Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Pirates &

Religion

by Cindy Vallar

Congress

shall make no law respecting an establishment of

religion, or prohibiting the free exercise

thereof . . . .

The First Amendment of the Constitution guarantees religious freedom for all

people who live in the United States. Inclusion of

this right stems from the fact that the countries

from which our ancestors hailed lacked this freedom.

Each country practiced a state religion and its

citizens were expected to adhere to that faith and

pay that church’s taxes. Initially, most of Europe

was Roman Catholic. During the late fifteenth and

sixteenth centuries, men like Jan Hus and Martin Luther objected to some

Church practices, which led to the Protestant Reformation. Of

course, some citizens preferred to practice faiths

other than the state religion, but they often

encountered persecution because of this.

The intersecting of religion and piracy and/or

privateering took place over many centuries. At

times these men and women championed their faith; at

other times they rejected all parts of the state, of

which religion was one aspect. Pirates of the first

quarter of the eighteenth century fell into this

latter category. They rejected any convention of the

state, including religion, because they saw it as a

way for the state to control and/or oppress the

majority of its citizens. When Samuel Bellamy and his crew

captured Captain Beer’s sloop in 1717, Bellamy

explained:

. . .

there is no arguing with such sniveling Puppies,

who allow Superiors to kick them about Deck at

Pleasure; and pin their Faith upon a Pimp of a

Parson; a Squab, who neither practices nor

believes what he puts upon the chuckle-headed

Fools he preaches to. (Defoe, 587)

Only when faced with

their own deaths at the hangman’s noose did some of

these rogues return to the fold, oftentimes through

the ministry of clergymen who visited them in jail

with the hope of extracting their confessions and to

offer them redemption for their sins and solace

during the final moments of their lives prior to and

during their executions. Perhaps the best known of

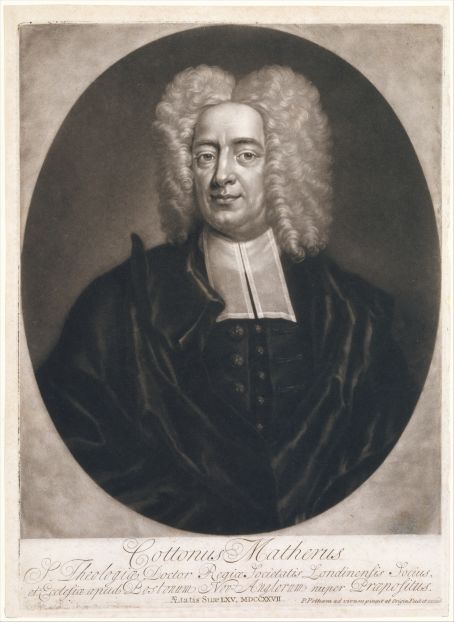

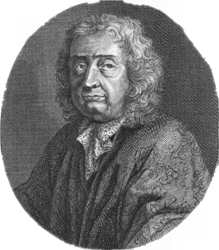

these ministers was the Reverend Cotton Mather, who counseled

men like William Fly, John Phillips, and John Quelch. Another such

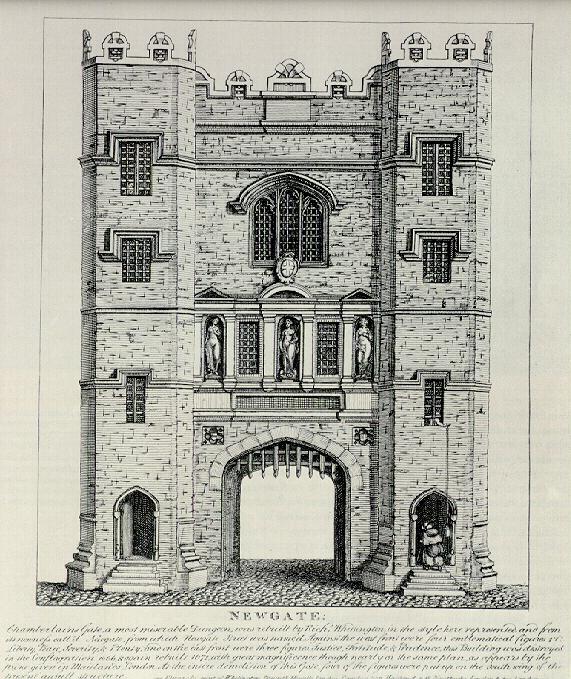

gentleman was the Reverend Paul Lorrain, the Ordinary

(prison chaplain) at Newgate Gaol.

Cottonus Matheris (Cotton

Mather) engraved by Peter Pelham in 1728

(Source: The Met)

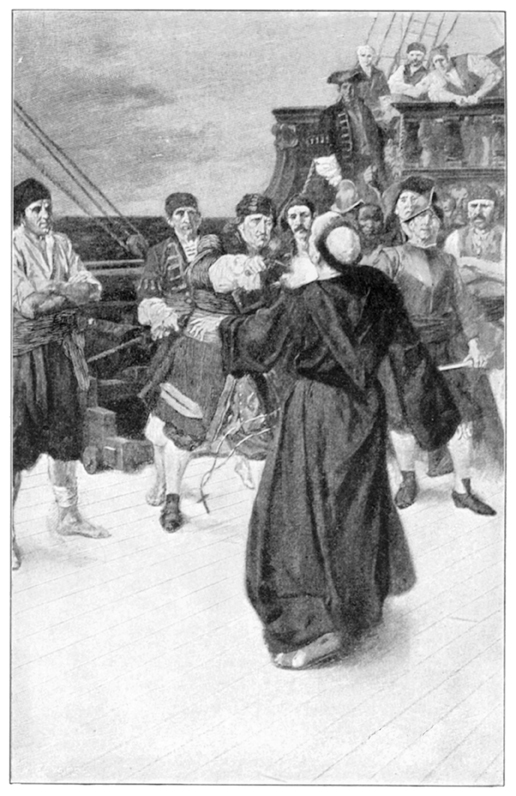

The Pirate's End by George Albert Williams in

1813 (Source: Dover's Pirates)

Old Newgate Prison (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Christopher Scudamore, the cooper in John Quelch’s

crew, was convicted of piracy in Boston in 1704. He

“requested an extra three days to say his prayers

and study the scriptures. At the gallows, he sang

the first part of the 31st Psalm through by

himself.” (Travers, 48)

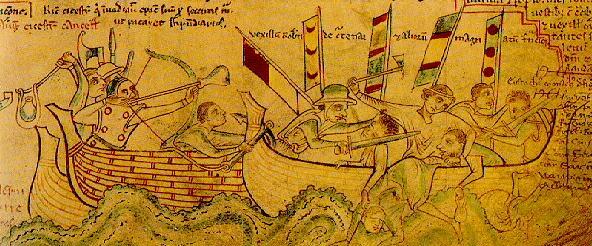

But what of earlier time periods? The Vikings often raided monasteries, but the

primary target was the rich plunder contained within

the walls of these centers, rather than because

their beliefs conflicted with those of the Church.

Symeon of Durham witnessed one such raid.

They came

to the church of Lindisfarne, laid

everything waste with rievous plundering,

trampled the holy places with polluted feet, dug

up the altars and seized all the treasures of

the holy church. They killed some of the

brothers; some they took away with them in

fetters; many they drove out, naked and loaded

with insults; and some they drowned in the sea.

In medieval times,

religion played a crucial role in the Crusades. These holy

wars pitted European Christians against

Muslims of the Ottoman Empire. Both sides employed

corsairs to attack enemy shipping and raid coastal

villages. The Barbary corsairs came from

Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, and Salé along the northern

coast of Africa. Whenever Janissaries, the warriors

on Barbary ships, boarded an enemy vessel, the khodja

(purser) “read out verses from the Koran in a

loud voice”. (Earle, 44) The corsairs’ Christian

counterparts came from religious orders, most

notably the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem

(eventually known as the Knights of Malta) and the

Knights of St. Stephen. Livorno (also known as

Leghorn) was a haven for Christian corsairs who

sailed under the Duke of Tuscany’s flag. Sometimes

their raids crossed that gray line between

privateering and piracy, and both sides attacked

friendly ships rather than just those of their

enemies. According to documents dated 6 June and 11

June 1607, in the Venetian Calendar of State Papers,

the duke “receives, shelters and caresses the worst

of the English men who are proclaimed pirates by the

King.”

Viking,

Knights of St John of Jerusalem, and Barbary

Corsair

Aside from the religious element of these wars,

trade and politics also played important roles. Both

sides sought not only wealth but also slaves. Jewish merchants

played key roles in brokering sales of the captured

men, women, and cargoes the corsairs on either side

plundered. Redemptionist orders of Catholic priests

assisted in negotiations with the rulers of the

Barbary States to repatriate these captured people

to their homelands. Other captives “turned Turk”

(converted from Christianity to Islam) to escape

slavery and gain wealth and prestige through

plundering. Following the defeat of the Ottoman navy

at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571,

both Christian and Muslim privateers eventually

devolved into pirates. Corsairs of the Knights of

Malta continued to plunder Mediterranean trade until

Napoleon landed on the island

in 1798. The Barbary corsairs continued to plunder

vessels into the first half of the nineteenth

century.

Andries van Eertvelt's 1640 oil

painting of The Battle of Lepanto (1571)

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Death of Eustace the Monk

during the Battle of Eustace by Matthew Paris,

1217

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Pope Alexander VI divided the

New World between Spain and Portugal in the Treaty

of Tordesillas in 1494. This didn’t sit well with

other European countries, especially after Jean

Fleury (or Florin), a French privateer, captured

three Spanish vessels in 1523 laden with

chests

filled with Aztec gold, sparkling jewelry, and

religious statues; precious jewels, including an

emerald the size of a man’s fist; even a live

jaguar in a cage. In all, the plunder was valued

at more than 800,000 gold ducats – the

equivalent of a staggering 234 million dollars

today. (Konstam, World, 66)

This “find” confirmed

rumors of the riches of the New World, which enticed

the English, Dutch, and French to stake their claims

on lands in the Caribbean and North and South

America. During the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries, these interlopers sailed as privateers or

pirates, depending on whether the countries for

which they sailed were at war or not with Spain.

Raids on Spanish vessels and holdings in the

Caribbean became particularly prevalent from 1568 to

1603. While the primary goal of these pirates and

privateers remained financial gain with minimal

effort, religious zealotry also played a vital role

in the attacks. English Sea Dogs, Dutch Sea Beggars, and French Huguenots championed

the Protestant faiths against Spain, defender of

Catholicism. One of the best known of the Sea Dogs

was Sir Francis Drake, Queen

Elizabeth I’s “pirate.”

[He] would

have learned that salvation is a matter of

absolute faith in God, and that his actions

should stem from his faith. He would also have

learned to despise the Catholic Church, its

grasping, materialistic ways made visible in the

fine altars of its cathedrals and the rich

vestments of its clergy even as it ignored the

poverty and anguish of the common man. (Dudley,

17)

Born around 1540, he

lived in a Protestant England ruled by Henry VIII (1509-1547) and Edward VI (1547-1553). When Mary I ascended the throne on

the death of her brother, Catholicism became the

true religion of England once again and Protestants

paid the price. During her reign, she sent many

“heretics” to fiery deaths, which earned her the

nickname, Bloody Mary. Her younger sister, Elizabeth,

returned England to the Protestant faith of her

father, and Drake was one of many privateers who

zealously protected “God, Queen, and Country.” Born around 1540, he

lived in a Protestant England ruled by Henry VIII (1509-1547) and Edward VI (1547-1553). When Mary I ascended the throne on

the death of her brother, Catholicism became the

true religion of England once again and Protestants

paid the price. During her reign, she sent many

“heretics” to fiery deaths, which earned her the

nickname, Bloody Mary. Her younger sister, Elizabeth,

returned England to the Protestant faith of her

father, and Drake was one of many privateers who

zealously protected “God, Queen, and Country.”

In 1573, he and his men captured a mule train laden

with more than fifteen tons of silver from Peruvian

mines. Lacking the means to carry this haul back to

the ships, he buried all but a few chests of gold

that held 50,000 pieces of eight (valued at

$6,000,000 in 2012). Four years later, Drake set off

on a journey that took him around the world. A

primary objective for this voyage was to plunder

Spanish treasure on land and at sea. He attacked

Valparaiso (Chile) where his men “desecrated a

little chapel, stealing what they gleefully thought

of as the superstitious paraphernalia it was

decorated with.” (Coote, 147) His biggest prize was

the Nuestra de la Concepción, an unarmed

treasure galleon, which he captured in 1579.

She carried

coin

chests filled with silver, gold bars, and over

26 tons of silver ingots. The total haul was

estimated at 400,000 pieces-of-eight – the

equivalent of $53 million today. At the time it

represented about half of England’s annual

income . . . (Konstam, World, 80)

While a hero in his own

country, Drake was anything but to his victims. They

considered him a “heretic and pirate,” and the

Spaniards made no distinction between piracy and

privateering. In 1579, one of his men

horrified their Spanish captives when he smashed a

crucifix on a their ship before sending it into the

ocean. While at Guatalco, he forced his prisoners,

including a priest, to participate in a Protestant

service. Eight years later, Thomas Cavendish desecrated

the town’s church.

In April 1576, John Oxenham set out on a

trading voyage, but by February of the following

year, he had turned to piracy. In September, he and

his men attacked the Pearl Islands off the coast of

Panama. According to Spanish reports, there was “a

furious outbreak of iconoclastic violence, with the

destruction of images and crucifixes, and the public

assault and humiliation of a friar, who was forced

to wear a chamber pot on his head.” A later report

cited the “castration of two Franciscan friars.”

(Appleby, 133) This and other incidents, whether

actual or rumor, led Spaniards to take drastic

measures after capturing pirates. They eventually

captured and executed Oxenham in Lima in November

1580.

Many of the French buccaneers were Huguenots,

Protestants who were persecuted in their homeland

and had fled to the Caribbean. Since Spain was the

defender of the Catholic Church, the religion that

had persecuted them, these men waged private wars

against their enemy. One city these pirates sacked

was Nombre de Dios in 1537. Four years later, they

looted Margarita pearl farms. François le Clerc (also known

as Jambe de Bois or Peg Leg) attacked villages along

the coasts of Puerto Rico and Hispaniola. In 1554,

he sacked Santiago de Cuba. One of his captains,

Jacques de Sores, remained in the Caribbean after le

Clerc returned to France. Sores laid siege to Havana

in July 1555, eventually capturing it, plundering

the houses and desecrating churches, then torching

the city. When he captured a ship off the Canary

Islands in 1570, he tossed forty Jesuits overboard,

whether they were alive or dead. He also jettisoned

any holy images, bibles, and relics he found about

the Portuguese vessel.

In the early decades of the next century, Diego the Mulatto sailed with

Cornelius Corneliszoon Jol

(also known as Piede Palo or Wooden Leg) and Pierre le Grand. In 1637,

Diego captured Thomas Gage, a Catholic priest from

England, on his way to Havana. Since Diego’s mother

resided there, he invited Gage to dinner and asked

him “to remember him to her, and how that for her

sake he had used well and courteously in what he

did.” He also recited a Spanish proverb: Hoy por

me, mañana for ti – Today for me, tomorrow for

you. (Little, How, 81)

Jean le Vasseur, who oversaw Tortuga, a haven for the

buccaneers, was a French Protestant with a great

hatred for all things Catholic. When Spaniards fell

into his hands, they “were likely to find themselves

subjected to an Inquisition-like torture in one of

his dungeons or cages (one of which he called

‘Purgatory’).” (Lane, 100) Although his primary

motives for such treatment involved financial gain,

perhaps religion played a small role in why he

subjected these prisoners to such vile treatment.

In contrast, when Bertrand d’Ogeron became governor

of Tortgua in 1665, he arranged

for two priests to accompany a boatload of French

maidens from France because he wanted the buccaneers

to settle down. When the women came ashore, each

buccaneer introduced himself and selected a willing

woman. The priests then sanctified their union.

Laurens Prins, a Dutch corsair

who sailed the Caribbean and South Sea, was more

akin to le Vasseur in his treatment of Catholic

clerics. In 1670, he attacked Granada prior to

joining Henry Morgan on his voyage to sack Panama.

After seizing control of Granada, Prins demanded a

ransom of 70,000 pesos. “[H]e made havoc and a

thousand destructions, sending the head of a priest

in a basket and saying that he would deal with the

rest of the prisoners in the same way,” according to

a Spanish account. (Earle, 151)

The buccaneers often used Petit Goave as a safe haven.

The first church was built there in 1670. In 1685, two Capuchin monks ministered to

the Catholic residents. Few firsthand accounts,

written either by the buccaneers themselves or their

contemporaries, rarely mention how English

buccaneers worshipped, but Basil Ringrose cited two

instances in his journal. A comrade of William Dampier and Lionel Wafer, he wrote on 9

January 1681:

This day

was the first Sunday that ever we kept by

command and common consent since the loss and

death of our valiant commander, Captain Sawkins.

This generous-spirited man threw the dice

overboard, finding them in use on the said day.

(Esquemeling, 398)

Although

French and English buccaneers formed alliances

against Spanish towns and villages in the New World,

religious differences sometimes caused problems. On

one such expedition, Raveneau de Lussan, a flibustier

and chronicler, noted that although the English

pirates might observe the Sabbath and sing Psalms,

they had Although

French and English buccaneers formed alliances

against Spanish towns and villages in the New World,

religious differences sometimes caused problems. On

one such expedition, Raveneau de Lussan, a flibustier

and chronicler, noted that although the English

pirates might observe the Sabbath and sing Psalms,

they had

absolutely

no scruples, when entering churches, against

knocking down crucifixes with their sabres,

firing guns and pistols, and breaking and

mutilating the images of saints with their arms,

scoffing at the veneration in which Frenchmen

hold them. (Little, Buccaneer’s,

108)

In contrast, after de

Lussan and his fellow flibustiers captured

Granada, they marched to the cathedral and

celebrated with a Te Deum. They also

preferred to ask “God ardently for victory and

silver” before any plundering endeavor. (Little, Buccaneer’s,

108)

Jean-Baptiste Labat, a

Dominican priest who went to the Caribbean to

replace one of the missionaries who had died during

an epidemic, arrived in Martinique in 1694. In March

of that year, he presided over mass at the behest of

a flibustier captain and crew in the harbor

of Saint-Pierre. He claimed that rather than

desecrating Catholic relics, they “fired salvoes at

appropriate points during his ceremony and a portion

of their booty was donated to the Church.” (Marley,

672) Jean-Baptiste Labat, a

Dominican priest who went to the Caribbean to

replace one of the missionaries who had died during

an epidemic, arrived in Martinique in 1694. In March

of that year, he presided over mass at the behest of

a flibustier captain and crew in the harbor

of Saint-Pierre. He claimed that rather than

desecrating Catholic relics, they “fired salvoes at

appropriate points during his ceremony and a portion

of their booty was donated to the Church.” (Marley,

672)

While

Catholic buccaneers might treat those who had taken

holy vows kindly, Ringrose wrote of one instance

when his fellow English buccaneers did not. While

Catholic buccaneers might treat those who had taken

holy vows kindly, Ringrose wrote of one instance

when his fellow English buccaneers did not.

That day

we cried out all our pillage, and found that it

amounted to 3,276 pieces-of-eight, which was

accordingly divided by shares amongst us. We

also punished a friar, who was chaplain to the

bark aforementioned, and shot him upon the deck,

casting him overboard before he was dead.

(Esquemeling, 360)

Ringrose didn’t agree

with this type of cruelty, but his opinion wasn’t

strong enough to sway his comrades.

Alexandre Exquemelin, a pirate

surgeon who wrote The

Buccaneers of America, “reported that rovers

prayed before eating – filibusters recited the Canticle of Zachariah, the Magnificat, and the Miserere, while the ‘pretended

reformers’ (Huguenots, or most of the

English and Dutch) read a chapter from the Bible and

recited Psalms.” Such practices pertained only to

the 1660s, because later periods of buccaneering

make no mention of “formal religious practice.”

(Little, Buccaneer’s, 108)

In the final decade of the seventeenth century, some

pirates forsook the Caribbean and headed for the

Indian Ocean to plunder ships carrying Muslims on

their annual pilgrimage to Mecca. Darby Mullins was

one of the few men who remained loyal to William Kidd and hanged with

him in 1701. When he confessed to Ordinary Lorrain,

prior to his death, this Irishman revealed “that he

didn’t know that it was unlawful to plunder the

ships of Moslems.” (Zacks, 386) Philip Gosse, a

pirate historian, paraphrased Mullins’ words more

succinctly:

. . . he

went to New York, where he met Captain Kidd, and

was, according to his own story, persuaded to

engage in piracy, it being urged that the

robbing only of infidels, the enemies of

Christianity, was an act, not only unlawful, but

one highly meritorious. (Gosse, 229)

When these ships returned

to India, they carried vast amounts of silk, jewels,

silver and gold. The greatest haul came in 1695 when

Henry Every and his men captured Gang-i-Sawai,

whose plundered treasure has been valued in excess

of $1,000,000.

Captain Avery takes the Great

Moghul's Ship by unknown artist

Close-up of Woodes Rogers in William

Hogarth's painting of the governor and his

family

(Sources: Dover's Pirates and Wikimedia Commons)

In 1709, Woodes Rogers sailed around

the world on a privateering cruise. After rounding

Cape Horn, he put in at Juan Fernandez Island where

he found Alexander Selkirk. The privateer from

William Dampier’s expedition had been marooned on

the island for four and a half years. In his journal

Rogers wrote:

[he]

employ’d himself in reading, singing Psalms, and

praying; so that he said he was a better

Christian while in this Solitude than ever he

was before, or than, he was afraid, he should

ever be again. (Rogers, 72)

Years later, while

attempting to persuade the pirates of New Providence to

accept the king’s pardon and retire from plundering,

Rogers included literature from the Society of the Promotion of

Christian Knowledge as part of his arsenal. It

probably wasn’t a particularly successful technique,

but knowing the pirates easily outnumbered him, he

could ill afford not to try any means necessary to

achieve his goal.

Darby Mullins wasn’t the only one who thought there

was nothing wrong with attacking non-Christian

ships. In 1719, Turner Stevens, a gunner aboard

George Shelvocke’s privateer Speedwell, suggested

they sail for the Red Sea, rather than Spanish

waters, because “there could be no harm in robbing

the Mahometans, whereas the Spaniards were good

Christians, whom it was a sin to injure.”

(Shelvocke, 34) Shelvocke, however, heeded his

letter of marque and attacked Spanish towns and

vessels. Oftentimes when pirates failed to receive

their ransoms, they torched the towns without caring

what burned. When Shelvocke captured Payta in 1720,

he didn’t want to burn the churches, but he did

order his men to set fire to several houses in the

town.

. . . the

governor was determined not to ransom the town,

and did not care what became of it, provided the

churches were not burnt. Though I never had any

intention to destroy any place devoted to divine

worship, I answered that I should have no regard

to the churches, or anything else, when I set

the town on fire. . . . This seemed to make a

great impression, and he promised to return in

three hours with the money. (Shelvocke, 92)

Whereas English pirates

of the previous century observed the Sabbath and

sang Psalms, not so the pirates who followed Howell Davis. Captain William Snelgrave made their

acquaintance in 1718 when they took his ship off

Sierra Leone.

The

execrable oaths and blasphemies I heard among

the ship’s company, shocked me to such a degree,

that in Hell its self I thought there could not

be worse; for though many seafaring men are

given to swearing and taking God’s name in vain,

yet I could not have imagined human nature could

ever so far degenerate, as to talk in the manner

those abandoned Wretches did. (Konstam and

Rickman, 36)

Nor were some pirates

inclined to treat priests as the French corsairs of

Martinique had done several decades earlier. Edward Low, not known for his

kind treatment of prisoners (especially those

audacious enough to fight back), reserved a special

punishment for two friars taken in 1722 when he

captured the galley Wright.

. . .

because at first they shewed Inclinations to

defend themselves and what they had, the Pyrates

cut and mangled them in a barbarous Manner;

particularly some Portuguese Passengers, two of

which being Friers, they triced up at each Arm

of the Fore-Yard, but let them down again before

they were quite dead, and this they repeated

several Times out of Sport. (Defoe, 324)

In June of that year, Philip Ashton became another

captive of Ned Low’s. In his memoir of his time with

the pirates, he frequently attributed the saving of

his life to God’s intervention. He also noted that

“every thing that had the least face of Religion and

Virtue was entirely banished.” (Rediker, Between,

176)

What of

pirates in other parts of the world? Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a

French traveler, recounted a tale involving

Malabaris, pirates who preyed in Indian waters. They

were Muslims with little tolerance for Christians. What of

pirates in other parts of the world? Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a

French traveler, recounted a tale involving

Malabaris, pirates who preyed in Indian waters. They

were Muslims with little tolerance for Christians.

I have

seen a Barefoot Carmelite Father who had been

captured by these pirates. In order to obtain

his ransom speedily, they tortured him to such

an extent that his right arm became half as

short as the other, and it was the same with one

leg. (Little, Pirate, 240)

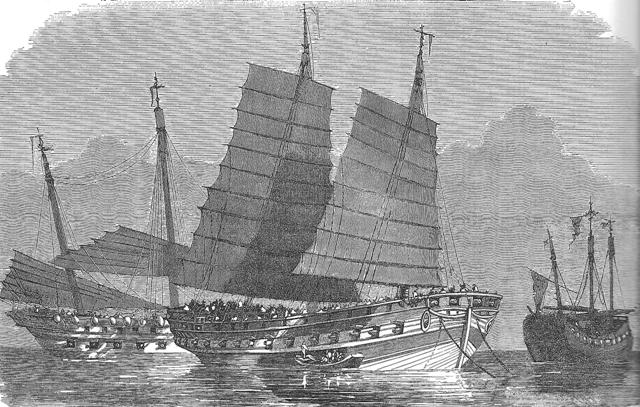

Unlike their western

counterparts, Chinese pirates never became enmeshed

in religious conflicts. They prayed to dieties,

called Joss, before sailing.

Zhang Bao, who was Zheng Yi Sao’s lover and

husband after the death of his adopted father, had a

temple constructed aboard his flagship. He and his

men gathered before each venture and burned incense

and sought signs that each would succeed. They

frequently visited temples whenever they were ashore

and donated to the priests who tended the temples.

The pirates frequently stopped at the Hui-chou’s

temple, made famous because its deity was noted for

miracles. Legend says several pirates decided to

take the idol with them, but were unable to remove

it from the pedestal upon which it sat. At least not

until Zhang Bao touched it. Once he did, they had no

problem transporting it to their junks.

Chinese war junks in 1857

(Source: Dover's Nautical Illustrations)

Although the gods frequently indicated Zhang Bao’s

plans would succeed, every once in awhile, they did

not. On one occasion, his junk anchored near four

guardhouses made out of mud where he waited for two

days. One the third, the forts defending the town

fired on him, but he never returned fire because the

Joss indicated he would fail in this

endeavor. At another time in 1809, he lost 300 men

in an attack. So he consulted the Joss,

which recommended he retreat. The day after Zhang

Bao ceased the attack, strong winds permitted his

men to break through the blockade and sail away.

In 1858, Fanny Loviot published an account of her capture by and

time with Chinese pirates near Hong Kong. In this

book she described their evening prayer ceremony.

Every junk

. . . is furnished with an altar. On this altar

they burn small wax-lights, and offer up

oblations of meat and drink. They pray every

night at the same hour, and begin with a hideous

overture played upon gongs, cymbals, and drums

covered with serpent skins.

First of all, I

saw a young Chinese come forward with two

swords, which he stuck upright in the very

centre of the deck. Beside these he then placed

some saucers, a vase filled with liquid, and a

bundle of spills, made of yellow paper, and

intended for burning. A lighted lantern was next

suspended to one of the masts, and the chief

fell upon his knees before the shrine.

After chanting for some time, he took up the

vase and rank; and next proceeded, with many

gesticulations, to chink a lot of coins and

medals together in his hands. The paper spills

were then lighted and carried round and round

the swords, as if to consecrate them. These

ceremonies completed, the captain rose from his

knees, came down to the after-part of the junk,

waved the burning papers to and fro, and threw

them solemnly into the sea. The gongs and drums

were now played more loudly, and the chief

seemed to pray more earnestly than ever; but as

soon as the last paper was dropped, and the last

spark extinguished, the music ceased, the prayer

came to an end, and the service was over.

Altogether it had taken quite twenty minutes . .

. . (Loviot, 110-111)

After reading these

examples, one soon comes to the conclusion that not

all pirates forsook their beliefs in a higher power.

Some were immoral. Others zealously championed their

faiths. Still others strayed from a righteous path

until faced with death. To depict all pirates as

godless men contradicts reality. It is also

inaccurate to say that regardless of the time period

religion has little to do with piracy. Before these

men (and women) go on the account, religion plays an

important role in their daily lives. Just because

they become pirates doesn’t negate its impact on

them. William Fly, who stands trial

for piracy in 1726, has several conversations with

the Reverend Cotton Mather, who wishes for Fly to

confess his sins. Mather wants Fly to forgive the

man who betrays him and equates malice against

someone as being as great a sin as lying. Fly

indicates that to forgive will be wrong: “I won’t dy

with a Lye in my mouth.” (Mather, 16) As Emily

Collins points out in her senior thesis on religion

and piracy in the eighteenth century, sometimes a

pirate does believe but perhaps not according to the

tenets of a particular religion:

Fly

continued to illustrate his piety when he stated

that he read The Converted Sinners book, about

piety, before he was brought in and convicted .

. . . At the same time he stated this, Fly was

holding the Bible in his hands. Even though Fly

never confessed to being a pirate or repented

his sins before his final hour, it is quite

apparent through his dialogue that he was a man

who did have knowledge and respect of religion.

(Collins, 8)

For additional information, please see:

Antony,

Robert J. Pirates in the Age of Sail. W.

W. Norton, 2007.

Appleby, John C. Under

the Bloody Flag. The History Press, 2009.

Bromley, J. S.

“Outlaws at Sea, 1660-1720: Liberty, Equality, and

Fraternity among the Caribbean Freebooters” in Bandits

at Sea edited by C. R. Pennell. New York

University, 2001.

Collins, Emily E. Eyes

on God and Gold: The Importance of Religion

during the Golden Age of Caribbean Piracy.

[unpublished thesis] University of North Carolina,

2004.

Coote, Stephen. Drake.

Thomas Dunne, 2003.

Cordingly, David. Under

the Black Flag. Random House, 1995.

Defoe, Daniel. A

General History of the Pyrates. Dover, 1999.

Dudley, William G. Drake:

For God, Queen, and Plunder. Brassey’s,

2003.

Earle, Peter. The

Pirate Wars. Thomas Dunne, 2003.

Esquemeling, John. The

Buccaneers of America. Rio Grande Press,

1992.

Gosse, Philip.

The Pirates’ Who’s Who. Rio Grande Press,

1924.

Greene, Molly. Catholic

Pirates and Greek Merchants. Princeton,

2010.

Kinkor, Kenneth

J. “Black Men under the Black Flag” in Bandits

at Sea edited by C. R. Pennell. New York

University, 2001.

Konstam, Angus. Piracy:

The Complete History. Osprey, 2008.

Konstam, Angus. The

World Atlas of Pirates. Lyons Press, 2009.

Konstam, Angus, and

David Rickman. Pirate: The Golden Age.

Osprey, 2011.

Lane, Kris E. Pillaging

the Empire. M. E. Sharpe, 1998.

Little, Benerson. The

Buccaneer’s Realm. Potomac, 2007.

Little, Benerson. How

History’s Greatest Pirates Pillaged, Plundered,

and Got Away with It. Fair Winds Press,

2011.

Little, Benerson. Pirate

Hunting. Potomac, 2010.

Loviot, Fanny. A

Lady’s Captivity among Chinese Pirates.

National Maritime Museum, 2008.

Magnus Magnusson. Vikings!

E.P. Dutton, 1980.

Marley, David F. Pirates

of the Americas. ABC-CLIO, 2010.

Mather, Cotton. The

Vial Poured Out Upon the Sea . . . .

Boston, 1726.

Murray, Dian H. Pirates

of the South China Coast 1790-1810.

Stanford, 1987.

Rediker, Marcus. Between

the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea. Cambridge,

1999.

Rediker, Marcus. Villains

of All Nations. Beacon Press, 2004.

Rogers, Woodes. A

Cruising Voyage Round the World. Narrative

Press, 2004.

Rose, Jamaica, and

Captain Michael MacLeod. The Book of Pirates.

Gibbs Smith, 2010.

Sanders, Richard. If a

Pirate I Must Be . . . . Skyhorse, 2007.

Shelvocke, George. A

Privateer’s Voyage Round the World.

Seaforth, 2010.

Thomas, Graham A. Pirate

Hunter. Pen & Sword, 2009.

Weiss, Gillian. Captives

and Corsairs. Stanford, 2011.

Zacks, Richard. The

Pirate Hunter. Hyperion, 2002.

Copyright ©

2012 by Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |