Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Friends and

Enemies

by Cindy Vallar

Meet the friends of pirates

Patrons, Merchants, Government Officials, Women

Meet

the Enemies

Pirate Hunters, Government Officials, Witnesses,

Preachers, Victims

The Friends

Patrons

Patrons were men, and on

occasion women, who had the finances necessary to

back piratical ventures. Some also acquired

significant power and influence to protect the

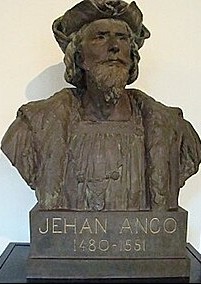

pirates from the law. Jean Ango,

who lived in Dieppe, France, from about 1480 to

1551, sponsored sailing ventures that were both

legal and illegal. Through outright ownership or as

a member of a syndicate, he controlled many of the

vessels in the region. His ships attacked others

bound from the Indies, and with his earnings he

bribed bankers, judges, and military officers to

protect him and thus controlled the local

government. Eventually, he was imprisoned for

misconduct in office.

Sir George

Carey, the second Baron Hunsdon, promoted

piracy in England. The eldest son of Lord Admiral

Charles Howard’s brother-in-law and kinsman to Queen

Elizabeth I, Carey became Captain-General of the

Isle of Wright and Vice-Admiral of Hampshire. As

such, he fenced booty and other items acquired

through illegal means. Any victim who dared to seek

justice through the Admiralty Court in London lost

his case because Carey influenced or bribed the

judges. Between 1587 and 1591, he financed at least

three pirate fleets that plundered the West Indies.

The Killigrews

of Cornwall also supported piracy during the

sixteenth century. Various members of this

family fenced stolen goods, while a few actually

became pirates.

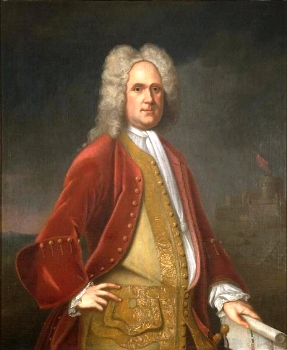

Frederick

P. Philipse was one of New York’s richest and

most politically influential merchants of the last

decade of the seventeenth century. He financed

numerous pirate ventures, including that of Adam

Baldridge’s trade with the pirates of Madagascar.

Philipse’s final shipment to St. Mary’s in 1698,

carried salt, arms (guns, pistols, muskets, knives),

gunpowder, flints, alcohol (beer, wine, rum),

looking glasses, sewing implements (thimbles,

scissors, thread, 3,000 needles), buttons, ivory

combs, cotton candlewicks, tobacco pipes, hats, and

shoes. These items were sold or traded for gold,

silks, spices, and slaves. His son, Adolphus, also

participated in the pirate brokering business.

Nor were the Philipses the only colonial

entrepreneurs to fund pirate ventures. Men just like

them lived in Philadelphia, Boston, Newport, and

Charleston. They functioned as legitimate importers

and merchants, but also brokered stolen goods.

They incorporated their fees into the value of the

cargoes pirates brought them, and then sold those

goods at a high profit.

Merchants

Merchants purchased

ill-gotten gains from pirates in hopes of making

greater profits than they could through legal means.

Some wealthier merchants openly financed pirate

expeditions. Forbidden to manufacture anything

themselves, British colonists had to import all

manufactured goods at high prices. Since pirates had

these items (especially scarce goods from foreign

countries), and the colonists didn’t have to pay

high import duties, they welcomed the pirates.

According to some estimates, pirates brought

£100,000 into New York’s economy.

Once a pirate himself, Adam Baldridge fenced and

traded with pirates for six years. He arrived on St. Mary’s

Island in Madagascar, a haven for pirates, in

early 1691, and built a trading post, a house,

storehouse, and log fortress protected by six

cannons on the small island surrounded by a lagoon.

He also erected a second fortification near the

harbor with about twenty-two guns. Pirates exchanged

gold and other booty for the supplies they needed.

Wine, for example, sold in St. Mary’s for fifteen

times its New York price. Over the next six years,

Baldridge built a lucrative business, which he sold

to Edward Welch in 1698.

Between 1697 and 1699, several merchant ships put in

at St. Mary’s laden with cargo for trade with the

pirates. Under the command of Richard Glover, Amity

arrived in May of 1697. Unfortunately, the crew

of Resolution stole the cargo, which

resulted in a loss for Amity’s owners,

the Governor of Barbados and several others. Captain

Thomas Mostyn arrived aboard Fortune in

June. When he returned to New York in 1698, he

brought with him fourteen pirates who had decided to

retire.

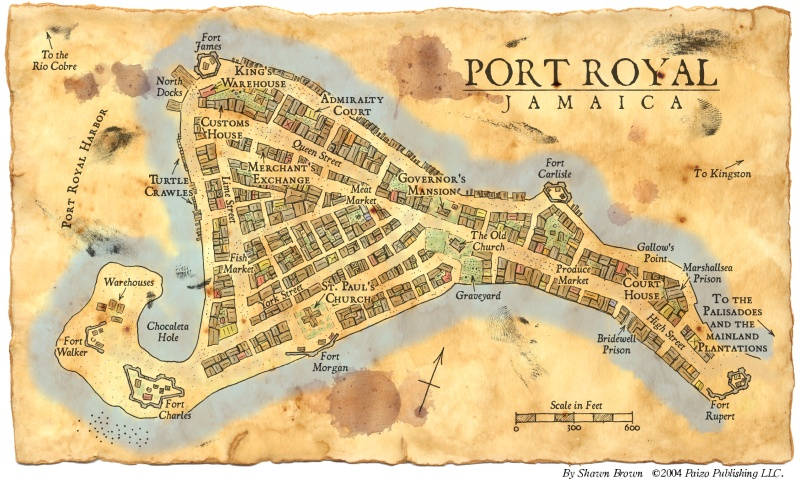

Port Royal,

another pirate haven, catered to many pirates during

the days of the buccaneers. One of the town’s more

genteel establishments

was Barre’s Tavern, which served “silabubus [sic],

cream tarts and other quelque choses.” (Marley) John

Starr ran the biggest brothel in Port Royal. His

girls included twenty-one whites and two blacks.

Government

Officials

Members of the government

tended to fall on both sides of the piracy issue.

Some were friends. Some proved to be enemies.

Between 1581 and 1583, Francis Hawley, an English

customs official and the deputy of Sir Charles

Christopher Halton at Corfe Castle, received stolen

merchandise from pirates. Among those were Stephen

Heynes (also known as Stephen Carless), who

often said he “had better friends in Englande then

eanye alderman or merchants of London” and William

Valentine (aka Vaughan), who once captured a cargo

of Bibles. (Rogozinski)

One

frequent abuse of power stemmed from the letters of

marque the colonial governors issued. Thomas Tew

received his commission from Governor Benjamin

Fletcher of New York. Fletcher, a colonel in

the English Royal Army, became governor in August

1692, and also received a two-year appointment as

the Governor of Pennsylvania and commander of the

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Jersey militias.

In return for the privateering commission, Tew gave

the governor a promissory note of £300 to insure

that he did nothing illegal, yet he went to the Red

Sea and captured an Arab ship laden with gold that

netted him £8,000 and each pirate £1,200. One

frequent abuse of power stemmed from the letters of

marque the colonial governors issued. Thomas Tew

received his commission from Governor Benjamin

Fletcher of New York. Fletcher, a colonel in

the English Royal Army, became governor in August

1692, and also received a two-year appointment as

the Governor of Pennsylvania and commander of the

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Jersey militias.

In return for the privateering commission, Tew gave

the governor a promissory note of £300 to insure

that he did nothing illegal, yet he went to the Red

Sea and captured an Arab ship laden with gold that

netted him £8,000 and each pirate £1,200.

That Fletcher, and others like him, consorted with

pirates was not a secret. Fletcher invited Tew to

dine with his family and accepted a gold watch from

the pirate. When Edward Coates wished to bring his

plundered goods into New York, Fletcher wanted £700.

Instead, Coates gave him the entire ship, which

Fletcher sold for £800. When the governor received a

reprimand for selling letters of marque to pirates,

he wrote, “It may be my unhappiness, but not my

crime if they turn pirates.” (Marx) Yet he did know,

for his wife and daughters wore silk gowns and

jewelry Tew acquired from his attack on ships of the

Mogul of India.

Governor William

Markham of Pennsylvania was a “steddy friend”

to pirates. He approved of his daughter’s marriage

to James Brown, who had sailed with Henry Every.

Markham helped his son-in-law secure a seat in the

assembly and protected him for £100. Another pirate,

Captain Sneed, paid the governor slightly more money

to become a justice of the peace. He did not,

however, prove a friend. He prosecuted pirates and

accused Markham of consorting with pirates.

Robert Livingston, an entrepreneur in New York,

assisted William

Kidd in acquiring sponsors for the

privateering voyage that resulted in Kidd being

declared a pirate and murderer. One supporter was

Lord Bellomont, a member of Parliament. The other

members of the syndicate included four lords

(Somers, Orford, Romney, and Shrewsbury) and a

director of the East India Company, Edmund Harrison.

Jacques Nepveu, Sieur de Pouançay, was the fifth

governor of Tortuga and Saint-Domingue. To revive

the economy, he granted letters of marque to pirates

on the condition that they returned to the island

with their prizes, and he maintained this policy

even after peace was declared in 1679. During his

tenure, he employed over one thousand pirates,

including the Chevalier de Grammont, Pierre le

Picard, and Jean Rose. Jean-Baptiste

Ducasse, the seventh governor of

Saint-Domingue, led French pirates in raids against

Jamaica in 1694 and Cartagena in 1697.

Women

Few

pirates actually married. Out of a sampling of 521,

only twenty-three had wives. Those convicted of

their crimes often asked for their parents’

forgiveness, but rarely mentioned wives and

children. There were exceptions, though. In 1709,

forty-seven women and others kinsmen petitioned

Queen Anne to pardon the pirates of Madagascar. William

Baugh wanted to marry the daughter of Henry

Skipwith, commander of the fort at Kinsale, Ireland.

Baugh bribed Mrs. Skipwith with gifts of silverware,

linen, and canvas to gain her daughter’s hand and to

secure protection from prosecution. William

Dampier married, but rarely mentioned his wife

in his journals and spent little time in England. Stede

Bonnet supposedly became a pirate to escape

his nagging wife. Henry

Morgan and William Kidd both married and had

children. John Criss,

of Ireland, left behind three wives upon his death. Few

pirates actually married. Out of a sampling of 521,

only twenty-three had wives. Those convicted of

their crimes often asked for their parents’

forgiveness, but rarely mentioned wives and

children. There were exceptions, though. In 1709,

forty-seven women and others kinsmen petitioned

Queen Anne to pardon the pirates of Madagascar. William

Baugh wanted to marry the daughter of Henry

Skipwith, commander of the fort at Kinsale, Ireland.

Baugh bribed Mrs. Skipwith with gifts of silverware,

linen, and canvas to gain her daughter’s hand and to

secure protection from prosecution. William

Dampier married, but rarely mentioned his wife

in his journals and spent little time in England. Stede

Bonnet supposedly became a pirate to escape

his nagging wife. Henry

Morgan and William Kidd both married and had

children. John Criss,

of Ireland, left behind three wives upon his death.

The most commonly thought-of relationship between

pirates and women involved informal sexual liaisons.

Baptiste Ingle, a pirate in Captain Robert

Stephenson’s crew, came to Whiddy Island in

1612. He often made “merry with a young woman

that lay at Ballygubbin.”(Bandits at Sea) His

fellow pirates said he intended to wed the colleen,

but the wooing ended abruptly after he absconded

with £100 he stole from his comrades.

Most pirates, however, had less permanent liaisons

with women. Prostitution was a thriving business in

the ports or havens where they visited. In 1740,

Charles Leslie wrote: “Wine and women drained their

wealth to such a degree that, in a little time, some

of them became reduced to beggary. They have been

known to spend two or three thousand pieces of eight

in one night; and one gave a strumpet five hundred

to see her naked.” (Cordingly) Mary

Carleton, the German Princess, was Port

Royal’s most famous prostitute. Born in

Canterbury, England, she arrived in that city soon

after her conviction in 1671 for theft and bigamy. Zheng Yi

Sao (1775-1844) was a prostitute in Canton,

China before she married Zheng Yi in 1801, and

helped him create a powerful federation of pirates.

Not all women that consorted with pirates, however,

were prostitutes. They were legitimate “traders,

truckers or vitelers,” some of whom were widows who

acquired the business upon their husbands’ deaths. (Bandits

at Sea) Other women held jobs men did

not. An Irish seamstress received a bolt of

striped cloth in 1610 to make John Bedlake a

waistcoat. Thomas Barlowe’s wife sold beer to

pirates in Leamcon, Ireland. In nearby Long Island,

Black Dermond and his wife exchanged food for wine,

canvas, broadcloth, steel, and other goods. Three

Bantry Bay women were accused of receiving stolen

goods from Dutch pirates in 1625. Mrs. Thibault

Suxbridge operated a Dublin safe house where friends

and relatives found sanctuary from the authorities.

In July 1612, her brother, Henry Orange, stayed

almost a week until he found a ship to England.

William Baugh also stayed in the house, but fled

after he stole jewels and diamonds.

The Enemies

Pirate

Hunters

After

the golden age of Piracy ended around 1730, the

number of pirates declined dramatically, but hey did

not cease preying on unwary vessels. Significant

losses to merchants and shipowners, as well as

frequent victims’ complaints, spurred the American

and British governments to clamp down on piracy. In

1822, the United States Navy formed a special

squadron to carry out this mission. “The Mosquito

Fleet” established its base on Key West under the

command of Commodore David Porter, and within three

years, pirates ceased to plague maritime commerce in

Caribbean and American waters. Porter, however, was

not the first of the pirate hunters. After

the golden age of Piracy ended around 1730, the

number of pirates declined dramatically, but hey did

not cease preying on unwary vessels. Significant

losses to merchants and shipowners, as well as

frequent victims’ complaints, spurred the American

and British governments to clamp down on piracy. In

1822, the United States Navy formed a special

squadron to carry out this mission. “The Mosquito

Fleet” established its base on Key West under the

command of Commodore David Porter, and within three

years, pirates ceased to plague maritime commerce in

Caribbean and American waters. Porter, however, was

not the first of the pirate hunters.

Perhaps the best known was Lieutenant Robert

Maynard of HMS Pearl. His target? Blackbeard!

Virginia Governor Alexander

Spotswood authorized the expedition, and he

thought Maynard “an experienced officer and a

gentleman of great bravery and resolution.”

(Cordingly) If successful, the lieutenant and

his men would receive “. . . For Edward Teach,

commonly called Captain Teach, or Blackbeard, 100

Pounds, for every other Commander of a Pyrate Ship,

Sloop, or Vessel, 40 pounds; for every Lieutenant,

Master, or Quarter-Master Boatswain, or Carpenter,

20 Pounds; for every other inferior Officer, 15

Pounds, and for every private Man taken on Board

such Ship, Sloop, or Vessel, 10 Pounds.” (Cordingly)

According to the Boston

News-Letter, “Maynard and Teach . . .

begin the fight with their swords, Maynard making a

thrust, the point of his sword went against Teach’s

cartridge box, and bended it to the hilt. Teach

broke the guard . . . and wounded Maynard’s fingers

but did not disable him, whereupon he jumped back

and threw away his sword and fired his pistol which

wounded Teach . . . one of Maynard’s men being a

Highlander, engaged Teach with his broad sword, who

gave Teach a cut on the neck, Teach saying well done

lad; the Highlander replied, If it be not well done,

I’ll do it better. With that he gave him a second

stroke, which cutt off his head, laying it flat on

his shoulder.” (Cordingly)

Another pirate hunter succeeded in capturing several

notorious pirates of the golden age, but few know

his name. Captain Jonathan

Barnett attacked the pirate sloop late in the

evening of 22 October 1720. “. . . [T]he women

screamed, fighting like hellcats as they shot their

pistols and swung their cutlasses, refusing to give

up peacefully.” (Eastman) In the end, however,

Barnett and his men subdued Calico Jack

Rackham, Anne Bonny,

Mary Read,

and the other pirates in the crew and returned them

to Jamaica to await trial.

.jpg)

Benjamin Cole's depiction of

Anne Bonny and Mary Read from A

General History of the Robberies and Murders

of the Most Notorious Pyrates

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

Bartholomew

Roberts, one of the most successful pirates,

met a different fate when he and his men tangled

with the British Royal Navy off the coast of Africa

in 1725. HMS Swallow, under the command of

Captain Chaloner Ogle, fired her guns loaded with

grapeshot that “. . . struck him [Roberts] directly

on the Throat. He settled himself on the Tackles of

a Gun, which one Stephenson, from the Helm,

observing, ran to his Assistance, and not perceiving

him wounded, swore at him, and bid him stand up, and

fight like a Man; but when he found his Mistake . .

. he gushed into Tears . . . .” (Defoe) Roberts’s

crew “threw him over-board, with his Arms and

Ornaments on, according to the repeated Request he

made in his Life-time.” (Defoe) For ending Roberts’s

reign of terror, Captain Ogle received a knighthood.

Once her ships from the New World became targets,

Spain instituted its own measures to curb piracy and

smuggling. For thirty-two years, beginning in 1667,

the Armada de Barlovento patrolled the sea

while the Guardacosta watched the coasts of

Spanish-held islands in the West Indies. They

weren’t supposed to venture far from port, but Spain

often failed to pay these privateers, and so they

took “all ships that have on board any frutos de

esas Iandis [fruits of these Indies]” and

“committed barbarous cruelties and injustices, and

better cannot be expected, for they are . . . a

mongrel parcel of thieves and rogues that rob and

murder all that come into their power without the

least respect to humanity or common justice.”

(Governor Thomas

Lynch in letter to superiors in London, 1684,

Marley)

Not all Guardacosta were like the pirates

themselves. Pedro de Castro patrolled the Gulf of

Mexico. He helped to roust the logwood cutters, many

of whom were pirates, from Laguna de Términos in

1680. Almost two decades earlier, Esteban de Hoces

and Juan González Perales captured numerous vessels,

including the pirate ship Cabellero Romano.

Another pirate hunter was Mateo Alonso de Huidobro

of the Spanish navy. His 218-ton frigate helped to

corner Henry Morgan’s flotilla during the

buccaneer’s raid on Maracaibo in 1669. Fourteen

years later, de Huidobro attended a banquet in

Veracruz while two unknown ships lurked nearby. The

governor, who believed the vessels to be peaceful

merchantmen from Caracas, disregarded de Huidobro’s

warning about pirates. In actuality, the ships were

captured Spanish prizes under the commands of Laurens de

Graaf and Jan Willems.

The pirates disembarked 800 men near Veracruz that

night, and before dawn surprised the garrison. De

Huidobro rallied the guards at the governor’s

palace, but was slain on 18 May.

Henry Morgan's destruction of

the Spanish fleet at Maracaibo in 1669

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

Although some hunters were naval personnel, reformed

pirates also hunted their own kind. One such example

was Benjamin

Hornigold, a fierce and proficient pirate who

sought haven in New

Providence in the Bahamas. His fellow pirates

held him in high esteem, and he trained many,

including Blackbeard, to follow in his footsteps.

Hornigold took the king’s pardon in 1718, and

thereafter ruthlessly hunted pirates who refused to

change their ways. After he captured Charles

Vane’s sloop, Governor Woodes

Rogers wrote: “Captain Hornigold having proved

honest, disobliged his old friends by seizing this

vessel and it divides the people here and makes me

stronger than I had expected.” (Lee) Although he

failed to capture Vane, Hornigold did bring in John

Auger and seven others, who eventually were hanged

for their crimes.

Government

Officials

The commissions to hunt

pirates came from colonial governors, who abhorred

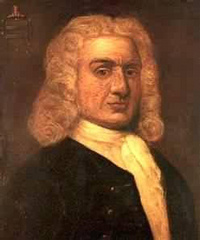

piracy. When Sir Thomas Lynch became governor of

Jamaica, he arrested his predecessor, Sir Thomas

Modyford, for authorizing the raid on Panama,

and Henry Morgan, for carrying out the attack. Both

were sent to England, where Modyford spent two years

in prison, but Morgan’s influential friends gained

his release. When news of Modyford’s imprisonment

reached the pirates, they avoided Jamaica. Three

years later, Morgan returned with a knighthood and

an appointment as lieutenant governor of the island.

Lynch resigned and left Jamaica. In 1682, King

Charles II reappointed Lynch as governor and he once

again pursued pirates. After a jury acquitted Joseph

Bannister of piracy, Lynch became so

exasperated he succumbed a week later.

From time to time, England sent officials to her

colonies to assess the corruptness of government

officials. Edmund

Randolph, a surveyor-general of Customs in

America, found that almost every governor and

official wasn’t “fit for Office” and every colony

was “a Receptacle of Pyrates.” He named two

exceptions, Virginia and her governor, who were

“truly zealous to suppress Pyracy and illegal

Trade.” (Marx) In 1699, Governor Nicholson

issued an arrest warrant for several pirates: “Tee

Wetherly, short, very small, blind in one eye, about

eighteen; Thomas Jameson, cooper, Scot, tall,

meagre, sickly look, large black eyes, twenty;

William Griffith, short, well set, broad face,

darkest hair, about thirty.” (Marx) The following

year, Nicholson played a significant role in

bringing to justice the French pirate Louis

Guittar and seventy others.

John Valentine of Rhode Island believed “[t]his sort

of Criminals are engag’d in a perpetual War with

every Individual” and prosecuted thirty-six pirates

in 1723. Five years earlier, South Carolina’s

Attorney General Richard Allen defined piracy as “a

Crime so odious and horrid in all its Circumstances,

that those who have treated on that Subject have

been at a loss for Words and Terms to stamp

sufficient Ignominy upon it.” (Rediker)

As the governor of

Jamaica, Sir Nicholas Lawes presided over the trials

of Calico Jack Rackham (16-17 November 1720) and

Anne Bonny and Mary Read (28 November 1720). Serving

on the court with Lawes were five counselors, a

chief justice, two naval captains, the

receiver-general, the secretary, and the collector.

After explaining how and why Lawes had the right to

assemble the court, the register read the charges

against Bonny and Read. Once the accused pled not

guilty, he called witnesses to prove otherwise.

Although not permitted to be represented by counsel,

the accused could call witnesses on their behalf, or

ask questions of prosecution witnesses. Bonny and

Read opted to do neither. The court deliberated

their fates in the presence of the register, then

reconvened. Lawes pronounced their sentences: “You .

. . are to go from hence to the place from whence

you came, and from thence to the place of execution;

where you shall be severally hanged by the neck till

you are severally dead. And God of his infinite

mercy be merciful to both your souls.” (Cordingly) As the governor of

Jamaica, Sir Nicholas Lawes presided over the trials

of Calico Jack Rackham (16-17 November 1720) and

Anne Bonny and Mary Read (28 November 1720). Serving

on the court with Lawes were five counselors, a

chief justice, two naval captains, the

receiver-general, the secretary, and the collector.

After explaining how and why Lawes had the right to

assemble the court, the register read the charges

against Bonny and Read. Once the accused pled not

guilty, he called witnesses to prove otherwise.

Although not permitted to be represented by counsel,

the accused could call witnesses on their behalf, or

ask questions of prosecution witnesses. Bonny and

Read opted to do neither. The court deliberated

their fates in the presence of the register, then

reconvened. Lawes pronounced their sentences: “You .

. . are to go from hence to the place from whence

you came, and from thence to the place of execution;

where you shall be severally hanged by the neck till

you are severally dead. And God of his infinite

mercy be merciful to both your souls.” (Cordingly)

A sentence of death required the building of a

scaffold for the hanging of the prisoners. John

Eles, a carpenter, built five between September 1724

and May 1725. His services cost the government £25.

Not all pirates danced the hempen jig. Just before

the signal to hang nine

pirates who had taken the king’s pardon but

returned to their lives of crime, Governor Woodes

Rogers “thought fit to order George Rounsivel to be

untied, and when brought off the stage, the butts

having ropes about them were hauled away, upon which

the stage fell and the eight swang off.” (Cordingly)

Witnesses

A trial inevitably meant

victims of piracy testified against the pirates who

had attacked them. Thomas Spenlow of Port Royal

testified against Rackham and his crew. After the

pirates had fired upon Spenlow’s schooner, they

“boarded him, and took him; and took out of the said

schooner, fifty rolls of tobacco, and nine bags of

piemento and kept him in their custody about

forty-eight hours, and then let him and his schooner

depart.” (Cordingly) Two French witnesses, through

an interpreter, testified, “That Ann Bonny . . .

handed Gun-powder to the Men, That when they saw any

Vessel, gave Chase, or Attacked, they wore Men’s

Cloaths; and, at other Times, they wore Women’s

Cloaths; That they did not seem to be kept, or

detain’d by Force, but of their own Free-Will and

Consent.” (Eastman) One of the most damaging

witnesses against the lady pirates was Dorothy

Thomas. “[T]he…prisoners at the bar, were then on

board the said sloop, and wore mens jackets, and

long trousers, and handkerchiefs tied about their

heads . . . each . . . had a machet and pistol in

their hands, and cursed and swore at the men, to

murder the deponent . . . to prevent her coming

against them . . . .” She knew they were women

“by the largeness of their breasts.” (Cordingly)

Sometimes a witness provided key evidence that

altered the court’s opinion of the guiltiness of the

prisoner before them. After pirates captured Aaron Smith,

they forced him to go on the account. He eventually

escaped but was arrested and tried as a pirate three

times (once in Cuba and twice in England). At one

trial, he called Miss Sophia Knight, his fiancée as

a witness. Holding a letter, she wept as she

testified. “I have been intimately acquainted with

the prisoner for more than three years. This letter

is from him. It is the last that ever reached me. It

is dated Oct., 1821. After the date of the letter, I

expected on the prisoner arriving in England that I

should become his wife. It was so arranged.” (Captured

by Pirates) The jury found Smith not guilty.

Later, he returned to the sea and pirates almost

captured him again.

Another witness against

pirates, one who usually didn’t testify, was the

informer. Some sought revenge for a slight; others

thought it their civic responsibility. Most did it

for a price. Such was the case involving Jean

and Pierre

Laffite in Louisiana in 1811. “The informant

told Gregory [Lieutenant Francis Gregory, commander

of Gunboat No. 162] of the privateers routes and

said he expected some pirogues to be leaving the

coast shortly with prize goods . . . .”

(Davis) Gregory followed up on the lead, and

even though the pirates escaped, he salvaged 66% of

the prize vessel’s cargo, which included “more than

6,300 packages of writing paper” and brandy. (Davis) Another witness against

pirates, one who usually didn’t testify, was the

informer. Some sought revenge for a slight; others

thought it their civic responsibility. Most did it

for a price. Such was the case involving Jean

and Pierre

Laffite in Louisiana in 1811. “The informant

told Gregory [Lieutenant Francis Gregory, commander

of Gunboat No. 162] of the privateers routes and

said he expected some pirogues to be leaving the

coast shortly with prize goods . . . .”

(Davis) Gregory followed up on the lead, and

even though the pirates escaped, he salvaged 66% of

the prize vessel’s cargo, which included “more than

6,300 packages of writing paper” and brandy. (Davis)

Preachers

One thinks

of a minister as preaching to his flock and

comforting the sick, but some clergy added another

task to their duties – extracting confessions from

pirates and persuading them to repent before they

died. The Reverend Paul Lorrain, the Ordinary

(prison chaplain) at Newgate

Prison instructed pirates in Christianity. For

the three Sundays prior to their executions, Lorrain

preached twice a day. Of one unrepentant pirate,

Alexander Dolzell, a forty-two-year-old Scot,

Lorrain wrote, “He was so brutish and so obstinate

that he would not be satisfied with anything I

offered to him in this matter, saying, he hated to

see my face, and would not attend in the Chapel . .

. nor receive any public or private admonition from

me . . . .” (Cordingly) Just before his hanging, and

while Lorrain prayed, Dolzell repented and

apologized. One thinks

of a minister as preaching to his flock and

comforting the sick, but some clergy added another

task to their duties – extracting confessions from

pirates and persuading them to repent before they

died. The Reverend Paul Lorrain, the Ordinary

(prison chaplain) at Newgate

Prison instructed pirates in Christianity. For

the three Sundays prior to their executions, Lorrain

preached twice a day. Of one unrepentant pirate,

Alexander Dolzell, a forty-two-year-old Scot,

Lorrain wrote, “He was so brutish and so obstinate

that he would not be satisfied with anything I

offered to him in this matter, saying, he hated to

see my face, and would not attend in the Chapel . .

. nor receive any public or private admonition from

me . . . .” (Cordingly) Just before his hanging, and

while Lorrain prayed, Dolzell repented and

apologized.

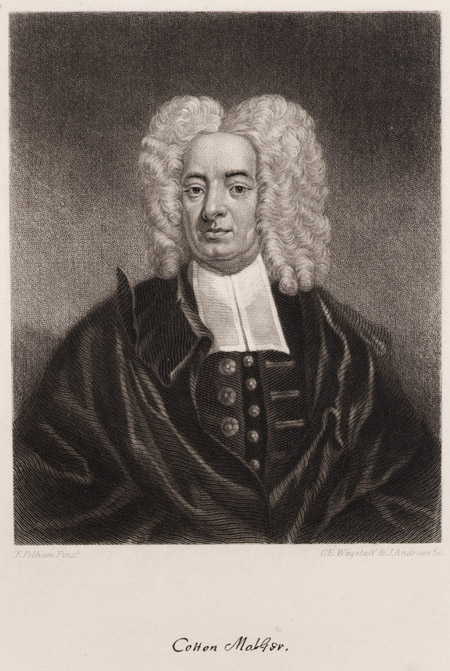

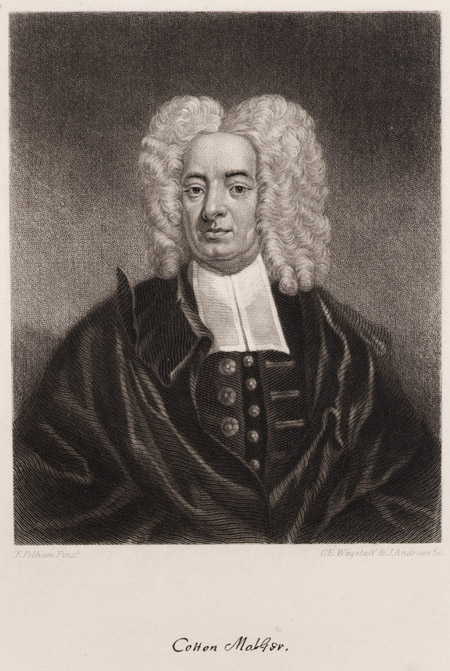

Cotton

Mather, the minister of Old North Church in

Boston (1685-1722), considered pirates to be “the

Common Enemies of Mankind” and that all nations

should take whatever means were necessary to

“extirpate them out of the World.” (Rediker) Mather

often preached against piracy from his pulpit and

persuaded convicted pirates to confess. Determined

to show them the errors of their ways, he played a

significant role at both their trials and

executions. He preached daily sermons to John Quelch

and his men, and prayed with them, “and they were

catechised; and they had many occasional

exhortations.” (Cordingly) To the survivors

of Whydah, he said, “All the riches

which are not honestly gotten must be lost in a

shipwreck of honest restitution, if ever men come

into repentance and salvation.” (Cordingly) Mather

also accompanied pirates, including William

Flynn, as they walked to the scaffold and

later published their conversations in pamphlets.

Victims

Those most affected by

piracy were those who fell victim to the pirates.

Some eventually had the opportunity to see justice

done, having escaped with just the loss of their

valuables, but others weren’t so lucky. Barbary

corsairs raided Baltimore,

Ireland in 1631 and enslaved almost the entire

population – one hundred men, women, and

children. Only two victims, Joan Brodbrooke

and Ellen Hawkins, returned home after being

ransomed fifteen years later.

Christian prisoners sold into

slavery in Algerian square by Jan Luyken

(1684)

(Source: Wikimedia

Commons)

In October 1809, Chinese pirates captured more than

200 women and children from a single village. Richard

Glasspoole, already a captive, witnessed the

attack. “They were unable to escape with the men

owing to that abominable practice of cramping their

feet . . . 20 of these poor women were sent on board

the vessel I was in; they were hauled . . . by the

hair and treated in a most savage manner . . .

during [five or six days] about an hundred of the

women were ransomed; the remainder were offered for

sale . . . for 40 dollars each. . . . Several . . .

leaped overboard and drowned . . . rather than

submit to such infamous degradation.” (Bandits at

Sea)

Doña Augustin de Rojas of Portobello had the

misfortune of falling into the hands of buccaneers

in 1668. Henry Morgan had her stripped naked and

then forced her to stand in an empty wine barrel.

The buccaneers filled the barrel with powder. One of

them held a lit fuse to her face and demanded she

tell them where the treasure was hidden. Some women

endured repeated rapes, and if they survived and

returned to society, society often considered them

damaged goods.

Men, too, suffered. Several buccaneers were noted

for their cruelty, especially when dealing with

Spaniards. Alexandre

Exquemelin wrote, “Among other tortures . . .

one was to stretch their limbs with cords, and at

the same time beat them with sticks and other

instruments. Others had burning matches placed

betwixt their fingers, which were thus burnt alive.

Others had slender cords or matches twisted about

their heads, till their eyes burst out of the

skull.”

Contrary to popular belief, Blackbeard didn’t

inflict similar terrors on his victims. “If a victim

did not voluntarily offer up a diamond ring,

Blackbeard chopped it off, finger and all. This

nearly always impressed the victim, who could be

counted on to impress all to whom he related his

experience. These tactics also saved time, but their

most important function was to help spread the word

that, while Blackbeard could be merciful to those

who cooperated, woe to those who did not.” (Lee)

To learn more I suggest:

Bandits

at Sea: A Pirates Reader. New York

University, 2001.

Captured by

Pirates: 22 Firsthand Accounts of Murder and

Mayhem on the High Seas. Fern Canyon, 1996.

Cordingly, David. Under

the Black Flag. Random House, 1995.

Davis, William C. The

Pirates Laffite: The Treacherous World of the

Corsairs of the Gulf. Harcourt, 2005.

Defoe, Daniel. A

General History of the Pyrates. Dover, 1999.

Dunham, Jacob. Journal

of Voyages: Containing an Account of the

Author’s Twice Being Captured by the English

and Once by Gibbs the Pirate . . . .

Published for author, 1850.

Eastman, Tamara J.,

and Constance Bond. The Pirate Trial of Anne

Bonny and Mary Read. Fern Canyon , 2000.

Exquemelin, Alexander.

Buccaneers of America. Dover, 2000.

Gee, Joshua. Narrative

of Joshua Gee of Boston, Massachusetts, While

He was Captive in Algeria of the Barbary

Pirates. Wadsworth Atheneum, 1943.

Gottschalk, Jack A.,

and Brian P. Flanagan. Jolly Roger with an Uzi.

Naval Institute Press, 2000.

Hoffman, Paul E. Spanish

Crown and the Defense of the Caribbean,

1535-1585. LSU Press, 1980.

Konstam, Angus. The

History of Pirates. Lyons Press, 1999.

Lee, Robert E. Blackbeard

the Pirate. John F. Blair, 2002.

Marley, David F. Pirates

and Privateers of the Americas. ABC-CLIO,

1994.

Marx, Jenifer. Pirates

and Privateers of the Caribbean. Krieger,

1992.

Parker, Lucretia. Piratical

Barbarity of the Female Captive. Peter

Pauper Press: 1930.

Rediker, Marcus. Villains

of all Nations: Atlantic Pirates in the Golden

Age. Beacon, 2004.

Rogozinski, Jan. Honor

Among Thieves: Captain Kidd, Henry Every, and

the Pirate Democracy in the Indian Ocean.

Stackpole, 2000.

Rogozinski, Jan. Pirates!

Brigands, Buccaneers and Privateers in Fact,

Fiction, and Legend. Facts on File, 1995.

Smith, Aaron. The

Atrocities of the Pirates. Golden Cockerel,

1929.

Zacks, Richard. The

Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd.

Hyperion, 2002.

Review

Copyright ©2005 Cindy

Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |

One

frequent abuse of power stemmed from the letters of

marque the colonial governors issued.

One

frequent abuse of power stemmed from the letters of

marque the colonial governors issued.

Few

pirates actually married. Out of a sampling of 521,

only twenty-three had wives. Those convicted of

their crimes often asked for their parents’

forgiveness, but rarely mentioned wives and

children. There were exceptions, though. In 1709,

forty-seven women and others kinsmen petitioned

Queen Anne to pardon the pirates of Madagascar.

Few

pirates actually married. Out of a sampling of 521,

only twenty-three had wives. Those convicted of

their crimes often asked for their parents’

forgiveness, but rarely mentioned wives and

children. There were exceptions, though. In 1709,

forty-seven women and others kinsmen petitioned

Queen Anne to pardon the pirates of Madagascar.  After

the golden age of Piracy ended around 1730, the

number of pirates declined dramatically, but hey did

not cease preying on unwary vessels. Significant

losses to merchants and shipowners, as well as

frequent victims’ complaints, spurred the American

and British governments to clamp down on piracy. In

1822, the United States Navy formed a special

squadron to carry out this mission. “The Mosquito

Fleet” established its base on Key West under the

command of Commodore David Porter, and within three

years, pirates ceased to plague maritime commerce in

Caribbean and American waters. Porter, however, was

not the first of the pirate hunters.

After

the golden age of Piracy ended around 1730, the

number of pirates declined dramatically, but hey did

not cease preying on unwary vessels. Significant

losses to merchants and shipowners, as well as

frequent victims’ complaints, spurred the American

and British governments to clamp down on piracy. In

1822, the United States Navy formed a special

squadron to carry out this mission. “The Mosquito

Fleet” established its base on Key West under the

command of Commodore David Porter, and within three

years, pirates ceased to plague maritime commerce in

Caribbean and American waters. Porter, however, was

not the first of the pirate hunters.

.jpg)

As the governor of

Jamaica, Sir Nicholas Lawes presided over the trials

of Calico Jack Rackham (16-17 November 1720) and

Anne Bonny and Mary Read (28 November 1720). Serving

on the court with Lawes were five counselors, a

chief justice, two naval captains, the

receiver-general, the secretary, and the collector.

After explaining how and why Lawes had the right to

assemble the court, the register read the charges

against Bonny and Read. Once the accused pled not

guilty, he called witnesses to prove otherwise.

Although not permitted to be represented by counsel,

the accused could call witnesses on their behalf, or

ask questions of prosecution witnesses. Bonny and

Read opted to do neither. The court deliberated

their fates in the presence of the register, then

reconvened. Lawes pronounced their sentences: “You .

. . are to go from hence to the place from whence

you came, and from thence to the place of execution;

where you shall be severally hanged by the neck till

you are severally dead. And God of his infinite

mercy be merciful to both your souls.” (Cordingly)

As the governor of

Jamaica, Sir Nicholas Lawes presided over the trials

of Calico Jack Rackham (16-17 November 1720) and

Anne Bonny and Mary Read (28 November 1720). Serving

on the court with Lawes were five counselors, a

chief justice, two naval captains, the

receiver-general, the secretary, and the collector.

After explaining how and why Lawes had the right to

assemble the court, the register read the charges

against Bonny and Read. Once the accused pled not

guilty, he called witnesses to prove otherwise.

Although not permitted to be represented by counsel,

the accused could call witnesses on their behalf, or

ask questions of prosecution witnesses. Bonny and

Read opted to do neither. The court deliberated

their fates in the presence of the register, then

reconvened. Lawes pronounced their sentences: “You .

. . are to go from hence to the place from whence

you came, and from thence to the place of execution;

where you shall be severally hanged by the neck till

you are severally dead. And God of his infinite

mercy be merciful to both your souls.” (Cordingly) Another witness against

pirates, one who usually didn’t testify, was the

informer. Some sought revenge for a slight; others

thought it their civic responsibility. Most did it

for a price. Such was the case involving

Another witness against

pirates, one who usually didn’t testify, was the

informer. Some sought revenge for a slight; others

thought it their civic responsibility. Most did it

for a price. Such was the case involving  One thinks

of a minister as preaching to his flock and

comforting the sick, but some clergy added another

task to their duties – extracting confessions from

pirates and persuading them to repent before they

died. The Reverend Paul Lorrain, the Ordinary

(prison chaplain) at

One thinks

of a minister as preaching to his flock and

comforting the sick, but some clergy added another

task to their duties – extracting confessions from

pirates and persuading them to repent before they

died. The Reverend Paul Lorrain, the Ordinary

(prison chaplain) at