The History of Maritime Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor & Reviewer

P.

O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Cindy Vallar, Editor & Reviewer

P.

O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

|

|

|

|

|

|

í

víking

Norse

who went plundering

By

Cindy Vallar

In this year dire portents appeared over Northumbria and sorely frightened the inhabitants. They consisted of immense whirlwinds and flashes of lightning, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the air. A great famine followed soon upon these signs, and a little after that in the same year on the ides of June the harrying heathen destroyed God's church on Lindisfarne by rapine and slaughter. -- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 793Simon of Durham witnessed this attack on the monastery at Lindisfarne, the earliest recorded Norse raid. "They came to the church of Lindisfarne, laid everything waste with rievous plundering, trampled the holy places with polluted feet, dug up the altars and seized all the treasures of the holy church. They killed some of the brothers; some they took away with them in fetters; many they drove out, naked and loaded with insults; and some they drowned in the sea."

When the news reached Charlemagne's court, Alcuin of York--a noted cleric--quoted a warning from Jeremiah (Chapter 1: Verse 14). "Then the Lord said unto me, Out of the North an evil shall break forth upon all the inhabitants of the land." Alcuin and others believed God sent the viking pirates as divine instruments of retribution for Christians' sins.

Raids were commonplace among the Norse. They outfitted ships, plundered towns and monasteries, and sought adventure. Although they pursued far more peaceful pursuits much of the time, the summers saw them go í víking, plundering. Among the treasures sought were the jeweled covers of illuminated manuscripts, gold crucifixes, and silver chalices. Monasteries were particular favorites because of their remoteness, nearness to water, and artisans. When they took captives, the pirates either held them for ransom or sold them into slavery.

Norse pirates first raided Iona, an island off the west coast of Scotland, in 795. They came again in 802 and 806, a raid that ended with the slaying of sixty-eight monks and laymen. Walafrid Strabo, the abbot of Reichenau (Germany), wrote a detailed account of an Irish warrior and aristocrat who pledged his life to God. Somehow Blathmac knew the pirates would raid the monastery in 825 and told those not of stout heart to flee. The next morning the Norse slayed all those who remained except Blathmac. If he told them where Columba's shrine was, they would spare his life. He refused and they tore him limb from limb.

The Orkneyinga Saga mentions numerous Northmen who plundered Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. One was the grandson of Malcolm, King of Scots. Earl Thorfinn began his raids at the age of fifteen, and became noted for his courage and tactical abilities. Tall, strong, and ugly, he craved fame. He often raided with his nephew, Rognvald.

Perhaps the most noted of the Orkney raiders was Svein Asleifarson. After his five ships raided the Hebrides, he headed for Dublin. Along the way he captured two merchant ships laden with broadcloth. Upon his return to Orkney, Svein made awnings from the broadcloth and stitched it to his sails to give the appearance that they were made of fine fabric. Doing so earned the raid the name "the broadcloth viking trip.'"

On his last raid, he left Orkney with seven longships. Finding little plunder in the Hebrides, Svein and his men plundered settlements along the coast of Ireland until they reached Dublin. They took the town before the people even knew the pirates were there. The Dubliners offered to pay Svein whatever he wanted, but only the next day. During the night, they dug deep pits in strategic places, then camouflaged them with branches and straw. In the morning, when Svein and his men came to collect, the Dubliners positioned themselves so that the Norse fell into the pits where they were slain.

The British Isles weren't the only hunting grounds for Norse pirates. Around 860 Ermentarius of Noirmoutier recapped what had occurred in the Frankish Empire. "The number of ships grows: the endless stream of Vikings never ceases to increase. Everywhere the Christians are the victims of massacres, burnings, plunderings. The Vikings conquer all in their path and nothing resists them: they seize Bordeaux, Perigeux, Limoges, Angoulęme, and Toulouse. Angers, Tours, and Orléans are annihilated and an innumberable fleet sails up the Seine and the evil grows in the whole region. Rouen is laid waste, plundered and burned: Paris, Beauvais, and Meaux taken, Melun's strong fortress leveled to the ground, Chartres occupied, Evreaux and Bayeux plundered, and every town besieged." By the end of the ninth century, the Franks had paid the equivalent of twelve tons of silver, grain, livestock, produce, wine, cider, and horses to prevent plundering of their cities and monasteries.

Dudo of Saint Quentin, a Norman who lived in the eleventh century, described one Norse pirate as "cruel, harsh, destructive, troublesome, wild, ferocious, lustful, lawless, death-dealing, arrogant, ungodly and much else besides." Hastein, who lived two centuries before Dudo, raided in the Mediterranean from 859 to 867. He attacked cities in Spain, Morocco, France, and Italy. One goal was to strike Rome. When his men came to the city's gates, they pretended that Hastein had died and asked to give him a Christian burial. The townspeople agreed and watched the procession of Norsemen follow Hastein's coffin to the cemetery. At that point Hastein jumped from his coffin, slew the bishop, and sacked the city. It wasn't until later that Hastein learned he was in Luna, not Rome. Angered, the pirates slew all the men of the city.

Norse pirates comprised the initial phase of the Viking Age, which lasted about three years. Once they established winter bases on distant shores, they settled with their families in places like Jorvik (York), Iceland, Novgorod, and Normandy. Raiding gave way to trade and exploration until the Norse world reached from Russia to North America.

Q and A

From where does the word 'viking' come?

No one knows for sure. The most accepted derivation is from the Norse word vik, which means a creek, bay, or fjord, because pirates lurked in sheltered waters.While we often refer to them as Vikings, their contemporaries did not. The Anglo-Saxons called them "Danes." The Franks referred to them as "Northmen," while the Germans used "Ashmen." Although the Irish often distinguished between whether the pirates had fair hair or dark, all were considered Gaill or "foreigners." The Spanish had a simpler name for them -- Heathens. Slavs and Arabs called them "Rus," from which Russia got its name. The pirates, themselves, distinguished one from the other by the region from which they hailed.

Most Scandinavian peoples, however, were not pirates. They were farmers, merchants, and craftsmen.

Why did they go í víking, plundering?

To accumulate wealth. Gold and silver were far easier to procure through raids on undefended monasteries than through trade. They attacked and left with such speed that few victims could mount a counterattack before the pirates sailed for home. "In those days, trade and piracy went hand in hand…this was an age when everyone was his own master, when the power of the state was unknown and unchallenged…" (Eric Graf Oxensteirna, The World of the Norsemen, 1967)

What did viking pirates wear?

Most wore trousers, long-sleeve shirts, and belted tunics. If they wore cloaks, brooches pinned them to right shoulders to allow access to their weapons. Some wore helmets, but most went bareheaded.Many didn't own shirts of chainmail. Instead they wore padded leather armour. Most Norse, however, simply deflected injurious blows with their shields.

What weapons did they use?

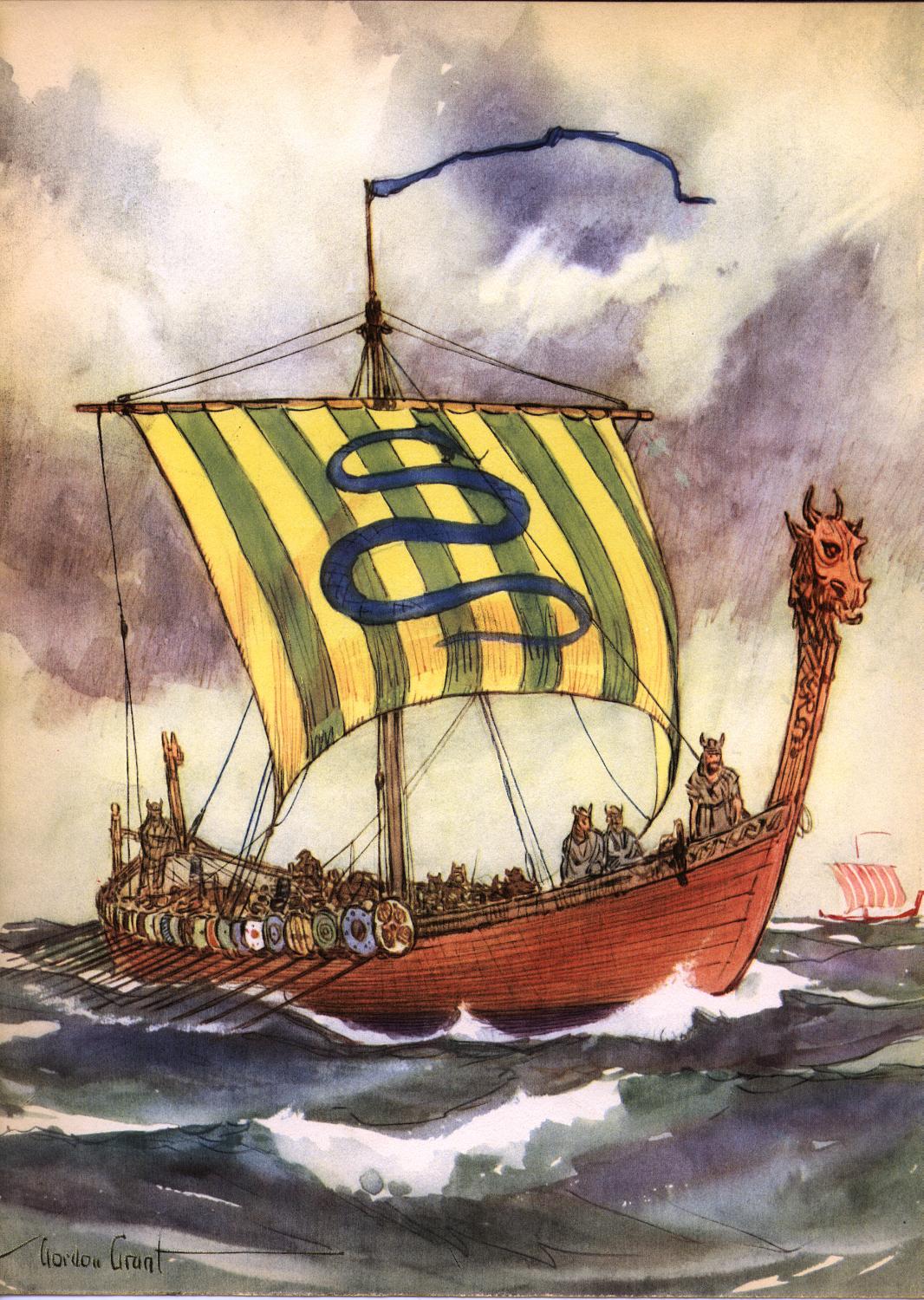

Their deadliest weapon was the double-edged, lightweight sword, measuring almost thirty-six inches in length. This prized possession often had a name like Flame of Battle, Foot Biter, Gnawer, or Hole Maker. Since few could afford such expensive weapons, they used spears and short swords. Some favored broad axes that possessed names of the Valkyrie or female giants. They often carried round wooden shields with a centered metal boss on one side and a leather handgrip on the other.Perhaps the most powerful weapon, though, was the longship. This low vessel had a sleek design that allowed quick and easy navigation across the sea. It was light enough for the raiders to either land on the beach or carry over their heads with ease. The single rudder, affixed to one side of the vessel, steered the longship while a single mast supported the square sail that allowed the ship to skim across the waves when the wind blew. When it didn't, the pirates propelled the vessel with oars. The shallow keels allowed them to go where no one else dared.

Expert navigators, the pirates planned their attacks in advance and usually succeeded in surprising their prey. No one else had ships as fast as theirs. Speed and mobility were the key elements of a Norse raid, which made them difficult to prevent.

How accurate were the holy scribes in their depictions of Norse pirates?

While pillage was the norm when people fought one another, viking pirates violated a sacrosanct rule. They dared to attack sacred places. This coupled with the fact that the Norse weren't Christians make such accounts suspect.Norse pirates didn't attack monasteries because they didn't believe in God. They attacked them because monasteries possessed a prime source of precious metals and gems that adorned holy books and reliquaries, all of which were portable treasures. These pirates employed a favored tactic of pirates of all ages--fear and intimidation. The more terrified the prey, the less likely they resisted.

Without writings such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles or the Annals of Ulster, we would know little about the Viking Age because the Norse didn't have a written language. They preferred to recount their deeds orally. These sagas weren't recorded until many years later and have a biased slant because the poet's intent was to glorify the participants and instruct the listeners.

How did the Norse impact history?

Although the Viking Age lasted only about three hundred years, the Norse left their mark wherever they went. Many place names, particularly in the British Isles, have Norse origins. The Norse destroyed the existing powers in the British Isles, which eventually led to the establishment of the separate nations of Scotland and England. They established the first towns in Ireland. They accelerated the demise of the Carolingians and established the seeds upon which the Normans gained power. They settled Iceland and were among the first to reach Greenland and North America.Did Norse women become pirates?

Perhaps, but there are no historical facts to prove they did. Nanna Damsholt, a historian who studies medieval Danish women--cautions that "People in the Middle Ages did not distinguish as we do between myth and history."Saxo Grammaticus included the tale of Alwilda (aka Alfhild, Alvilda)--who dressed in male attire and became a pirate rather than marry the King of Denmark's son--in his history of the Danes. Only after Prince Alf captured her did he learn that the infamous pirate was his intended and they wed aboard his ship. There remains some question as to whether Alwida was a viking pirate or whether she lived before the Viking Age and many historians believe her tale is a myth.

Henri Musnik, author of Les Femmes Pirates (1930s), mentioned Sigrid the Superb in his book, but failed to cite his sources. Other women included among viking pirates are the Princesses Sela and Rusla of Norway and the Norwegian sisters Russila and Stikla.

© 2003 Cindy Vallar

Home Pirate Articles Pirate Links Book Reviews Thistles & Pirates