Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Pirates and

Death

by Cindy Vallar

Perhaps Bartholomew

Roberts best summed up a pirate’s life while

speaking to new recruits forced to join his crew:

In an

honest Service there is thin Commons, low Wages,

and hard Labour; in this, Plenty and Saiety,

Pleasure and Ease, Liberty and Power; and who

would not ballance Creditor on this Side, when

all the Hazard that is run for it, at worst, is

only a sower Look or two at choaking. No, a

merry Life and a short one, shall be my Motto.

(Defoe, 244)

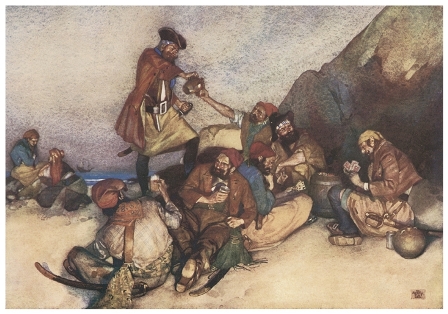

Pirate life versus navy life

(Source: Dover)

As Marcus

Rediker explained in the introduction to Between

the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, “[t]he

omnipotence of the elements and the fragility of

human life marked the consciousness of every

early-eighteenth-century seaman.” (2) They lived

with death every day, not just from nature, but also

from the work they did. Many pirates initially came

from this legitimate maritime world and were all too

familiar with the hazards seamen encountered. Rather

than heed orders from the master of a ship, they

preferred to sail aboard a vessel where they were

masters of their fates – at least as much as Mother

Nature permitted. This was why Roberts preferred to

enjoy life for as long as he was able. As with most

choices, his had a consequence that proved fatal.

Sailing on a wooden ship was similar to running the

gauntlet. Rather than enduring strikes from clubs,

swords, or other items that inflicted pain, seamen

encountered churning seas, sudden squalls,

hurricanes, waterspouts, or any number of other

tempests at Mother Nature’s disposal, including

unseen shoals and reefs that could wreck the ship.

Then there were the inevitable problems that

resulted from poor maintenance, such as a leaky

hull, and the inherent dangers of working on a ship.

[T]he

chances of a seaman ending his life in . . . a

catastrophe were high, and many a man fell from

the rigging, was washed overboard, or was

fatally struck by falling gear. (Rediker,

Between, 92-93)

Ship explosion and waterspouts

One such catastrophe occurred on 2 January 1669. Henry

Morgan summoned the buccaneer captains to

gather at Île à Vache to plot out another raid on

Spanish America. They chose Cartagena

as their next target, and fifteen guns were fired to

announce their destination to the rest of the

pirates. Then the captains, including Morgan, dined

on the flagship’s quarterdeck. Richard Browne, a surgeon,

later wrote:

But

about 12 o’clock . . . the Oxford

blew up and above 200 men lost . . . There were

but six men and four boys that belonged to the

Oxford saved . . . and eight more that were

aboard the French prize, some few a-hunting, and

others washing their clothes ashore. It cannot

be imagined how this sad accident happened, but

suppose the negligence of the gunner in filling

powder to load the guns . . . At the time of the

blowing up the ship, Captain Whiting, the

purser, and myself were at dinner at the

binnacle . . . The mainmast jumped up out of the

ship and fell upon the starboard quarter, where

Captain Aylett, Captain Bigford, and some other

Captains were walking and were all knocked on

the head by the mainmast, and Captain Whiting,

who was on my right hand and the purser on my

left, and was out-angled in the awning and so

drowned. . . . I only heard a great rushing

noise, with fire and smoke, and the battlements

of the awning being on fire fell upon me, and

immediately I felt the deck give way and was in

the water over head and dived, and presently

bore up again and saved myself by getting

astride upon the mizzenmast. There were not

above 20 persons . . . from other ships and our

own company that were saved, and most of them

much hurt. All them that were upon deck or any

part of the ship, were all lost, except those

upon the quarter-deck. (Marley, Pirates,

1:427-428)

Other times Mother Nature, rather

than human error, caused the accidental deaths of

men. While traversing the Darien

jungle with other buccaneers in 1681, George Gainy

(Gayny) drowned when he attempted to cross a river

with a bag containing 300 Spanish silver dollars

draped around his neck. Lionel

Wafer, one of the surgeons on the expedition,

discovered his body after it finally washed ashore

in a creek. That same year, John Alexander went

under while transporting tools to the island of

Chira. It took three days to find the body of this

Scot, who sailed with Bartholomew

Sharp. The next day, the buccaneers “threw him

overboard, giving him three French vollies for his

customary ceremony.” (Gosse, 28) Henry Sherral

(Shergall) fell into the sea from the spritsail-top

of Sharp’s ship near Cape Horn in October 1681,

never to be seen again. Edward Church and a man

named Atwell (Atwill), who sailed with Charles

Gibbs, drowned off the coast of Rhode Island

in 1831. The circumstances surrounding their deaths

weren’t recorded, but they were far from the only

pirates who died mysteriously while at sea. The best

leader of the flibustiers from France, le Chevalier

de Grammont, and nearly 200 men perished

during a storm in 1686. Swept overboard in dirty

weather, Captain Stephen Heynes, whose brutal

torture techniques caused his own crew to beg him to

stop, lost his life in 1582. Zheng Yi

(Cheng I) went overboard during a storm in 1807, at

the height of his power as leader of a confederation

of Chinese pirates. Other times Mother Nature, rather

than human error, caused the accidental deaths of

men. While traversing the Darien

jungle with other buccaneers in 1681, George Gainy

(Gayny) drowned when he attempted to cross a river

with a bag containing 300 Spanish silver dollars

draped around his neck. Lionel

Wafer, one of the surgeons on the expedition,

discovered his body after it finally washed ashore

in a creek. That same year, John Alexander went

under while transporting tools to the island of

Chira. It took three days to find the body of this

Scot, who sailed with Bartholomew

Sharp. The next day, the buccaneers “threw him

overboard, giving him three French vollies for his

customary ceremony.” (Gosse, 28) Henry Sherral

(Shergall) fell into the sea from the spritsail-top

of Sharp’s ship near Cape Horn in October 1681,

never to be seen again. Edward Church and a man

named Atwell (Atwill), who sailed with Charles

Gibbs, drowned off the coast of Rhode Island

in 1831. The circumstances surrounding their deaths

weren’t recorded, but they were far from the only

pirates who died mysteriously while at sea. The best

leader of the flibustiers from France, le Chevalier

de Grammont, and nearly 200 men perished

during a storm in 1686. Swept overboard in dirty

weather, Captain Stephen Heynes, whose brutal

torture techniques caused his own crew to beg him to

stop, lost his life in 1582. Zheng Yi

(Cheng I) went overboard during a storm in 1807, at

the height of his power as leader of a confederation

of Chinese pirates.

Benjamin

Hornigold, who taught many others the fine art

of piracy, took the King’s Grace and became a pirate

hunter. On one voyage to capture rogues who refused

to change their ways, his ship struck a reef and he

drowned.1 The

most legendary of the pirate shipwrecks was the Whydah,

and her captain, Samuel

Bellamy, was once a protégé of

Hornigold’s.

The Whydah

began a slow turn toward the wind, taking

thousands of tons of water over the gunwales as

she was swept by forty-foot waves. Many of the

148 men on board must have been swept over the

side at this point. The ones who weren’t had

probably taken refuge in the hold or were

clinging desperately to the rigging, where the

wind was colder than the forty-degree water. The Whydah

began a slow turn toward the wind, taking

thousands of tons of water over the gunwales as

she was swept by forty-foot waves. Many of the

148 men on board must have been swept over the

side at this point. The ones who weren’t had

probably taken refuge in the hold or were

clinging desperately to the rigging, where the

wind was colder than the forty-degree water.

Still the ship

turned. . . . Then came the fateful bump that

meant the stern had run aground and the ship

could turn no more. More water swept the deck,

filling the holds and slowly rolling the ship.

Within fifteen minutes of striking land, the

mainmast was snapped off and floated free. Then,

with nothing left to keep her upright, the ship

began to roll upside down. Pirates were crushed

as cannons and goods stored below came crashing

through the decks. Those who could, swam, but in

water so cold, there were few who could make it

the five hundred feet to shore. Those who did

froze to death trying to climb the steep sand

cliffs of Eastham. (Clifford, Expedition,

265)

One hundred thirty

pirates lost their lives that night off the coast of

Cape Cod on 26 April 1717, including Bellamy. A

cannon pinned the youngest

member of the crew, John King,

to the ocean floor. Centuries later, after Barry

Clifford discovered the remains of the wreck, all

that remained of the nine year old was a fragment of

leg bone, concealed in the same silk stocking he had

worn the day Bellamy captured the ship John sailed

on with his mother, and his leather shoe still

fastened with its buckle.

In spite of all these potentially fatal threats,

other more pervasive dangers claimed the lives of

more pirates and seamen than any other cause of

death. When Commodore George

Anson left Portsmouth in 1740, 1,995 men

served aboard the seven naval ships. Four years

later on his return, he had only one ship and 145

men. More than 53% of his contingent had died from

illness, particularly scurvy.2 During

the Seven

Years’ War, 1,500 men in the Royal Navy were

killed in action, whereas almost 15,000 succumbed to

disease.

Before

Francis

Drake captured the mules laden with treasure

bound for Nombre de

Dios (1572), his brother Joseph died in his

arms from an epidemic that swept through his crew.

Francis demanded the surgeon perform an autopsy to

determine the cause of death in hopes of saving

others afflicted with the malady. Joseph’s liver was

swollen and his heart “sodden,” but before the

surgeon gave his diagnosis, he succumbed also.

Period documents identified the disease

as calenture – delirium, fever, and sunstroke – but

yellow fever was a likely culprit. Sir Francis would

also die of an illness, dysentery, while on his last

voyage in 1596. John Ward

(Yusuf Reis) died of the plague in 1623, in his

adopted homeland of Tunis, where he had lived since

becoming a renegado and joining the Barbary

corsairs. William Cammock, one of Bartholomew

Sharp’s buccaneers, imbibed so much while at La

Serena that he contracted a malignant fever and

hiccoughs, which killed him in 1679/1680. Captain

John Cooke (Cook) fell ill and died in 1684. This

buccaneer, who also sailed with Sharp as well as

Charles Swan, was laid to rest ashore at Cape

Blanco, Mexico. Another cohort of Sharp’s was his

chief mate, John Hilliard, who became a victim of

dropsy in 1681. Sharp recorded in his journal the

death of another of his crew in January 1682.

William Stephens (Stevens) “was observed, after his

eating of three Manchaneel

Apples, at King Charles’ Harbour, to waste

away strangely, till at length he was become a

perfect skeleton.” (Downie, 218) “Next morning we

threw overboard our dead man and gave him two French

vollies and one English one.” (Gosse, 218) Before

Francis

Drake captured the mules laden with treasure

bound for Nombre de

Dios (1572), his brother Joseph died in his

arms from an epidemic that swept through his crew.

Francis demanded the surgeon perform an autopsy to

determine the cause of death in hopes of saving

others afflicted with the malady. Joseph’s liver was

swollen and his heart “sodden,” but before the

surgeon gave his diagnosis, he succumbed also.

Period documents identified the disease

as calenture – delirium, fever, and sunstroke – but

yellow fever was a likely culprit. Sir Francis would

also die of an illness, dysentery, while on his last

voyage in 1596. John Ward

(Yusuf Reis) died of the plague in 1623, in his

adopted homeland of Tunis, where he had lived since

becoming a renegado and joining the Barbary

corsairs. William Cammock, one of Bartholomew

Sharp’s buccaneers, imbibed so much while at La

Serena that he contracted a malignant fever and

hiccoughs, which killed him in 1679/1680. Captain

John Cooke (Cook) fell ill and died in 1684. This

buccaneer, who also sailed with Sharp as well as

Charles Swan, was laid to rest ashore at Cape

Blanco, Mexico. Another cohort of Sharp’s was his

chief mate, John Hilliard, who became a victim of

dropsy in 1681. Sharp recorded in his journal the

death of another of his crew in January 1682.

William Stephens (Stevens) “was observed, after his

eating of three Manchaneel

Apples, at King Charles’ Harbour, to waste

away strangely, till at length he was become a

perfect skeleton.” (Downie, 218) “Next morning we

threw overboard our dead man and gave him two French

vollies and one English one.” (Gosse, 218)

Captain John Halsey

succumbed from a tropical fever in 1716. One of

those present at the burial described his funeral:

With

great solemnity, the prayers of the Church of

England being read over him and his sword and

pistols laid on his coffin, which was covered

with a ship’s Jack. As many minute guns were

fired as he was old – viz, forty-six – and three

English vollies and one French volley of small

arms. His grave was made in a garden of

watermelons and fenced in to prevent his being

rooted up by wild pigs. (Gosse, 150)

Perhaps the more famous

of the pirates who died from disease was Mary Read,

who sailed with John

“Calico Jack” Rackham. Although she was

convicted of piracy, she was given a stay of

execution because she was pregnant. While in jail,

she “was seiz’d with a violent Fever, soon after

their Tryal, of which she died in Prison.” (Eastman,

40) According to Saint Catherine Parish Records, she

died on 28 April 1721, and was buried in the

Jamaican church’s cemetery.

Depending on the

circumstances, pirates might or might not take time

to honor their fallen comrades. If in the midst of

battle, bodies might be tossed over the side.

Otherwise they performed simple ceremonies as soon

as time permitted since pirates, like other seamen,

preferred not to have corpses on their ships.

Preserving bodies involved the use of alcohol, and

pirates weren’t likely to waste good spirits on the

dead.3 Prior

to burial the deceased was placed in his hammock

and, if possible, two round shots were placed within

as well – one at the head, the other at the feet to

weight the shroud so the remains would sink rather

than float to the surface. The hammocks were sewn

shut, with one stitch

through the deceased’s nose to insure that he

was dead. At the actual burial some comrades shared

memories of the dearly departed, then a prayer might

be spoken before the body slid off a plank into the

watery depths. For some, “the usual Ceremony of

firing the Guns” often followed. (Rediker, Between,

196) Unlike burials on land, the pirates displayed

little, if any, emotion. If the man had family, the

pirates might auction off the deceased’s belongings

and the money would be given to his survivors. In

1704, William Funnell described the result of one of

these sales: Depending on the

circumstances, pirates might or might not take time

to honor their fallen comrades. If in the midst of

battle, bodies might be tossed over the side.

Otherwise they performed simple ceremonies as soon

as time permitted since pirates, like other seamen,

preferred not to have corpses on their ships.

Preserving bodies involved the use of alcohol, and

pirates weren’t likely to waste good spirits on the

dead.3 Prior

to burial the deceased was placed in his hammock

and, if possible, two round shots were placed within

as well – one at the head, the other at the feet to

weight the shroud so the remains would sink rather

than float to the surface. The hammocks were sewn

shut, with one stitch

through the deceased’s nose to insure that he

was dead. At the actual burial some comrades shared

memories of the dearly departed, then a prayer might

be spoken before the body slid off a plank into the

watery depths. For some, “the usual Ceremony of

firing the Guns” often followed. (Rediker, Between,

196) Unlike burials on land, the pirates displayed

little, if any, emotion. If the man had family, the

pirates might auction off the deceased’s belongings

and the money would be given to his survivors. In

1704, William Funnell described the result of one of

these sales:

One of

our Men being dead, his things were sold as

follows. A chest, value five Shillings, was sold

for three Pounds; a pair of shooes, value four

Shillings and six pence, sold for thirty one

Shillings; half a pound of Thread, value two

Shillings, sold for seventeen Shillings and six

pence. (Rediker, Between, 197)

On 15 April 1709, Woodes

Rogers and his men encountered a Spanish ship,

which chose to fight rather than surrender. He noted

the attack and the aftermath in his journal:

Our

People were constrain’d to fall astern twice,

after the loss of one Man kill’d and three

wounded. The Boats and Sails were much damag’d

by the Enemies Partridge-shot, yet they again

attempted to come up and board her. At this

Attack my unfortunate Brother was shot thro the

Head, and instantly died, to my unspeakable

Sorrow . . . .

The next day, he buried

John. “About twelve we read the Prayers for the

Dead, and threw my dear Brother over-board, with one

of our Sailors, another lying dangerously ill. We

hoisted our Colours but half-mast up: We began

first, and the rest follow’d, firing each some

Volleys of small Arms. All our Officers express’d a

great Concern for the Loss of my Brother, he being a

very hopeful active young Man, a little above twenty

Years of Age.” (Rogers, 89-90)

After the death of his brother,

Captain Thomas Phillips “commit[ted] his body to

the deep” while praying. Drums and trumpets

provided appropriate music, while the traditional

volley of guns was fired. In this case, sixteen

muskets representing each year the man had lived.

(Little, Sea, 205).

Despite such rituals, pirates didn’t fear death or

hold it in high regard. As Ned Ward explained, “No

Man can have a Greater contempt for Death. For every

day he constantly shits upon his own Grave, and

dreads a Storm no more, than He does a broken Head,

when drunk.” (Rediker, Between, 250)

While pirates worked under a banner

of democracy,

there were times when they realized some actions

needed consequences so others wouldn’t follow suit.

(Much like society which sometimes hung the corpses

of pirates in gibbets

at key places where respectable seamen would see

what awaited them should they be foolish enough to

go on the account.) This was why breaking certain

rules earned dire punishments in their codes of

conduct. Bartholomew Roberts spelled out two

specific violations. While pirates worked under a banner

of democracy,

there were times when they realized some actions

needed consequences so others wouldn’t follow suit.

(Much like society which sometimes hung the corpses

of pirates in gibbets

at key places where respectable seamen would see

what awaited them should they be foolish enough to

go on the account.) This was why breaking certain

rules earned dire punishments in their codes of

conduct. Bartholomew Roberts spelled out two

specific violations.

VI. No

Boy or Woman to be allowed amongst them. If any

Man were found seducing any of the latter Sex,

and carry’d her to Sea, disguised, he was to

suffer Death.

VII. To Desert

the Ship, or their Quarters in Battle, was

punished with Death or Marooning. (Defoe,

212)

Three of John

Phillips’ articles spelled out death, although

they were more specific in detail.

2. If

any Man shall offer to run away, or keep any

Secret from the Company, he shall be maroon’d,

with one Bottle of Powder, one Bottle of Water,

one small Arm and Shot.

3. If any Man

shall steal any Thing in the Company, or game to

the Value of a Piece of Eight, he shall be

maroon’d or shot.

9. If at any

Time we meet with a prudent Woman, that Man that

offers to meddle with her, without her Consent,

shall suffer present Death. (Defoe, 342-343)

Those who suffered marooning

had two or three choices, depending on the islet

upon which they were abandoned. If the spot of land

was visible only at low tide, he might drown when

the tide came in. Or he might die after suffering

the agonizing pains of an empty belly and a parched

throat, even though he was surrounded by water.

There was always a slim chance he might survive, but

the odds were against him. If neither of these

alternatives appealed, he might shoot himself.

Some Asian pirates also adhered to a set of rules

that included death as a punishment:

When

captive women are brought on board, no one may

debauch them; but their native places shall be

ascertained and recorded, and a separate

apartment assigned to them in the ship; any

person secretly or violently approaching them

shall suffer death. (Antony, 114)

Whether such punishments

were actually meted out was another thing entirely.

Survival on a ship necessitated teamwork, so pirates

instituted and strictly adhered to another rule when

tempers grew short. If an argument devolved into a

fight, the quartermaster broke it up with the

reminder that as soon as they went ashore, the fight

would be resolved via a duel. Normally, the victor

was decided by first blood spilt, which didn’t

necessarily mean one man died. Such was not the case

when an argument ensued aboard Calico Jack’s boat

between two men, one of whom was the man Mary Read

loved.

It

happened this young Fellow had a Quarrel with

one of the Pyrates, and their Ship then lying at

an Anchor, near one of the Islands, they had

appointed to go ashore and fight, according to

the Custom of the Pyrates: Mary Read was

to the last Degree uneasy and anxious, for the

Fate of her Lover; she would not have had him

refuse the Challenge, because, she could not

bear the Thoughts of his being branded with

Cowardice; on the other Side, she dreaded the

Event, and apprehended the Fellow might be too

hard for him . . . in this Dilemma, she shew’d,

that she fear’d more for his Life than she did

for her own; for she took a Resolution of

quarrelling with this Fellow her self, and

having challenged him ashore, she appointed the

Time two Hours sooner than that when he was to

meet her Lover, where she fought him at Sword

and Pistol, and killed him upon the Spot.

(Defoe, 158)

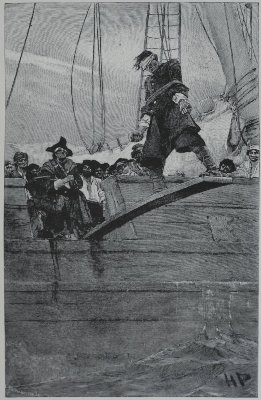

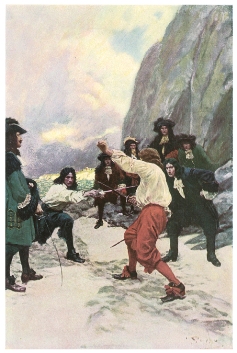

Who Shall Be Captain? by Howard

Pyle, 1911

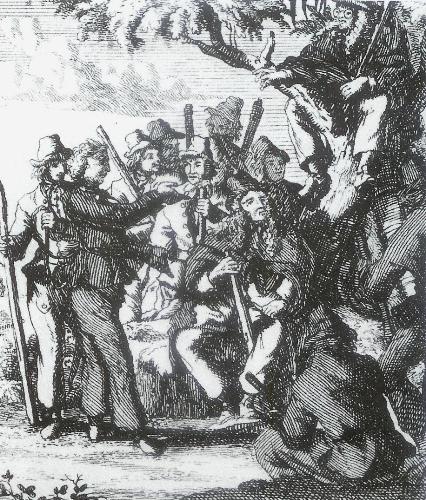

Mary Read Kills Her

Antagonist, 1837

Being Come to the Place of Duel, the

Englishman Stabbed the Frenchman in the Back by

Geroge Albert Williams, 1914

(Sources: Wikimedia

Commons, Charles

Ellms's The

Pirates Own Book, Dover's Pirates)

The

boatswain of another crew was disrespectful to

Captain John Evans and an argument ensued. Evans

insisted on satisfaction ashore, but his opponent

refused so Evans gave him a “hearty drubbing.” In

retaliation, the boatswain shot Evans in the head,

and then jumped overboard. Some of his mates pursued

the boatswain and dragged him back aboard the ship

to stand trial. The whole incident had taken so much

time that a gunner didn’t wish to waste any

additional time on the matter and, opting to deliver

justice himself, shot the boatswain.

Henry

Morgan also killed one of his men. A Frenchman

had challenged a buccaneer to a duel, but rather

than heed the traditional rules, the man stabbed the

Frenchmen with a sword while his back was turned.

Morgan rewarded such cowardice with hanging.

The very nature of their work meant pirates might

fall during battle, but they might not be killed

directly. Death could be a consequence of exploding

gunpowder, flying splinters, falling masts and

tackle, or overturning guns. While ship-to-ship and

hand-to-hand combat might kill a pirate, so could

just the act of boarding the prey when the two ships

were grappled together. A shipmaster, who sailed

with the French corsair René

Duguay-Trouin, was crushed after he fell

between the vessels. Captain Peter Harris, who

sailed with Bartholomew Sharpe, sustained wounds in

both legs as he tried to board a Spanish ship off

Panama in 1680.

But many pirates were killed from wounds sustained

in the fight. Bartholomew Roberts, for example, died

when grapeshot struck him in the throat after HMS

Swallow attacked his ships off the coast of

Africa in 1722.

He

settled himself on the tackles of a gun, which

one Stephenson, from the helm, observing, ran to

his assistance, and not perceiving him wounded,

swore at him, and bid him stand up, and fight

like a man; but when he found his mistake, and

that his captain was certainly dead, he gushed

into tears, and wished the next shot might be

his lot. They presently threw him overboard,

with his arms and ornaments on, according to the

repeated request he made in his lifetime . . .

(Pirate’s, 145)

Nineteen of Roberts’s men, who were captured and

taken to Cape Coast

Castle, died either from their wounds or

diseases before they could be tried. One of those

men was Roger Ball, who, when asked how he came to

be badly burned, said, “Why John Morris fired a

pistol into the powder, and if he had not done it, I

would [have].” (Gosse, 44) Morris succeeded in

killing himself, but the attempt to blow up the ship

failed; yet Morris and Ball weren’t the only pirates

who would rather kill themselves than be captured.

What Morris attempted to do was what one pirate had

told the master of Samuel, captured in

August 1720, that they would do.

If we

are captured, we will set fire to the powder

with a pistol, and all go merrily to hell

together. (Botting, 165)

Other pirates of the

golden age also averred to perpetrate their own

demise rather than be captured. That sometimes meant

blowing up the ship, but other times it involved

killing each other. One example of the latter

involved two pirates who ritualized the vow:

[They]

took their Pistols, and laid them down by them,

and solemnly swore to each other, and pledg’d

the Oath in a Bumper of Liquor, that if they saw

that there was at last no possibility of

Escaping, but that they should be taken, they

would set Foot to Foot, and Shoot one another,

to Escape Justice and the Halter. (Rediker,

Villains, 149)

Captain Charles Harris

and his men preferred to “always [keep] a Barrel of

Powder ready to blow up the Sloop rather than be

taken.” (Rediker, Villains, 149) When they

encountered HMS Greyhound in 1723, one man

tried to ignite the keg, but “being hindered, he

went forward, and with his Pistol shot out his own

Brains.” (Rediker, Villains, 151) Joseph

Cooper’s crew, however, succeeded. When naval

officers attempted to board the ship, the pirates

blew themselves up.

Caesar,

who sailed with Edward

Thache (Blackbeard),

had tried to ignite the powder magazine on their

ship during Lieutenant Robert

Maynard’s surprise attack at Ocracoke Inlet

four years earlier. Two prisoners intervened, and

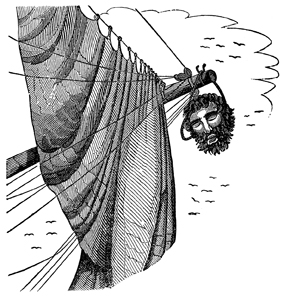

Caesar was taken into custody. Maynard’s account of

the fight simply reported:

I had

eight Men killed and 18 wounded. We kill’d 12,

besides Blackbeard, who fell with five Shot in

him, and twenty dismal Cuts in several Parts of

his Body. I took nine prisoners, mostly Negroes,

all wounded. (Cordingly, 176)

The

Boston News-Letter provided a more lurid

description of their fight three months later.

. . .

Maynard making a thrust, the point of his Sword

went against Teach’s Cartridge Box, and bended

it to the Hilt, Teach broke the Guard of it, and

wounded Maynard’s Fingers but did not disable

him. where upon he Jumpt back, threw away his

Sword and fired his Pistol, which wounded Teach.

Demelt struck in between them with his Sword and

cut Teach’s Face pretty much . . . one of

Maynard’s Men being a Highlander, ingaged Teach

with his broad Sword, who gave Teach a cut on

the Neck, Teach saying well done Lad, the

Highlander reply’d, if it be not well done, I’ll

do it better, with that he gave him a second

stroke, which cut off his Head, laying it flat

on his Shoulder, Teach’s Men being about 20, and

three or four Blacks, were all killed in the

ingagement . . . (British, I:295)

In all, Thache sustained twenty-five wounds. Maynard

had his corpse dumped over the side of the ship,

while he ordered the head hung from Jane’s

bowsprit.

Aruj

Barbarossa fell during a siege of Tlemcen in

1518. Forty-seven years later another Barbary

corsair died while attacking Malta. Turgut Reis

died doing what he enjoyed best – fighting

Christians. The English pirate Captain Parker was

killed in action against Dutch pirates at Marmora in

1611. Six years later, Basil Ringrose died when the

Spanish launched a surprise attack on the pirates in

Mexico. Fifty-four were killed in all and, according

to William

Dampier, their bodies were “stript, and so cut

and mangl’d, that he scarce knew one man.”4

(Preston, 132) In the middle of the 1700s, Captain William

Death engaged a French privateer. During the

battle, which lasted three hours, Death was killed.

Even retirement didn’t guarantee a peaceful life. Thomas Tew,

who lived in Rhode

Island, had made his fortune, but his men kept

trying to convince him to make one last voyage. It

took several years, but they finally succeeded in

1695.

They

prepared a small Sloop, and made the best of

their Way to the Straits, entering the Red

Sea, where they met with and attack’d a Ship

belonging to the Great Mogul; in the Engagement,

A Shot carry’d away the Rim of Tew’s

Belly, who held his Bowels with his Hands some

small Space; when he dropp’d, it struck such a

Terror in his Men, that they suffered themselves

to be taken without making Resistance.

(Defoe, 439)

Jean

Laffite (left) and Thomas Tew

with the governor by Howard Pyle, 1894 (right)

Sources: (unknown, Dover's Pirates)

Like many who received pardons for past crimes, Jean

Laffite resumed his pirating ways while

residing on Galveston

Island after the Battle of

New Orleans. In 1820, the United States Navy

drove him from that haven. Three years later, news

reports in various papers declared he had died

battling two Spanish warships. Jeff Modzelewski’s

translation of an article that originally appeared

in the Sunday, 20 April 1823, issue of Gaceta de

Columbia read:

The

Columbian corsair General Santander, of 43 tons,

at the command of Captain Jean Laffite, gave

chase at 5 in the morning on February 4, at 20

leagues beyond the Omoa tradewinds, opposite

Triumph of the Cross, to a brigantine and a

Spanish schooner, until 10 at night: the

brigantine, after an hour of combat, and at the

point of surrendering, signaled with lanterns to

the schooner, which immediately turned upon the

corsair: at this time Captain Laffite, mortally

wounded, stimulated the ardor of his crew and

turned over the command of the ship to his

second in command, who suffered the same fate.

Contramaestre [Chief petty officer or boatswain]

Francisco Similien, after the death of the

second in command, continued sustaining the

combat until one at night when, it being

impossible to continue it, changed course, as

did the two Spanish vessels, which doubtless

were very damaged by the fire of the corsair,

since they did not pursue its retreat: Captain

Laffite died from his injuries the next day . .

. .5

In the early eighteenth

century, pirates adopted common symbols denoting

death and placed them on their flags.

Skulls and crossed bones were frequently included on

gravestones in the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries. Paintings of the period also included

allegorical symbols of death. To the pirates,

dancing skeletons were akin to the fate that awaited

them should they be caught (dancing the hempen jig).

Raised glasses denoted a toast to death, while

weapons warned that death awaited those who dared to

resist. Sandglasses and wings indicated how quickly

time passed. Regardless of the symbols decorating

their jacks, the pirates warned one and all that

death was a real possibility. Even before such flags

flew from ship masts, murder was part of this

criminal way of life.

Depictions

of Jolly Rogers displaying symbols connected to

death

Like other buccaneers of the seventeenth century,

the French flibustier Captain Daniel could

be particularly bloodthirsty when fighting enemies,

but he was also a pious man. While anchored off

Isles des Saintes, he asked a priest to celebrate

mass aboard his ship. The piety of one of his men

was less than expected, so Daniel shot him in the

head. Then Daniel told the priest, “Do not be

troubled, my father, he is a rascal lacking in his

duty and I have punished him to teach him better.”

(Gosse, 103) After mass ended, the flibustiers dumped

the body overboard.

Captain

Kidd also killed one of his own men, even

though that might not have been his intent; murder

would become one of the charges lodged against him

when he stood trial in 1701. The dispute arose

because Kidd refused to attack a Dutch ship.

Moor,

the gunner, being one day upon deck, and talking

with Kidd . . . some words rose betwixt them,

and Moor told Kidd, that he had ruined them all;

upon which, Kidd, calling him dog, took up a

bucket and struck him with it, which breaking

his skull, he died the next day. (Pirate’s,

62)

It was a ship’s crew and

passengers, as well as residents of towns, who paid

the ultimate sacrifice when pirates attacked. After

Edward

England assaulted the British

East India Company’s Cassandra

in July 1720, Captain James McRae

left this account.

. . .

many of my men were killed or wounded, and no

hopes left of us from being all murdered by

enraged barbarous Conquerors, I order’d all that

could, to get into the longboat under the cover

of the smoke of our guns, so that with what some

did in boats, & others by swimming, most of

us that were able reached ashoar by 7 o’clock.

When the Pyrates came aboard, they cut three of

our wounded men to pieces. I, with a few of my

people, made what haste I could to the

Kingstown, 25 miles from us, where I arrived

next day, almost dead with fatigue and loss of

blood, having been sorely wounded in the Head by

a musket ball. (Konstam, Scourge,

144)

Edward

“Ned” Low was a brute when it came to his

victims. Sometime after he parted company with George

Lowther in 1722, Low fell in with a French

warship. He and his pirates “took all the crew out

of her, but the cook, who, they said, being a greasy

fellow would fry well in the fire; so the poor man

was bound to the main-mast, and burnt in the ship,

to the now small diversion of Low and his

mermidons.” (Pirate’s, 159) Edward

“Ned” Low was a brute when it came to his

victims. Sometime after he parted company with George

Lowther in 1722, Low fell in with a French

warship. He and his pirates “took all the crew out

of her, but the cook, who, they said, being a greasy

fellow would fry well in the fire; so the poor man

was bound to the main-mast, and burnt in the ship,

to the now small diversion of Low and his

mermidons.” (Pirate’s, 159)

Nor were western pirates the only ones who

slaughtered people. Pirates who prowled the waters

of South China often murdered some crew members on

the vessels they seized so the remainder would

submit to their demands. Others slew entire crews to

prevent them from talking. In April 1809, Guo

Lianghuo seized a boat off the Xiangshan coast. He

and his men garnered 550 taels of silver and stole

the cargo before trussing up their victims and

throwing them overboard. One of Xie Yaer’s captives

had the audacity to curse the pirate chief, who

smote the man into pieces and then fed these to the

fish. When Chen Lassan encountered similar defiance,

his men sliced the prisoner in half twice, severed

his limbs, and removed his heart and liver, which

the pirates soaked in wine and then ate.

Nor were men the only victims

who refused to submit. In 1809, pirates attacked the

village of Kan-shih in Guangdong, China.

Mei

ying, the wife of Ke choo yang was very

beautiful, and a pirate being about to seize her

by the head, she abused him exceedingly. The

pirate bound her to the yard-arm; but on abusing

him yet more, the pirate dragged her down and

broke two of her teeth, which filled her mouth

and jaws with blood. The pirate sprang up again

to bind her. Ying allowed him to approach but as

soon as he came near her, she laid hold of his

garments with her bleeding mouth and threw both

him and herself into the river where they were

drowned. (Bandits, 274)

A seaman for the British

East India Company, Richard

Glasspoole also found himself a prisoner of

ladrones (Chinese pirates) in September 1809. He

spent more than a month in captivity while waiting

for his ransom to be paid. After his release, he

published an account of his experiences:

The

ladrones were paid by their chief ten dollars

for every Chinamen’s head they produced. One of

my men, turning the corner of a street, was met

by a ladrone running furiously after a Chinese.

He had a drawn sword in his hand and two

Chinamen’s heads which he had cut off, tied by

their tails and slung round his neck. I was

witness myself to some of them producing five or

six to obtain payment!!! (Captured,

312)

Three years earlier, John Turner, another

Englishman, became a “guest” of Chinese pirates for

nearly six months. He witnessed an attack on an

Imperial Navy vessel and described the brutality

meted out to two officers. “One man had his feet

nailed to the deck and was beaten with rattan whips

until he vomited blood, ‘and after remaining some

time in this state, he was taken ashore and cut to

pieces.’ The other officer ‘was fixed upright, his

bowel cut open, and his heart taken out’.” Like Chen

Lassan’s victim, the pirates dined on that man’s

heart. (Antony, 116) Such acts of cannibalism had a

three-fold purpose. First, they demonstrated to the

Imperial Navy just how far the pirates were willing

to go when seeking revenge against anyone who stood

in their way. Second, dining on the hearts and

livers of their victims transferred the courage and

longevity of the slain to the pirates. Lastly,

participating in the act solidified the ties that

bound the pirates into a cohesive group whose power

and cruelty terrified other potential victims.6

Nor were attacks on warships any less gruesome four

decades later when Shap ’ng

Tsai prowled the waters off Guangdong and

Fujian, China.

[F]ive

war junks . . . were chased by six pirate boats,

which boarded them, put their crews to death,

and carried the commanders . . . on shore, where

a fire was kindled, and the unfortunate officers

were burnt alive. (Vallar, 39)

Even today, death

remains a threat to seamen who encounter pirates. In

December 1992, Baltimar

Zephyr was attacked in the Malacca

Strait. The captain and first mate were both

murdered. According to a news report, “A crewman

said that he and Mr. Pereja [the first mate] were

threatened by a man armed with a rifle and a pistol.

The pirates shot up the radar before taking Mr.

Pereja below, where [he] was shot dead in the

captain’s cabin. It is believed that Captain

Bashforth tried to barricade himself in a lavatory

before suffering the same fate.” (Bennett) Six years

later, Cheung

Son and twenty-three seamen disappeared.

Six crew members’ bodies eventually surfaced off

Shantou, China; they had been bound, gagged, and

wrapped in fishing nets that were weighted down. On

13 January 1999, Chinese authorities arrested the

pirates. Photographs were discovered showing them

celebrating the hijacking of and murders on Cheung

Son.

During the seventeenth century, some buccaneers were

particularly sadistic, especially when it came to

their treatment of Spaniards. Daniel

Montbars, whom some nicknamed “The

Exterminator,” liked to “cut open the stomach of his

victim, extract one end of his guts, nail it to a

post and then force the wretched man to dance to his

death by beating his backside with a burning log.”

(Cordingly, Under, 132) Gerrit Gerritszoon,

better known as Rock

Brasiliano, “perpetrated the greatest

atrocities possible against the Spaniards. Some of

them he tied or spitted on wooden stakes and roasted

them alive between two fires, like killing a pig –

and all because they refused to show him the road to

the hog-yards he wanted to plunder.” (Exquemelin,

80) Even worse was Jean David Nau (François

L’Olonnais). Headed toward San Pedro, he came

across Spanish soldiers waiting to ambush him;

instead he captured them.

Being

possessed of a devil’s fury, [he] ripped open

one of the prisoners with his cutlass, tore the

living heart out of his body, gnawed at it, and

then hurled it in the face of one of the others,

saying “Show me another way, or I will do the

same to you.” (Exquemelin, 107)

The French buccaneer Raveneau de Lussan recorded in

his journal

one incident where the ransom for his captives never

arrived. “We were forced to apply to our prisoners

the customary rigorous measures used to intimidate

our enemies – to have them throw dice to see which

men would lose their heads.” (Earle, 106) A few

months before his capture in 1714, Alexander Dalzel

and seven other pirates stole a French vessel while

in Le Havre. They “murdered the pylot with a dagger,

and tooke the master’s brother and tyed his hands

and legs and cast him off at sea.” (Earle, 66)

While

walking the plank was more fiction than reality,

there were a few instances where pirates employed

this technique to end their victims’ lives; none of

these occurred before the nineteenth century. The Niles

Weekly Register for 5 October 1822,

included an item that had originally appeared in the

Kingston Chronicle several months earlier. It

involved an attack on Blessing, a sloop out

of Jamaica. The pirate leader ordered a plank While

walking the plank was more fiction than reality,

there were a few instances where pirates employed

this technique to end their victims’ lives; none of

these occurred before the nineteenth century. The Niles

Weekly Register for 5 October 1822,

included an item that had originally appeared in the

Kingston Chronicle several months earlier. It

involved an attack on Blessing, a sloop out

of Jamaica. The pirate leader ordered a plank

. . .

run out in the starboard side of the schooner,

upon which he made captain Smith walk, and that,

as he approached to the end, they tilted the

plank, when he dropped into the sea, and there,

when in the effort of swimming, the captain

called for his musket, and fired at him

therewith, when he sank, and was seen no more!

(Pirate’s, 161)

An incident seven years

later involved pirates who captured a Dutch brig off

the coast of Cuba. After binding each man’s arms

together and blindfolding him, the pirates chained

round shot to the seamen’s feet. Then the pirates

forced them to walk off the ship into the sea.

Conversely, the victims of pirates sometimes struck

a blow against their attackers. When Howell

Davis visited Principe Island in the Gulf of

Guinea, he told the Portuguese governor he was a

pirate hunter. Rather than being duped, the governor

invited Davis to visit him for drinks. As the ten

pirates climbed the hill to the fort, the narrow

path forced them to walk single file. When they

reached a specific point, the soldiers who had lain

in wait for the pirates rose up and fired their

muskets. Howell sustained four wounds, one to his

stomach, but managed to stagger forward until

another bullet hit him. Before he died, he fired his

pistols at the Portuguese. William Snelgrave, a

captured merchant captain aboard the pirates’ ship,

ended his description of the event with “The

Portuguese, being amazed at his great strength and

courage, cut his throat that they might be sure of

him.” (Sanders, 53) Also killed in the attack were

the ship’s surgeon and two others.

L’Olonnais suffered a fitting death after all the

tortures he inflicted on victims. His last

expedition in 1668 was beset with bad luck. At the

mouth of the Nicaragua River:

He was

set upon both by the Indians and the Spaniards:

many of his men were killed and l’Olonnais and

the rest were forced to flee. L’Olonnais

determined not to return to his comrades on the

island without a ship. He held council with the

men still in his company and they resolved to

take the longboat along the coast of Cartagena

in an attempt to capture some vessel or other.

But now it

seems God would permit this man no further

wicked deeds, but was ready to punish him for

all the cruelties he had inflicted on so many

innocent people by a cruel death. On arrival in

the Gulf of Darien, he and his men fell into the

hands of those savages the Spaniards called

Indios Bravos. According to one of his

companions, who only saved himself from a like

fate by running away, l’Olonnais was hacked to

pieces and roasted limb by limb.

(Exquemelin, 117)

Death, of course, was

the usual punishment meted out to pirates who were

captured. They knew this, which may be why they

tended to “laugh in the face of death.” Bartholomew

Roberts and his men liked to raise this toast: "Damnation to him who ever

lived to wear a halter." (Rediker, Villains, 150)

To

further show their disregard for justice and the

death sentence, pirates often held mock trials where

they would prosecute each other on charges of

piracy. One man played the judge, another the

prosecutor. Others served on the jury or adopted

less officious roles, such as a scribe, sheriff, or

witness. Of course, someone had to be the accused.

Like putting on a play, they donned makeshift

costumes that ridiculed the pomp and circumstance of

a real trial. To

further show their disregard for justice and the

death sentence, pirates often held mock trials where

they would prosecute each other on charges of

piracy. One man played the judge, another the

prosecutor. Others served on the jury or adopted

less officious roles, such as a scribe, sheriff, or

witness. Of course, someone had to be the accused.

Like putting on a play, they donned makeshift

costumes that ridiculed the pomp and circumstance of

a real trial.

Lacking a black robe, the judge “had a dirty

Tarpulin hung over his Shoulders.” Lacking a wig,

he stuck a thrum cap on his head. He put “a large

Pair of Spectacles on his Nose” and took his

exalted place up in a tree so as to look down on

the proceedings from a position above it all.

Scurrying around below were “an abundance of

Officers attending him,” comically using ship’s

tools, “Crows, Handspikes, &c. instead of

Wands, Tipstaves, and such like.” Soon “the

Criminals were brought out,” probably in chains,”

making a thousand sour Faces” as they entered the

outdoor courtroom. The attorney general “opened

the Charges against them.” (Rediker, Villains,

156-157)7

This parody scoffed at death and, by switching which

roles each pirate played from one day to the next,

they confused the proper order of society. Yet such

disdain also portended the future for some enemies

of all mankind.8

At one mock trial that Thomas

Anstis’s crew held on a cay off Cuba, George

Bradley, who played the judge, intoned the following

sentence on the prisoner:9

Then

heark’ee, you Raskal at the Bar; hear me,

Sirrah, hear me. – You must suffer for three

Reasons: First, because it is not fit I should

sit here as Judge, and no Body be hang’d. –

Secondly, you must be hang’d, because you have a

damn’d hanging Look: – And thirdly, you must be

hang’d, because I am hungry; for know, Sirrah,

that ’tis a Custom, that whenever the Judge’s

Dinner is ready before the Tryal is over, the

Prisoner is to be hang’d of Course. – There’s

Law for you, ye Dog. – So take him away Gaolor.

(Defoe, 293-294)

Captain Herdman, who

presided over the Vice-Admiralty Court passing

judgment on the pirates from Bartholomew Roberts’

ships, delivered a far different soliloquy in 1722.

Ye and

each of you are adjudged and sentenced to be

carried back to the place from whence you came,

from thence to the place of execution without

the gates of this castle, and there within the

flood marks to be hanged by the neck till you

are dead, dead, dead. And the Lord have mercy on

your souls. (Pirates, 7)

It took just three weeks

to try and execute those pirates sentenced to death.

One hundred sixty stood trial at Cape Coast

Castle that year. Twenty were sentenced to

seven years of hard labor in the Cape Coast mines,

and seventeen were sent to London to serve their

prison sentences in the Marshalsea

Prison. In an ironic twist of fate, some of

Bartholomew Roberts’s men once told the captured

Samuel’s master, “We shall accept no Act of Grace,

may the King and Parliament be damned with their act

of Grace for us, neither will we go to Hope Point

[Execution Dock] to be hanged a-sun-drying.”

(Botting, 165) Yet fifty-two did dance the hempen

jig, just not at that particular place. Instead,

they swung on the ramparts of Cape Coast Castle, and

eighteen were left to dry in the sun on one of three

prominent hills overlooking the water.10

Death by execution was the usual consequence for

those pirates whom authorities eventually captured.

Marcus Rediker estimated that “[b]etween 1716 and

1726, no fewer than 418 were hanged, and in truth

the actual number was probably one-third to one-half

higher.” (Rediker, Villains, 163) Executions

were the norm as far back as history records, but

hanging wasn’t always the means by which a pirate

bade a final farewell.

After the ransom was paid that freed Julius

Caesar, he returned to the Cilician

pirates’ lair and crucified them in 75 BC. On 24

August 1217, Hugh de Burgh finally caught Eustace the

Monk and gave him two choices: his beheading

could take place at the center or at the side of the

ship. Klaus

Störtebeker and his Likedeeler were captured

in 1401 and taken to Hamburg, Germany.11 All

seventy-two pirates were beheaded in October.

Supposedly, the executioner and Störtebeker reached

an agreement whereby the executioner would lop off

Störtebeker’s head first. Then his corpse would

traverse the ground where his men were aligned in a

row. At the point where the headless pirate finally

toppled over, any men he had passed (eleven in all)

would be pardoned. In reality, all were decapitated

and their heads crowned spikes along the waterfront.

Hamburg officials also executed another thirty-three

pirates, as well as their leader Klein

Henszlein, in 1573. Beheading was often the

punishment meted out to pirates in China and other

Asian countries, even as late as 1891 when the Namoa

pirates were put to death in Hong Kong.

Beheading of Eustace the Monk during

the Battle off Sandwich in 1217 by Matthew

Paris, 13th century

Beheading of Klaus

Störtebeker and his men

Execution of the Namoa Pirates on 11 May

1891 at Kowloon City, China

(Sources: Wikimedia

Commons, Pirate

Images, New

York Public Library)

Spain and her American colonies preferred to garrote

a pirate, strangling him with a rope that was

twisted either by hand or with the use of a cudgel

or stick. For example, after buccaneers raided

Tampico in the spring of 1684, three Spanish ships

pursued the pirates. They captured 104, whom they

took to Veracruz. Eleven were garroted, but one was

saved after the cord being twisted around his neck

broke not once, but twice. At this point a priest

intervened, saying, “This man has offered himself to

the Virgin, and God does not wish that he die.”

(Little, Buccaneer’s, 208)

Nor were such executions simple affairs, for the

Spanish imposed a ritualistic element to the

punishment. The night before a priest and pirate

would pray for the latter’s salvation until it was

nearly dawn. He was then expected to confess his

guilt before being conducted to the place of

execution where he was made to sit or he was tied to

a pole. After slipping a rope around his neck, the

executioner stood behind him and turned the cudgel

until the pirate died.

Hanging, however, was the most common form of

execution, especially in Britain

and her colonies. When Venetian galleys returned

home in the early 1600s, thirty-six English pirates

dangled from the yardarms. Before the golden age,

only a few pirates suffered the punishment of death,

and often these men were the ringleaders. That

changed as merchants became more powerful and

governments became less tolerant; authorities strove

to make the seas safer for merchants, travelers, and

seamen. “Between 1716 and 1726 . . . roughly one in

every ten pirates came to an end on the gallows . .

. .” (Rediker, Villains, 163) For example,

thirty-four pirates who followed Stede

Bonnet were hanged in 1718. Four years later,

Jamaica put Matteo Luque and forty-one of the

fifty-eight who followed him to death. In 1723,

twenty-five pirates were executed at Newport, Rhode

Island, six on Antigua, another twelve on Curaçao,

and two more in Bermuda. The previous year,

fifty-two men were hanged at Cape Coast

Castle. The governor of the castle, General

Phipps, said afterward:

We hope

the example that has been made of this gang will

be a means to affright and deter all others from

pursuing such vile practices on this coast and

that the trade thereby will be secured free and

undisturbed from the depredations of such

miscreants for some time to come. (Sanders,

238)12

After Calico Jack

Rackham captured the vessel on which Mary Read

served, Jack discussed the good life of a pirate, as

well as the “ignominious Death” Read might suffer if

caught and tried. She considered hanging “no great

Hardship.”

[W]ere

it not for that, every cowardly Fellow would

turn Pyrate, and so infest the Seas, that Men of

Courage must starve: – That if it was to the

Choice of the Pyrates, they would not have the

Punishment less than Death, the Fear of which

kept some dastardly Rogues honest; that many of

those who are now cheating the Widows and

Orphans, and oppressing their poor Neighbours,

who have no Money to obtain Justice, would then

rob at Sea, and the Ocean would be crowded with

Rogues, like the Land, and no Merchant would

venture out; so that the Trade, in a little

Time, would not be worth following. (Defoe,

158-159)

Hanging a pirate did not

just involve a guilty sentence and a rope around the

neck. To execute someone required rituals, which

unfolded once a pirate was condemned to die.

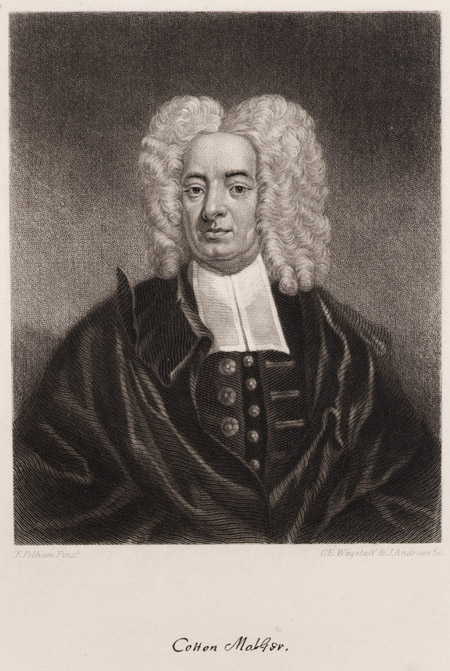

Ministers, such as Paul Lorrain and Cotton

Mather, talked with the prisoners in hopes of

getting them to confess and repent. Lorrain, the Ordinary at

Newgate, visited William

Kidd twice a day. While Surgeon Atkins tried

to get the pirates who had followed Bartholomew

Roberts to apologize for their wicked crimes, he was

told, “We are poor rogues and so must be hanged,

while others, no less guilty in another way,

escaped.” (Botting, 175) Hanging a pirate did not

just involve a guilty sentence and a rope around the

neck. To execute someone required rituals, which

unfolded once a pirate was condemned to die.

Ministers, such as Paul Lorrain and Cotton

Mather, talked with the prisoners in hopes of

getting them to confess and repent. Lorrain, the Ordinary at

Newgate, visited William

Kidd twice a day. While Surgeon Atkins tried

to get the pirates who had followed Bartholomew

Roberts to apologize for their wicked crimes, he was

told, “We are poor rogues and so must be hanged,

while others, no less guilty in another way,

escaped.” (Botting, 175)

On the Sunday before the scheduled hanging, the

minister preached an execution sermon with the

condemned present in the congregation. Finally, the

fateful day arrived, and how each pirate comported

himself varied from one man to another. Sometimes

providing false courage to a pirate was essential in

conveying the prisoner from jail to the site of his

execution. The procession to Wapping’s

Execution Dock, a distance of three miles,

took at least two hours.

. . .

yet the Courage that strong Liquors can give,

wears off, and the Way they have to go is

considerable, they are in Danger of recovering.

. . . For this reason they must drink as they

go; and the Cart stops for that Purpose three or

four, and sometimes half a dozen Times, or more,

before they come to their Journey’s End.

(Zacks, 388)

William Kidd was already

drunk when he left Newgate

Gaol in 1701, and even more so by the time he

arrived at Wapping.

Other times, the pirates required no such

sustenance. When Dennis Macarty arrived at his place

of execution, blue ribbons decorated his neck,

wrists, knees, and hat. He told the crowd, “Some of

my friends said I should die in my shoes. To make

’em liars, I kicks them off.” (Downie, 28) Then he

did just that. Thomas Morris’s ribbons were red. Charles

Gibbs “was dressed in a blue roundabout

jacket, and blue trowsers and white cap, the jacket

bearing on the left arm the figure of an anchor

worked with white ribbon . . . .” (Gibbs, 144) As

Christopher Sympson passed through the crowd of

people who gathered to witness the hangings at Cape

Coast Castle, he saw Elizabeth Trengrove, a former

captive, and declared, “I have lain with that bitch

three times and now she has come to see me hanged.”

(Botting, 175)

The first six of Roberts’s pirates to hang were the

most irascible and stubborn of his men. According to

Atkins:

They all

exclaimed against the severity of the court, and

were so hardened as to curse, and wish the same

justice might overtake all the members of it, as

had been dealt to them . . . . [They walked] to

the gallows without a tear . . . showing as much

concern as a man would express at travelling a

bad road. (Sanders, 239)

Pirates never ascended

the gallows alone; they were accompanied by men of

the cloth and the executioner, who placed the noose

around each pirate’s neck. In exchange for executing

Kidd, the hangman received £1 for each pirate hanged

that day and one shilling six pence for each noose

he provided.

The sheriff or marshal read aloud the execution

order. It was expected the condemned would confess

to the wrong path he had taken, tell the gathered

crowd he deserved to be hanged, and then seek God’s

forgiveness for his sins. He might also impart a

final message or words of wisdom at this juncture. Walter

Kennedy followed the “script” in uttering his

final words on 19 July 1721:13

I am

brought to this Place of Shame and Disgrace for

Crimes which fully deserve so vile a death, and

I freely confess my self guilty of the Crimes I

was convicted of, as well as many other Faults

of the like Nature, for which I beg the Pardon

of God, and of you my Countrymen . . . (Pirate’s,

127)

John Augur, who hadn’t

shaved or taken a bath at least since his capture

and was clad in tattered clothes, showed only

remorse when he drank a glass of wine and wished

Governor Woodes

Rogers much success in curbing piracy.

Others failed to adhere to “scripted” expectations.

Thomas Morris grinned and declared that his only

wish was that he could have been a greater plague

than he had been. Captain Richard Thomas declared:

“Yes, I repent that I had not done more mischief,

and that we did not cut the throats of them that

took us, and I’m extremely sorry that you ain’t

hanged as well.” (Downie, 28)

Some straddled both sides, first repenting and then

changing their minds. According to a pamphlet

published after John

Quelch’s death, “[t]he last Words he spake to

One of the Ministers at his going up the Stage, were

I am not afraid of Death, I am not afraid of the

Gallows, but I am afraid of what follows; I am

afraid of a Great God, and a Judgment to come.” But

a short time later, his attitude changed.

“Gentlemen, ’Tis but little I have to speak: What I

have to say is, I desire to be informed for what I

am here, I am condemned only upon Circumstances. I

forgive all the World: So the Lord be Merciful to my

Soul.” The minister admonished the crowd not to pay

heed to Quelch’s words, to which he responded: “They

should also take care how they brought Money into

New-England, to be Hanged for it!” (Pirate’s,

67-68)

Once the noose was tightened, the minister prayed. After

the hangman fitted a noose around Kidd’s neck,

Paul Lorrain sang a psalm. One example was Psalm 51,

often referred to as the “Miserere.” The first two

verses of which are:

Have

mercy on me, O God, according to thy steadfast

love;

According to

thy abundant mercy blot out my transgressions.

Wash me

thoroughly from my iniquity, and cleanse me from

my sin! (The Holy Bible, Revised

Standard Edition)

Gallows of the period

differed from the scaffold with a trap door that we

commonly associate with a hanging. In Kidd’s day,

two poles supported a wooden beam and a raised

platform. Steps or a ladder provided access to the

platform, while the rope dangled from the horizontal

beam. The plank would be yanked away and the men

would drop. Alternative options were to have the

condemned stand in a cart or on a barrel or ladder.

The cart would be driven out from under the person,

or the prisoner was turned or pushed off the

pedestal.

Following a final prayer, the hangman did his job.

Someone gave Stede Bonnet a farewell nosegay, which

he still clutched after the cart he stood upon

rolled away and he dropped at White Point

in Charleston, South Carolina in December

1718. Kidd was turned off and dangled in the

air, but the rope snapped and he dropped into the

mud. Once again, the executioner bundled him up a

ladder, fitted another noose around his neck, and

then pulled the ladder away. Kidd did not escape

death a second time.

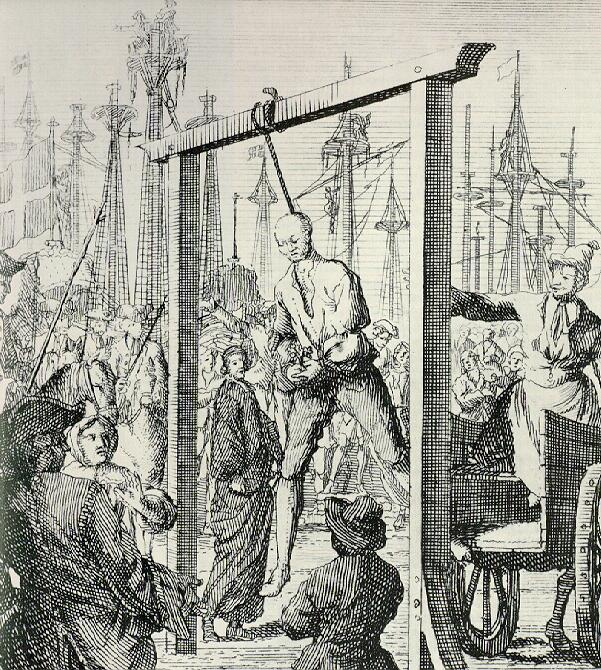

Hanging of a buccaneer

at Execution Dock by unknown artist of the

17th century

Execution of Major Stede

Bonnet from the 1725 Dutch version of Captain

Charles Johnson's A General History of the

Pyrates

(Sources: Wikimedia

Commons, Pirate

Images)

In October 1821, Charles

Gibbs, whose real name was James D. Jeffers,

found himself a prisoner of the United States Navy.

Before his capture, he had hacked off the limbs of

the captain of one captured ship. Another one was

torched with her entire crew still alive and on

board. After an untimely escape, Gibbs eventually

danced the hempen jig on 22 April 1831, a decade

after he was first caught. So many came to Ellis

Island to watch the execution that some had to

remain in their boats, one of which capsized and a

man drowned. Gibbs calmly walked to the west side of

the island, betraying “no marks of terror, although

it was evident that he shrunk from death. When first

brought out, he surveyed the gallows with an anxious

eye, but seemed satisfied that there was no avoiding

his fate.” (Gibbs, 145) When he was ready, he let go

of his handkerchief, and the hangman chopped the

cord that held two fifty-six-pound weights, which

violently snatched the condemned prisoner from the

scaffold. After he was pronounced dead, his body was

delivered “to Doctor John Augustine Smith, Professor

of Anatomy, in the college of Physicians and

Surgeons of the University of the State of New York”

for dissection. (Gibbs, 147)

Although hangings garnered large crowds and often

had a festive air about them, the actual act was far

from entertaining. The dying man’s neck did not

snap, rather he might take an agonizing forty-five

minutes to die of suffocation. His face became

purple. His legs jigged. His kidneys and bowels

relieved themselves. If relatives or friends of the

pirate were present, they might pull on his legs to

hasten his demise.

It was a tradition to publicly display the bodies of

the more notorious pirates as a warning to those

foolish enough to follow in the pirate’s footsteps.

The bodies of Calico Jack Rackham and two of his men

were hung in chains at Plumb Point, Bush Key, and

Gun Key on Jamaica.

After the tide had washed over Kidd’s body three

times, his corpse was retrieved, coated with tar,

and bound in chains. Then the blacksmith at Tilbury

stuffed it into a metal harness so he could hang it

up at Tilbury Point.14

No definitive time was given as to how long his

bones would be on display, but some accounts gave

the length as “for years.”

Kidd wasn’t the only pirate to be hanged twice. As John Gow “was turned

off, he fell down from Gibbet, the rope breaking by

the weight of some that pulled his leg. Although he

had been hanging for four minutes, he was able to

climb up the ladder a second time, which seemed to

concern him very little, and he was hanged again.”

(Gosse, 140-141) After his execution on 11 June

1725, they hung his body in chains at Greenwich.

An alternative to hanging a body in a gibbet was to

display just the deceased’s head on a spike in a

prominent location, often along the waterfront. This

happened to Pierre L’Orange after his execution in

Veracruz on 22 October 1683.

While

the normal punishment for pirates in Imperial China

was beheading, Zheng

Zhilong (Christian name Nicholas Iquan) might

have suffered a torturous death in 1661. Regents for

the Emperor of Hearty Prosperity (Manchu or Qing

dynasty) ordered him to be slowly sliced to death.

This involved making a thousand cuts to a person’s

extremities in a progressively inward fashion. Each

slice was cauterized to stem the bleeding and to

inflict additional pain. Before Zheng died, he would

also watch his torturers inflict the same punishment

on two of his sons.15 While

the normal punishment for pirates in Imperial China

was beheading, Zheng

Zhilong (Christian name Nicholas Iquan) might

have suffered a torturous death in 1661. Regents for

the Emperor of Hearty Prosperity (Manchu or Qing

dynasty) ordered him to be slowly sliced to death.

This involved making a thousand cuts to a person’s

extremities in a progressively inward fashion. Each

slice was cauterized to stem the bleeding and to

inflict additional pain. Before Zheng died, he would

also watch his torturers inflict the same punishment

on two of his sons.15

The last pirate hanged during the golden age of

piracy was Olivier

Levasseur (also known as La Buse or The

Buzzard), who was turned off on the beach at Bourbon

Island in the Indian Ocean in July 1730. The

attending crowd cheered as the deed was done.

Even today, execution remains a real possibility

when hunting pirates. After Somali pirates captured

Maersk

Alabama and took Captain Richard

Phillips hostage, U. S. Navy

SEAL snipers shot three pirates on 12 April

2009.

Some pirates defied the odds and lived past their

prime, dying of either natural causes or from old

age. Thomas Paine’s last piratical voyage began in

1708 when he was seventy-six years old. Sometime

after his return to New England, he was interred on

his estate in Connecticut. Philip Gosse, the pirate

historian, attempted to track down pirate

tombstones, but only succeeded in finding one that

was located in a cemetery in Dartmouth, England.

While Queen Anne sat on the throne, Captain Thomas

Goldsmith went a pirating and amassed quite a

fortune before he died in his bed in 1714. The

following inscription adorned his headstone:

Men that are virtuous serve the Lord;

And the Devil’s by his friends ador’d;

And as they merit get a place

Amidst the bless’d or hellish race;

Pray then ye learned clergy show

Where can this brute, Tom Goldsmith, go?

Whose life was one continual evil

Striving to cheat God,

Man and Devil.

(Gosse, 25)

|

|

Some pirates, who

turned aside from their nefarious pursuits, lived

productive lives until their deaths. Lionel

Wafer, a surgeon, died around 1705. His fellow

buccaneer William Dampier died on Colman Street in

London a decade later. Sometime after Lancelot

Blackburne retired, he returned to England and

became the Archbishop of York. When he passed away

on 23 March 1743, it was “a time of extreme cold.”

(Marley, Pirates, 1:48) He was laid to rest

at St. Margaret’s in Westminster. Red Legs

Greaves became a philanthropist, giving to

charities and public institutions. His death was

greatly mourned. Edward England, on the other hand,

lived an extremely impoverished life on Madagascar

before he passed away in 1720.

The fourth governor of French Saint-Domingue, Bertrand

D’Ogeron, Sieur de la Bouère, led buccaneers

on a disastrous raid to Puerto Rico in 1673. He

eventually returned to Paris, where on 21 January

1676, he died at the Sorbonne of “an incurable

diarrhea.” (Marley, Pirates, 1:298)

Although better known for his support of Charles II

in his bid to regain the throne of England, Prince Rupert of

the Rhine also participated in a bit of

plundering. In 1653, his fleet wrecked during a

storm near the Virgin Islands; his brother Maurice

died when his ship went down. Broken in spirit from

these losses, Rupert returned to England. He died in

his bed at Spring Gardens in 1682.

Perhaps the most famous buccaneer to die of natural

causes was Sir Henry Morgan. He succumbed to dropsy,

a result of being “much given to drinking and

sitting up late,” according to his physician. At the

time, he owned several properties in Jamaica and was

worth over £5,000. Captain Lawrence Wright of HMS

Assistance wrote in his journal in August

1688:

Saturday

25. This day about eleven hours noone Sir Henry

Morgan died, & the 26th was brought over

from Passage-fort to the King’s house at Port

Royall, from thence to the Church, & after a

sermon was carried to the Pallisadoes &

there buried. All the forts fired an equal

number of guns, wee fired two & twenty &

after wee & the Drake had fired, all the

merchant men fired. (Gosse, 227)

The most powerful pirate

of China spent her last days “leading a peaceful

life so far as [was] consistent with the keeping of

an infamous gambling house.” (Murray, 150) Zheng Yi

Sao (Cheng I Sao) negotiated her own

retirement in April 1810, receiving amnesty from the

Imperial Chinese government and keeping much of her

plunder. She died in 1844, at the age of sixty-nine

in Canton, China.

Benjamin Johnson tortured many of his victims until

they died. When he attacked the town of Busrah, he

slew the sheik and most of the residents before

returning to the Sultan of Ormus with the hold of