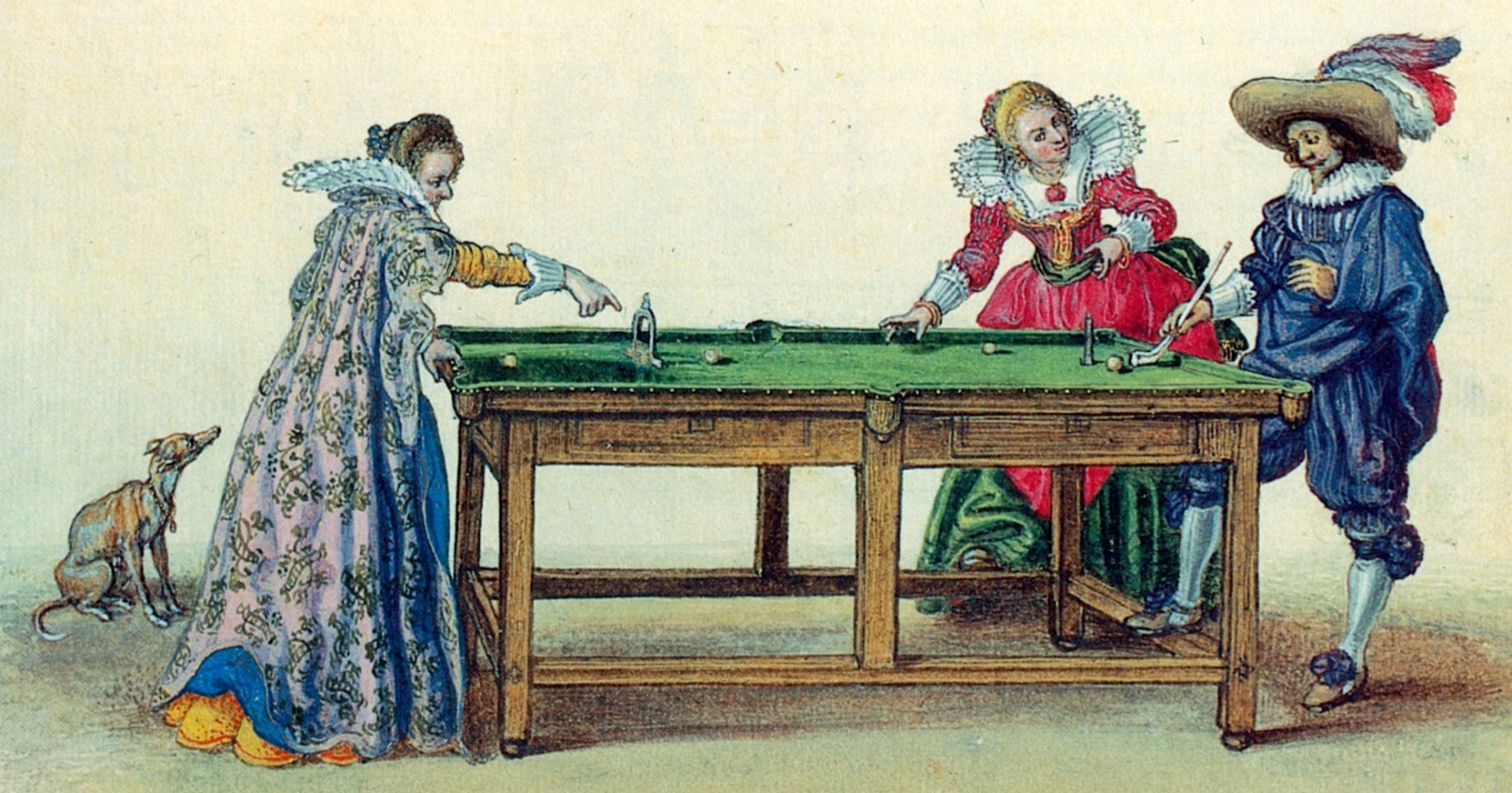

Billiards

was also a popular pastime, especially during the

time of the buccaneers. Several Port Royal taverns,

such as the George and the Feathers, had separate

rooms where this game was played.

Many of the games that Asian pirates (men, women,

and children) played involved wagering. Players of fan-tan had to guess

how many coins, beans, or some other objects

remained after the pile was disseminated by fours. Mahjong

and quail fighting were also popular. Gambling

allowed the pirates to add to their ill-gotten

gains, but losers often hocked their clothes just to

keep playing. For some, the habit was even worse, as

shown in this boatwoman’s song:

Oh Heaven!

Why I am a gambler’s wife I simply cannot see,

For a gambler is

a man of very low degree;

Other people are

happy and gay,

But he roams in

the gambling den all day;

He goes and

leaves me many a lonely night,

When I wake up

he is out of sight;

Three girls are

sold into slavery by thee,

Your patrimony

is wasted I clearly foresee. (Antony,

145-146)

It wasn’t just money that

was wagered. Some games involved drinking. One group

of pirates bet on how much each could drink. They

became so inebriated that they lost consciousness,

which allowed their captives to gain the upper hand.

One lesson that Chinese pirates taught to new

recruits was to show no fear when danger threatened.

In 1809, Richard

Glasspoole spent three months as the “guest”

of Chinese pirates and witnessed one such incident.

[W]hilst

the Ladrone fleet was receiving a distant

cannonade from the Portuguese and Chinese, the

men were playing cards upon deck, and in a group

so amusing themselves, one man was killed by a

cannon shot; but the rest, after putting the

mangled body out of the way, went on with their

game, as if nothing of the kind had happened.

(Further, 45)

In Asia, religious

festivals broke the monotony of everyday life. The

pirates could relax and, if on land, enjoy parades

and performances such as dramas, comedies, and

puppet shows. They might sing or dance, or renew old

friendships.

Singing and storytelling were universal

entertainments. Although books made good cannon

fodder on most pirate ships or were deemed of no use

and tossed overboard, a few pirates liked to read.

Among the items that Stede

Bonnet took with him when he boarded Revenge

was a library. So did Guo Podai, who liked to

read poetry and historical romances.

Musicians gave concerts or accompanied mates who

sang familiar songs.

“Ballads and bawdy drinking songs . . . told stories

of love, adventures, battles, political strife, and

humorous tales.” (Schenawolf) Also popular were

religious songs. Some pirates enjoyed singing some

of the ballads

written about their fellow marauders of the sea,

such as Henry Every

and Blackbeard.

One of the articles under which those who followed

Bartholomew Roberts sailed pertained to music.

The

Musicians to have Rest on the Sabbath Day, but

the other six Days and Nights, none without

special Favour. (Defoe, 212)

In essence, those who

played an instrument didn’t have to play on Sunday,

but if martial airs were required to instill a

fighting spirit in the men, or if the men simply

wanted to be entertained, the musicians were

expected to do so any time of the day or night. In

the fall of 1721, Roberts and his men captured a

French warship. One captive was the governor of

Martinique, who had dared to pursue Roberts rather

than submit to his earlier demands. Such defiance

deserved punishment in the eyes of the pirates, so

the governor ended up swinging from a yardarm “while

the crew drank their fill of plundered spirits and

took turns dancing to the tunes of the exhausted

musicians tooting dented brass instruments.”

(Sutton, 81)

For some, having plunder filling their pockets

allowed them to go shopping. Clothes, hats, shoes,

and guns, as well as pipes of ivory, pewter, or red

clay, were favorite purchases. Their wealth

permitted them to buy what they otherwise would

never have afforded. To their way of thinking if

someone of the upper-crust could buy it, so could

they.

Then there were the temptations of the flesh and

seductions of escape . . . but those are topics for

another day.

. . . To be continued

Resources:

“America

and West Indies: March 1678,’ in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 10,1677-1680 edited by W.

Noel Sainsbury and J. W. Fortescue. London, 1896,

220-231 (March-Sept. St. Christopher’s. 645.)

“America

and West Indies: August 1698, 22-25,’ in Calendar

of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume 16,1697-1698 edited by J. W.

Fortescue. London, 1905, 399-406 (Aug. 25. 771.).

“America

and West Indies: June 1718,” in Calendar of

State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies:

Volume 30, 1717-1718 edited by Cecil Headlam.

London, 1930, 264-287. (June 18. Charles Towne,

South Carolina. 556.).

Andrade, Tonio.

Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China’s First

Great Victory Over the West. Princeton,

2011.

Antony, Robert J. Like

Froth Floating on the Sea: The World of Pirates

and Seafarers in Late Imperial China.

Institute of East Asian Studies, University of

California Berkley, 2003.

Appleby, John C. Women

and English Piracy 1540-1720: Partners and

Victims of Crime. Boydell, 2013.

Ashmead, Henry Graham.

History

of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. L.

H. Everts & Co., 1884.

Bahadur, Jay. The Pirates of Somalia: Inside

Their Hidden World. Pantheon Books, 2011.

Bialuschewski, Arne. Raiders

and Natives: Cross-cultural Relations in the Age

of Buccaneers. University of Georgia, 2022.

Bold in Her

Breeches: Women Prostitutes Across the Ages

edited by Jo Stanley. Pandora, 1996.

Borvo, Alain. “Discover

Aluette, the Game of the Cow,” Traditional

Tarot (21 July 2021).

Bradley, Peter T. Pirates

on the Coasts of Peru 1598-1701.

Independently published, 2008.

Brooks, Baylus C. Quest

for Blackbeard: The True Story of Edward Thache

and His World. Independently published,

2016.

Brown, Edward. A

Seaman’s Narrative of the Adventures During a

Captivity Among Chinese Pirates, on the Coast

of Cochin-China. Charles Westerton,

1861.

Burg, B. R. “The

Buccaneer Community” in Bandits at Sea: A

Pirates Reader edited by C. R. Pennell. New

York University, 2001, 211-243.

Choundas, George. The Pirate Primer: Mastering

the Language of Swashbucklers and Rogues.

Writer’s Digest, 2007.

Codfield, Rod. “Tavern

Tales: 1708 Letter,” Historic London

Town & Gardens (2 April 2020).

Cotton, Charles. The

Compleat Gamester. London: Charles Brome,

1710.

Croce, Pat. The

Pirate Handbook. Chronicle Books, 2011.

Dampier, William. A New

Voyage Round the World vol. 1. London:

James Knapton, 1699.

Defoe, Daniel. A

General History of the Pyrates edited by

Manuel Schonhorn. Dover, 1999.

Duffus, Kevin P. The

Last Days of Black Beard the Pirate. Looking

Glass Productions, 2008.

Eastman, Tamara J., and Constance Bond. The

Pirate Trial of Anne Bonny and Mary Read.

Fern Canyon Press, 2000.

Ellms, Charles. The

Pirates Own Book. 1837.

Esquemeling, John. The Buccaneers of America.

Rio Grande Press, 1684.

Exquemelin, Alexander

O. The Buccaneers of America translated by

Alexis Brown. Dover, 1969.

“FAQs:

Beverages,” Food Timeline edited by

Lynne Olver (30 November 2021).

Ford, Michael. “The

Attack of the ‘Last Great Pirate’ – Benito De

Soto, Wellington’s Treasure and the Raid of the

‘Morning Star,’ Military History Now

(21 June 2020).

Ford, Michael E. A. Hunting

the Last Great Pirate: Benito de Soto and the

Rape of the Morning Star. Pen & Sword,

2020.

A Full

and Exact Account of the Tryal of the Pyrates

Lately Taken by Captain Ogle. London:

J. Roberts, 1723.

Further

State of the Ladrones on the Coast of China.

Lane, Darling, and Co., 1812.

Geanacopulos, Daphne Palmer. The Pirate Next

Door: The Untold Story of Eighteenth Century

Pirates’ Wives, Families and Communities.

Carolina Academic, 2017.

Gosse, Philip. The Pirates’ Who’s Who. Rio

Grande Press, 1924.

Gutzlaff,

Charles. Three

Voyages Along the Coast of China in 1831,

1832, & 1833. Frederick, Westley

and A. H. Davis, 1834.

Hacke, William. Collection

of Original Voyages. London: James

Knapton, 1699.

Hailwood, Mark. “‘Come

hear this ditty’: Seventeenth-century

Drinking Songs and the Challenges of Hearing the

Past,” The Appendix (10 July 2013).

Hardy, Thomas. “Drinking

Song,” Poetry Nook.

Hartsmar, Markus. “Oscar

Wilde, 1854-1900,” Absinthe.se.

Hughes, Ben. Apocalypse

1692: Empire, Slavery, and the Great Port Royal

Earthquake. Westholme, 2017.

Jacob, Robert. “Popular

Games from the Golden Age!” Robert Jacob.

Jamaica Rose. “Games

Pirates Played,” Pirates Magazine (Summer

2006), 53-55.

Jamaica Rose. “Pirate

Pastimes & Pleasures,” Pirates Magazine

(Summer 2006), 49-51.

Jameson, John Franklin.

Privateering

and Piracy in the Colonial Period:

Illustrative Documents. Macmillan, 1923.

Johnson, Charles. A General

History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most

Notorious Pyrates. London: C. Rivington,

1724.

Kehoe, M. “Booze,

Sailors, Pirates and Health in the Golden Age of

Piracy,” The Pirate Surgeon’s Journals:

Tools and Procedures.

Kehoe, M. “Christmas

Holidays at Sea in the Golden Age of Piracy,”

The Pirate Surgeon’s Journals: Tools and

Procedures.

Kehoe, Mark C. “Fresh

Water at Sea in the Golden Age of Piracy,” The

Pirate Surgeon’s Journals.

Kehoe, M. “Tobacco

and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy,”

The Pirate Surgeon’s Journals: Tools and

Procedures.

Kelleher, Connie. The

Alliance of Pirates: Ireland and Atlantic Piracy

in the Early Seventeenth Century. Cork

University, 2020.

King

James Bible Online.

Labat, Jean-Baptiste. The

Memoirs of Père Labat, 1693-1705

translated and abridged by John Eaden.

Routledge, 2013.

Lane, Kris E. Pillaging the Empire:

Piracy in the Americas, 1500-1750. M. E.

Sharpe, 1998.

Lee, Robert E. Blackbeard

the Pirate: A Reappraisal of His Life and Times.

John F. Blair, 2002.

“Liar’s

Dice,” Awesome Dice.

Little, Benerson. The

Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish

Main, 1674-1688. Potomac Books, 2007.

Little, Benerson. “Of

Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar

Smoking Women,” Swordplay &

Swashbucklers (1 January 2017).

Little, Benerson. The

Sea Rover’s Practice: Pirate Tactics and

Techniques, 1630-1730. Potomac Books, 2005.

Marley, David F. Pirates of the Americas

Volume 1 1650-1685. ABC Clio, 2010.

Marley, David F. Pirates

of the Americas Volume 2 1686-1725. ABC

Clio, 2010.

Mather, Increase. Wo to

Drunkards (second edition). Boston:

Timothy Green, 1712.

McAlister, Zac. “What Is

Black Strap Rum,” Booze Bureau.

Neumman, Charles Fried. History

of the Pirates Who Infested the China Sea,

from 1807 to 1810. Oriental

Translation Fund, 1831.

Parlett, David. “Historic

Card Games,” Games & Gamebooks.

2022.

Pawson, Michael, and

David Buisseret. Port Royal, Jamaica.

University of the West Indies, 2000.

“Pirate

Potheads? On Drugs and Tobacco in the Golden Age

of Piracy,” Gold and Gunpowder (8

December 2023).

The Pirate’s

Pocket-Book edited by Stuart Roberston.

Conway, 2008.

Pirates in Their Own

Words: Eye-witness Accounts of the ‘Golden Age’

of Piracy, 1690-1728 edited by E. T. Fox.

Fox Historical, 2014.

“The Plank

House,” The Marcus Hook Preservation

Society.

Preston, Diana and

Michael. A Pirate of Exquisite Mind: Explorer,

Naturalist, and Buccaneer: The Life of William

Dampier. Walker & Co., 2004.

Pruitt, Sarah. “How

Christmas Was Celebrated in the 13 Colonies,”

History (5 October 2023).

Rogers, Woodes. A

Cruising Voyage Round the World.

Cassell and Company, 1928.

Sanders, Richard. If a Pirate I must be . . .

: The True Story of “Black Bart,” King of the

Caribbean Pirates. Skyhorse, 2007.

Sanna, Antonio.

“Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum”: Representations of

Drunkenness in Literary and Cinematic Narratives

on Pirates,” Pirates in History and Popular

Culture edited by Antonio Sanna. McFarland,

2018, 120-131.

Schenawolf, Harry. “Music in

Colonial America,” Revolutionary War

Journal (21 August 2014).

Sharp, Bartholomew. Voyages

and Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp. P. A.

Esq., 1684.

Snelders, Stephen. “Smoke on

the Water: Tobacco, Pirates, and Seafaring

in the Early Modern World,” Intoxicating

Spaces: The Impact of New Intoxicants on Urban

Spaces in Europe, 1600-1850 (9 December

2019).

Snelgrave, William. A

New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, and the

Slave Trade. London: James, John, and Paul

Knapton, 1734.

Struzinski, Steven. “The

Tavern in Colonial America,” The

Gettysburg Historical Journal volume 1,

article 7 (2002), 29-38.

Sutton, Angela C. Pirates

of the Slave Trade: The Battle of Cape Lopez and

the Birth of an American Institution.

Prometheus, 2023.

Talty, Stephan. Empire of Blue Water: Captain

Morgan’s Great Pirate Army, the Epic Battle for

the Americas, and the Catastrophe That Ended the

Outlaws’ Bloody Reign. Crown, 2007.

Thomson, Keith. Born

To Be Hanged: The Epic Story of the Gentlemen

Pirates Who Raided the South Seas, Rescued a

Princess, and Stole a Fortune. Little,

Brown, 2022.

Todd. “Daily

Life of the American Colonies: The Role of

the Tavern in Society,” The Witchery Arts

(3 April 2015).

Todd, Janet. “Carleton,

Mary (1634x42-1673),” Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography. Oxford University, 2004.

The

Tryals of Captain John Rackham, and Other

Pirates. Jamaica: Robert Baldwin,

1721.

The

Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other

Pirates. London: Benj. Cowse, 1719.

“Tryals of Thirty-six

Persons for Piracy” in British Piracy in the

Golden Age: History and Interpretation,

1660-1730 edited by Joel H. Baer. Pickering

& Chatto, 2007, 3:167-192.

Turner, John. Sufferings

of John Turner, Chief Mate of the Country

Ship, Tay. Thomas Tegg, 1810.

Vallar, Cindy. “Pirates

and Music,” Pirates and Privateers

(18 September 2013).

Watson, John F. Annals

of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden

Time, vol. 2. John Penington and Uriah

Hunt, 1844.

Wafer, Lionel. A New

Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of

America. London: James Knapton, 1699.

Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U.,

and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard’s

Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen

Anne’s Revenge. University of North Carolina,

2018.

Winstead, Dave. “1/24/2024

Is ‘Eat, Drink, And Be Merry’ A Biblical

Concept?” FaithByTheWord (24 January

2024).

Yates, Donald. “Colonial

Drinks, 1640-1860,” Bottles and Extras

(Summer 2003), 39-41.

While I worked on

this article, my father passed away.

He shared his affinity for the water

and boats with me in my youth, which

helped awaken a desire to write about

pirates. This article is for him. Now

that you are at peace and without

pain, Dad, may you eat, drink, and be

merry.

Lee Aker

Rest in peace |

Copyright ©2024 Cindy

Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |

Cards

of the past differed from cards used today. Those

that pirates played with didn’t have numbers on

them. The standard deck during the buccaneering era

was known as the “French” deck. It was comprised of

fifty-two cards and four suits (clubs, diamonds,

hearts, and spades). The kings, queens, and jacks or

knaves were single faces, rather than having the

figure on one end and the mirror opposite on the

other. The remaining cards merely showed the suits.

(For example, the ten of spades just had ten spades

on it. A two of hearts had only two hearts but no

numbers on it.) Another difference was the size of

the cards. They were larger and players needed both

hands to hold them.

Cards

of the past differed from cards used today. Those

that pirates played with didn’t have numbers on

them. The standard deck during the buccaneering era

was known as the “French” deck. It was comprised of

fifty-two cards and four suits (clubs, diamonds,

hearts, and spades). The kings, queens, and jacks or

knaves were single faces, rather than having the

figure on one end and the mirror opposite on the

other. The remaining cards merely showed the suits.

(For example, the ten of spades just had ten spades

on it. A two of hearts had only two hearts but no

numbers on it.) Another difference was the size of

the cards. They were larger and players needed both

hands to hold them.  As

for dice,

As

for dice,