Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Oh To Be a

Pirate

by Cindy Vallar

Life

aboard a sailing ship was anything but comfortable.

Seamen lived in cramped and filthy quarters. Rats

gnawed through anything, including a ship’s hull.

Food spoiled or became infested, and fresh water

turned foul. One staple of most ships was hard tack,

which seaman often ate in the dark to avoid seeing

the weevils that infested the square biscuits. To

soften hardtack

and make it more palatable, cooks might soak and

boil them in rum and brown sugar to create a

porridge-like mixture.

Pirates restocked their food supplies by stealing

from other ships’ stores. In the Caribbean, they

also caught turtle

for fresh meat. Sea turtles were easily snared

on land and were kept alive in the ship’s hold until

needed. Their soft-shelled eggs were a popular

delicacy. Pirates’ recountings of their adventures

also mention fishing for dolphins, albacore tuna,

and other varieties of fish. One popular dish

was salmagundi

or Solomon Grundy. Similar to a chef salad, it

contained marinated bits of fish, turtle, and meat

combined with herbs, palm hearts, spiced wine, and

oil. This concoction was then served with

hard-boiled eggs, pickled onions, cabbage, grapes,

and olives. Pirates also ate yams, plantains,

pineapples, papayas, and other fruits and vegetables

indigenous to the tropics.

They drank bombo or bumboo, a mixture of rum, water,

sugar, and nutmeg. Rumfustian was another popular drink

that blended raw eggs with sugar, sherry, gin, and

beer. Pirates also enjoyed beer, sherry, brandy, and

port.

When

food was scarce, they resorted to more desperate

measures to stay alive. Charlotte de Berry’s crew

ran out of food and purportedly ate two slaves and

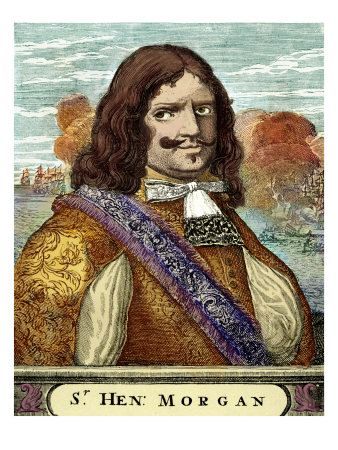

her husband to sustain them. In 1670, Sir Henry

Morgan’s crew ate their leather satchels. They

recommended cutting the leather into strips. After

soaking these, they tenderized them by beating and

rubbing the leather with stones. They scraped off

the hair, and then roasted or grilled the strips

before cutting them into bite-size pieces. The

recipe suggested serving them with a lot of water. When

food was scarce, they resorted to more desperate

measures to stay alive. Charlotte de Berry’s crew

ran out of food and purportedly ate two slaves and

her husband to sustain them. In 1670, Sir Henry

Morgan’s crew ate their leather satchels. They

recommended cutting the leather into strips. After

soaking these, they tenderized them by beating and

rubbing the leather with stones. They scraped off

the hair, and then roasted or grilled the strips

before cutting them into bite-size pieces. The

recipe suggested serving them with a lot of water.

Among artifacts

uncovered in shipwrecks, pirate havens, and other

areas frequented by pirates, archeologists have

found glass wine and brandy bottles, earthenware

beer bottles, pewter plates and tankards, and

silverware, especially knives and spoons. Forks were

a symbol of wealth and the few found may have been

part of pirate treasure.Pirates, however, preferred

to eat with their fingers.

Some pirate ships had galleys and some, like Captain

Kidd’s Adventure Galley, had none.

Instead, food was cooked in a cauldron with a brick

hearth that operated only during periods of calm

weather. It was located far from the magazine

to prevent accidental igniting of the gunpowder.

Left: Galley stove aboard Elizabeth

II in 1585 to Roanoke Island, an expedition

backed by Sir Walter Raleigh

Right: Portable galley as used aboard

Columbus's ships in 1492

(Source: Author)

Between the excitement of sighting sail and

weathering dangerous storms, pirates followed the

same dull routine that numbed seamen’s minds. Much

of their time was occupied with the care and

maintenance of their ships. They patched sails using

pickers (used to make small holes in canvas), seam

rubbers, needles, and sailmaker’s

palms (provided protection for the hand). They

spliced ropes with a fid. To keep the ship

watertight, they hacked old oakum from seams using a

jerry iron, drove new oakum

into the seams with a caulking iron, and then ladled

hot pitch into the seams to seal them tight.

Sometimes they sought the shelter of hidden coves to

careen their ships to remove the worms that bored

tiny holes in the hull, producing leaks, and to

scrape off barnacles that slowed the ship.

Tools used by ship's sailmaker

and rigger (left) and carpenter (right)

(Source: Author)

Pirates relaxed like other seamen. They played cards

or rolled dice, although most articles of agreement

forbade gambling on board ships to prevent arguments

that divided the crew or proved fatal to one or more

participants. At sea, they chewed tobacco rather

than smoked because of the ever-present threat of

fire, a serious fear aboard wooden ships. They

carved, sang, and danced jigs. When ashore, pirates

squandered their booty on drink, women, and games of

chance. They smoked clay pipes. Tavern keepers

served them beer and wine in black jacks, leather

tankards coated with pitch, or pewter tankards.

One popular pastime amongst pirates was the mock

trial. Each man played a part be it jailer, lawyer,

judge, juror, or hangman. This sham court arrested,

tried, convicted, and “carried out” the sentence to

the amusement of all.

No matter where they sailed, pirates frequented

friendly ports. One of the most infamous was Port Royal.

God-fearing people thought it the most wicked of

cities and believed that the earthquake

that brought about its destruction in 1692 was

payment for its sinfulness and debauchery. Tortuga

and Madagascar

also welcomed pirates.

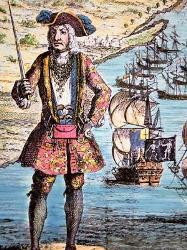

Ashore, some pirates

emulated gentleman merchants by wearing knee

breeches, stockings, embroidered waistcoats,

lace-trimmed shirts, long coats, and shoes with

silver buckles and high heels. A few wore powdered

wigs or ornate jewelry. They acquired these brightly

colored garments as shares of booty taken from

captured ships. Some pirates dressed like gentlemen

when facing their own executions by hanging: velvet

jackets, taffeta breeches, silk shirts and hose, and

felt tricornes. One of the best dressed pirates was

Bartholomew

Roberts, who dressed in a rich crimson damask

waistcoat and breeches, a red feather in his hat, a

gold chain round his neck, with a diamond cross

hanging to it. Ashore, some pirates

emulated gentleman merchants by wearing knee

breeches, stockings, embroidered waistcoats,

lace-trimmed shirts, long coats, and shoes with

silver buckles and high heels. A few wore powdered

wigs or ornate jewelry. They acquired these brightly

colored garments as shares of booty taken from

captured ships. Some pirates dressed like gentlemen

when facing their own executions by hanging: velvet

jackets, taffeta breeches, silk shirts and hose, and

felt tricornes. One of the best dressed pirates was

Bartholomew

Roberts, who dressed in a rich crimson damask

waistcoat and breeches, a red feather in his hat, a

gold chain round his neck, with a diamond cross

hanging to it.

While at sea, they usually wore one outfit until the

garments were no better than rags. Seamen favored

fearnoughts (short jackets of heavy blue or gray

cloth) or canvas coats (in foul weather), red or

blue waistcoats, plain or checked shirts (often blue

and white), and petticoat breeches (canvas trousers

cut a few inches above one’s ankles). These were

often coated with tar to make them waterproof and to

deflect sword thrusts. Shoes were worn on shore, but

rarely aboard a ship. To protect themselves from the

hot sun, they wore knotted scarves, tricorn hats, or

various styles of caps. The Ilanun of

Borneo, the most feared pirates in the waters

around Southeast Asia during the mid-1800s, wore

sarongs and embroidered belts.

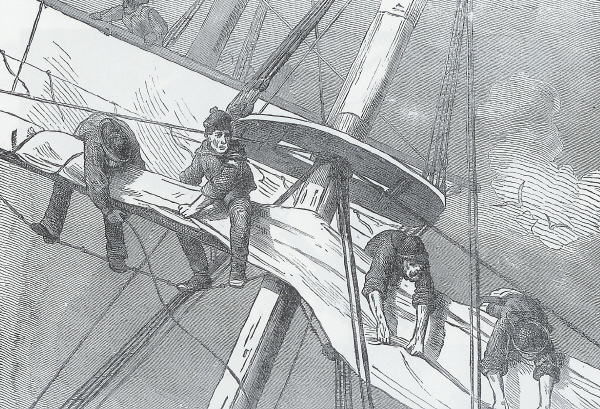

Most men who chose to go to sea did so at a young

age. Life at sea required stamina and dexterity that

older men no longer possessed. Seamen hauled on wet

ropes during the day and at night. Aloft, they

handled heavy sails in calm or stormy weather. They

manned pumps for hours on end. Their damp and dark

quarters smelled of bilgewater, tar, and unwashed

bodies as well as the assorted livestock that

provided them with fresh meat. They spent weeks,

months, and sometimes years at sea far from home.

They weathered storms, attempted to steer clear of

uncharted shoals, and worried about having

sufficient food and water until they made their next

port.

Aloft

furling a sail

(Source: Dover's Natuical Illustrations)

Some who crewed naval vessels did so against their

wishes. A common practice, especially in Britain,

was to fill crews short-handed from illness or

chronic desertion by pressing landsmen into service.

While in port, these men were shackled to prevent

their escape. Seamen, whether pressed or not, found

life aboard ships of the Royal Navy deplorable.

Wages were low. Corruption impacted the quantity and

quality of food served them. Mistakes or infractions

were countered with violent discipline. Poor

ventilation and cramped quarters ensured that

epidemics swept through the crew, killing many.

If such was the life endured by seamen, why did they

risk their lives further by turning pirate? Until

1856 when most countries signed the Declaration

of Paris, governments supplemented their

navies by issuing letters of

marque. With these documents, captains and

their crews “legally” plundered enemy shipping. The

profits realized by such ventures encouraged others

to become privateers.

The problem was that when the war ended, those same

governments had no use for the privateers, who often

found themselves unemployed. Piracy offered them a

choice between starvation, beggary, or thievery and

possible riches beyond their wildest dreams, which

outweighed the threat of execution if caught and a

short life-expectancy rate.

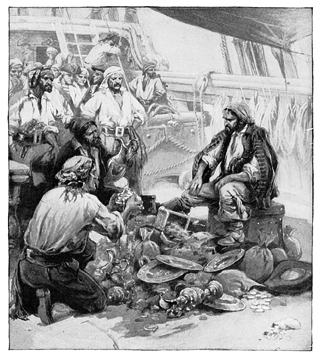

Another aspect to the financial

rewards was that pirates owned a share of the spoils

they captured. Privateers turned over their booty to

the governments that licensed them. Although they

received a share after the goods were sold, that

money was either a long time in coming or a paltry

amount when compared to the risk taken. Treasure –

Latin American gold, Bolivian silver, and Asian

silks, spices, and gold – lured many to turn pirate. Another aspect to the financial

rewards was that pirates owned a share of the spoils

they captured. Privateers turned over their booty to

the governments that licensed them. Although they

received a share after the goods were sold, that

money was either a long time in coming or a paltry

amount when compared to the risk taken. Treasure –

Latin American gold, Bolivian silver, and Asian

silks, spices, and gold – lured many to turn pirate.

Some saw piracy as a means of escaping the grueling

work and terrible conditions that seamen endured. In

addition to the filth, cramped quarters, and

insufficient or spoiled food and fresh water,

dampness permeated their lives. Each new port

exposed them to new diseases that often swept

through the crew because they ate, slept, and worked

in close quarters. Disease

– including scurvy, dysentery, tuberculosis, typhus,

and smallpox – killed half of all seamen.

Other men wished to escape the cruelties inflicted

on them for minor and major infractions. Piracy

promised them a better way of life, the chance to

make their fortunes, and the opportunity to leave

the drudgery of life on land. As pirates, all men

were equal. No longer did one man outrank another.

The crews chose their captains, and signed articles of

agreement to ensure that everyone earned a

share of any prize taken. Such freedom was

unavailable to men who remained on the right side of

the law.

In some parts of the world, people became pirates

out of economic

necessity. Fishing and boating were their

means of livelihood. If the fishing dried up, they

needed to find another way to earn enough money to

live, and so resorted to smuggling and/or piracy.

This has been true for centuries along the southeast

coast of China. It also happened to the buccaneers

and privateers who worked in the logwood

industry of Honduras. After the Peace of Utrecht,

the Spaniards destroyed their livelihood, leaving

them to starve or join one of the pirate crews that

sailed the Caribbean.

For many centuries, Europe was plagued by wars

interspersed with times of peace. When at war,

nations recruited men to serve in their navies. When

peace came, these same men were forced to find other

employment or die of starvation. Those who knew only

the trade of sailing often turned to piracy. Such

was the case following the War of the

Spanish Succession. Prior to the cessation of

hostilities, the Royal Navy employed 53,000 men.

With peace at hand, they dismissed 40,000 of those

seamen. At about this same time (1715-1725), there

was an upsurge in piracy along coasts bordering the

Atlantic Ocean. Most English-speaking pirates came

from the Royal Navy, merchant ships, and privateers.

Between 1716 and 1718, there were 1,800 to 2,400

pirates. By 1726, those numbers dropped to 1,000 to

1,500 pirates.

That’s not to say all men who turned to piracy did

so willingly. When pirates captured a ship, they

either killed those lacking seamanship skills

or put them ashore. Able-bodied seamen, especially

those who possessed a specialized skill (surgeons,

carpenters, coopers, musicians) had no such option.

Pirate crews always needed men familiar with ships

and the sea, and so forced them to join in their

nefarious trade. During the golden age

of piracy, many pirates who sailed in

Caribbean waters were forced men.

Whether willing or not, pirates hailed from many

nations. While most were illiterate and came from

poor families, some – like Stede

Bonnet and Doctor John

Hincher – were educated gentlemen. During the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the average

pirate prowling the Caribbean was in his twenties.

Few pirates plied their trade for more than ten

years. The more famous, like Blackbeard and Captain

Kidd, were pirates for no more than two or three

years. Only a small number lived long enough to

enjoy their ill-gotten wealth.

Review

Copyright ©2001 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |