Pirates and Privateers Pirates and Privateers

The History of Maritime

Piracy

Cindy Vallar, Editor

& Reviewer

P.O. Box 425,

Keller, TX 76244-0425

Books for Adults ~ Historical

Fiction: Pirates & Privateers

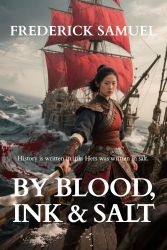

By Blood, Ink & Salt

by Frederick Samuel

Independently Published, 2025, ISBN 9798292440642, US

$17.99

Available in various formats

This is not a biography. It

is the hush between waves – and what

rises when you listen.

Thus begins Samuel’s story of Shek Ying

(also known as Zheng Yi Sao). This is not

a normal rendering of historical fiction.

It is lyrical. With well-chosen words and

phrases, Samuel instills in readers a

sense of place – of China, of sea, of

Asian piracy instead of Western. He

captures the essence of the woman and the

formidable confederation she devises. At

its core is the Code.

Shek Ying does not begin life as a pirate.

She pleasures men, one of whom is a

successful captain of sea bandits. Zheng

Yi wants her join him. She agrees because

she will longer walk in someone’s shadow.

She will be his equal.

Each band has its own leader, but they

sometimes work in consort. Zheng Yi

commands the Red Fleet. Shek Ying sees

potential, and devises principles that, if

followed, will bring them success far

greater than they have alone. It will also

protect them from those who would destroy

them. Although all the captains sign, they

do not pledge loyalty to her or the Code.

They merely watch and wait.

High-ranking and low-ranking sea bandits

test her. She offers those on land a way

to live rather than subsist or starve. In

return, she receives loyalty that is shown

by the vital information they share.

Through blood, ink, and salt (a form of

currency), Shek Ying “becomes the tide

they follow.”

The more powerful they become, the more

others feel threatened. The British, the

Dutch, and the Triads seek illicit trade

alliances involving guns and opium. Such

partnerships will absorb the sea bandits

until they disappear. Shek Ying

understands this and acts to preserve the

confederation and her fellow sea bandits.

When gifts do not bring forth the desired

alliances, their enemies find alternatives

to gain objectives. Spies, saboteurs,

forgers, and traitors work from within,

and Zheng Yi vanishes during a storm. His

loss is grievous, but Shek Ying is

determined to cut out the rot that

threatens to destroy them.

On occasion, I do not explicitly

understand what transpires, but the

significance is always clear. Chapter 55

seems to be a fitting end to the story,

but subsequent chapters are a mix of past

and present, and cover a wide span of

years. In response to my question about

this, Samuel responds:

Once the fleet surrenders,

the book moves away from a purely

chronological progression and becomes

something more reflective – a way of

exploring meaning, memory, and legacy

rather than simply recounting events

in order.

I chose

this structure because it echoes the

way memory actually works: not as a

straight line, but as a series of the

most resonant memories. By placing

scenes out of order – for example,

showing the surrender before the

betrayals that led to it – the story

highlights the hidden personal

struggles behind the official history.

And through these time jumps, we get

to see Shek Ying in her fullness: not

just as a leader at a single point in

time, but as a woman defined by her

choices, her sacrifices, and

ultimately the legend she becomes.

In

essence, the narrative shifts from a

straightforward historical account

into a more poetic reflection on what

remains after everything is over – how

we remember, and what truly endures.

As a result,

readers become immersed in a story in

which fact and fiction are interwoven with

a weaver’s expertise. Although

predominately from Shek Ying’s

perspective, the story occasionally

unfolds from other points of view – a Qing

governor, a pirate captain, a pirate

archivist, a foster son, and a silent

watcher -- to provide a broader picture of

the confederation’s birth, rise, downfall,

and legacy. Key components that flesh out

the story are endurance, greed, and power.

What Samuel deftly shows is that no matter

how often the authorities attempt to erase

Shek Ying from history, she remains as

powerful a figure as she was in the early

19th century. He writes in present tense

and the imagery he wields is vivid. Some

action is subtle; some is not. This is a

pirate tale, just not the one readers

expect. Instead, this passage sums up the

reading experience: “No sirens. No panic.

Only the steady rise of the Pearl River,

slipping under doorways, over thresholds,

until streets carry water like veins carry

blood.”

Review Copyright ©2025 Cindy Vallar

Click to contact me

Background image compliments

of Anke's Graphics |